In several ways, the state of Bosnia and Herzegovina is identical to its western peers. Bosnia has one capital, Sarajevo, served by one Prime Minister, Vjekoslav Bevanda, defended by a singular Armed Forces of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The state, like most others, has one currency (the “convertible mark”) and one top-level domain (.ba).

Bosnia can’t masquerade as a commonplace state for long. Behind the veneer of “parliamentary federalism” is a government system that holds itself together using the very ethnic institutions that divided Bosnians throughout the twentieth century. The country’s vanilla central government divvies its power among ethnic and regional institutions in a system that would stir suspicion in most Americans. The Bosnians have crafted a system of government that, if attempted after America’s own civil war, would have established a dual presidency between the Union and the Confederacy. They have spread power between Bosniaks, Croats, and Serbs in a fashion reminiscent of Lebanon’s “confessionalist” power-sharing agreement between Maronites, Sunnis, and Shi’as. At its highest levels, Bosnia and Herzegovina appears to be a perfectly modern state. But immediately beneath this umbrella is a political system alien to most liberal democracies.

The Fall of the Yugoslav System

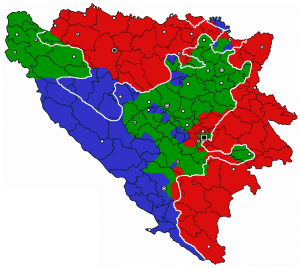

Yugoslavia’s disintegration began relatively quietly. When the Slovenes departed, Slovenia’s relatively homogenous population faced little resistance. Croatia, home to more than just Croats, faced bloodshed in its own struggle for independence from the Serb-dominated Yugoslavia. However, this was peaceful in comparison to the Bosnian War. The Bosnian’s declaration of independence created a messy split between Bosnian independents and those that held loyalty to Yugoslavia’s Serb leader, Slobodan Milosevic. These two groups’ land-grab split the country in two. At the interior, was the Croat and Bosniak-dominated Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Along the country’s norther and eastern borders was the Republika Srpska, an region dominated by Serbs (Boduszynski, 278). The claims left the Federation’s capital, Sarajevo, planted in the middle fo Serb territory. On top of this, the quilted nature of Bosnia’s ethnic geography left countless ethnic enclaves on both sides. Despite the bloodiness resulting from these boundary disputes, the Federation and RS continued to exist as subnational entities when the Bosnian War finally ended.

The Dayton Agreement

Keeping Bosnia’s two warring entities intact into peacetime is itself an interesting political move. The two governments are largely independent of one another. Each entity has its own internal government, complete with law enforcement, a postal service, and (until 2005) an active military. Politicians’ attempts at consolidation have met resistance from Bosnian Serbs, who enjoy a strong majority in the Republika Srpska. Croats and Bosniaks, on the other hand, must split power in order to govern their Federation (Bose, 60). The result of this subnational government is a tenuous peace that has kept wartime divisions alive only because any alternative could provoke renewed violence. If there is one thing the common Bosniak, Croat, and Serb can agree upon, it is that there was enough violence in the 1990s.

As interesting as Bosnia’s political situation is, the ethnic consequences are even more alluring. Negotiators designed the boundary between the Federation and the RS to follow patterns of ethnic settlement. Of Bosnia and Herzegovnia’s three power-sharing presidents, the Serb comes from the Republika, while the Croat and Bosniak leaders come from the Federation. The ethnic separation works – to an extent. The Bosnian ethnic map is like a quilt, with different ethnic populations interspersed amongst each other. Although Srpska is strongly Serb and the Federation mostly Bosniak or Croat, the subnational divisions and split presidency provide only an imperfect solution. The failings of this solution have had unusual consequences. Since 1991, politically motivated ethnic migrations – both coercive and voluntary – have turned Bosnia from a well-mixed ethnic region to an alliance of cultural strongholds. The terms Bosniak, Croat, and Serb have gone from being self-applied ethnic identities to politically-deterministic racial designations.

Despite some claims otherwise, the “ethnic cleansing” policies of the Republika Srpska did have an effect on Bosnia’s ethnic map. The land claims of the RS captured regions mostly inhabited by ethnic Serbs, but also claimed large swaths of traditionally Bosniak territory. As the map at right demonstrates, the Republika’s eastern territories had considerable Bosniak presence. Likewise, pockets of Croat majorities existed to the north of the RS. Under this system, it would be difficult for any one ethnicity to claim stewardship over any given region without significant protest from the other two ethnic groups. In practice, this meant that Serbia could not annex any of Bosnia’s peripheral lands without incurring the wrath of the region’s Croats and Bosniaks.

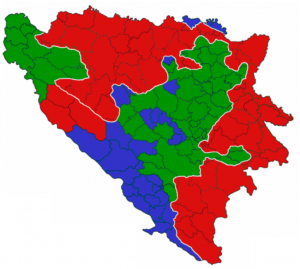

Over the course of the Bosnian War, the Republika Srpska, with the backing of Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic, managed to rid its territory of most Muslim Bosniaks. Regardless of the nationalist Serbs’ methods, the RS was now a largely Serb entity. On the eve of the Dayton Agreement – the event which would formalize Bosnia’s current subnational system of government – the Republika Srpska had only to deal with a Croat region in its western half. The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina contained nearly all of the country’s Croat and Bosniak citizens. With ethnic groups sequestered into cleaner divisions, the tri-presidential system introduced by the Dayton Agreement was a palatable solution to the violence.

Although it was instituted to promote ethnic cooperation, the Dayton system has only further entrenched once-fluid ethnic identities. When terms like “Croat” and “Bosniak” first emerged in Bosnian political dialogue in the nineteenth century, any one Bosnian’s designation was up to his or her family’s own sensibilities (Malcolm, xxi). Generations of intermarriage between the Catholic, Muslim, and Orthodox populations gave many Bosnians adequate claims on multiple labels. An individual’s choice would certainly have effect on his political life (it would be difficult for a self-proclaimed Croat to justify joining a Serb nationalist movement), but few Bosnians could claim any semblance of ethnic “purity.” On top of this, the term “Bosnian Serb” or “Bosnian Croat” could tell you nothing about an individual’s appearance. Genetically, the populations were identical – one would need to rely on observations of custom and worship in order to make a claim to any one Bosnians ethnic identity (Malcolm, xix). But even this would be an imperfect guide: the Bosniak-Croat-Serb division, although close, does not perfectly align with the Muslim-Catholic-Orthodox division.

This all changed with the Dayton Agreement. An individual’s ethnic distinction switched from being an expression of self-identification to a politically-deterministic label. Bosnia would have one Bosniak president, one Croat, and one Serb. The former two could only come from the Federation and the latter from the Republika. Under this system, an aspiring Bosniak politician would have few prospects outside of the Federation, and a Serb in the same situation would have little reason to stray from the Republika Srpska. With the two entities’ boundaries formalized, even those without political aspirations would have reason to flee to their ethnicity’s stronghold. The social capital of Croats and Bosniaks would be much stronger in the Federation than in the RS. A non-Serb family in the Republika could not count on Bosnia’s large Croat and Bosniak populations to look out for its interests, as nearly all non-Serb political influence was in the Federation. By 2005 (the last year the United Nations did a demographic study of Bosnia), the three Bosnian ethnic groups had rearranged to roughly follow the boundaries set by the Dayton Agreement.

Whether by design or by accident, the Dayton Agreement switched Bosnia’s ethnic groups into pseudo-racial identities. When Bosnia’s three constituent groups were forged, an individuals membership was largely an expression of which component of his or her background he or she most identified with. An ethnic identity relied on more than superficial observations, and most Bosnian families had a mixed enough cultural background to make feasible claims to multiple communities. By and large, an identity was not deterministic. With the advent of the Dayton Agreement, however, this fluidity is disappearing. These government-constructed designations act more like racial groups: they are imposed from above, are deterministic, and are (in the process of) malleable only by miscegenation. An individual’s identity is now a formal avenue to accumulate political power, and the longer this paradigm exists the more entrenched familial identities will become. Would a Croat with a Bosniak wife be accepted as a Croat Federation president. Furthermore, what would his son identify as? The homogeneous Republika Srpska may undergo an even more extreme transformation. In another generation, will the the term Bosnian Serb, for the first time in its history, adequately describe a region identity?

The Dayton Agreement has defined the once-fuzzy boundaries between Croats, Serbs, and Bosniaks in Bosnia. It’s too early to draw confident conclusions from this policy, but the de facto segregation under the Dayton system will surely transform Bosnia’s ethnic groups into more rigid identities.

Case Study: Brcko, Bosnia’s Microcosm

If Bosnia is a microcosm of the Balkan Peninsula, then Brcko is a microcosm of Bosnia. The issues faced by Bosnia as a whole are also faced by Brcko, despite the latter being only a small district (see first map for Brcko’s location). Brcko has been richly multiethnic throughout its history (Farrand, 1), so when negotiators wrote the Dayton Accords the small district became a thorn in their side. Brcko did not divide nearly as cleanly as other districts.

Brcko’s solution, just like its problem, roughly mirrored Bosnia. Roles in the district were divided to ensure an ethnic balance (Farrand, 173). Furthermore, international organizations enjoyed a high degree of control over policy in Brcko. The district supervisor’s cabinet was to include representatives from the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the Stabilization Force, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the International Monetary Fund, and the International Police Task Force (Farrand, 6). Like Bosnia, Brcko was designed by outside powers in order to maintain order (Bose, 41).

Census

Bosnians have not filled out a census since the Yugoslavian Census of 1991. Likewise, the modern government of Bosnia and Herzegovina has never issued a census. It is interesting to note, however, that the 1991 census did not explicitly ask questions on ethnicity. Rather, the Yugoslav government collected information on religion, hometown, and “family hometown,” identifiers that could usually help pinpoint a Bosnian’s group identity (1991 Yugoslav Census)

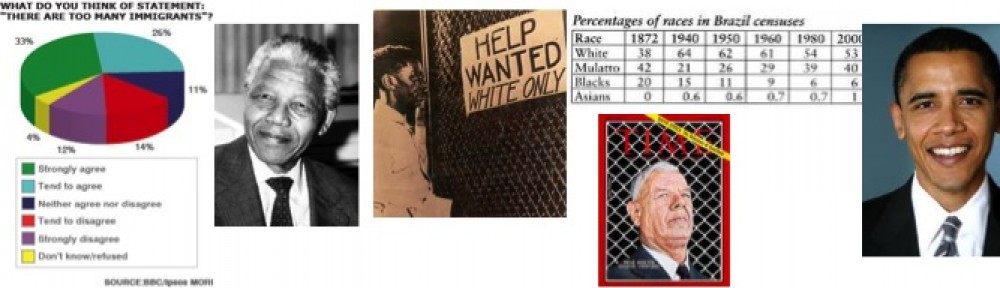

Institutions in Bosnia and Herzegovina – A Comparative Perspective

Bosnia’s institutions are entirely unique among the countries on this website. Canada does not preserve government offices for different races. The French, Turkish, and post-1994 Rwandan governments do not even recognize racial or ethnic groups (Renfro, Baptiste, Song, Institutions). The closest comparison is to the Dominican Republic, which has essentially withdrawn citizenship from Haitian immigrants. Still, the term Bosnian itself does not carry any racial or ethnic identity, so obtaining Bosnian citizenship has little play into the country’s racial institutions.

The most interesting comparison is with South Africa. In 1990s saw the decline of South Africa’s race-based apartheid order and the rise of Bosnia’s Dayton system. Although Bosnia’s political set up does not expressly discriminate against any of the three constituent groups (see Preference Policies), it still preserves offices based on group identity. An imperfect analogy, of course, but it is interesting that Africa, not Europe, appears to be more racially progressive in this comparison – at least where official government policy is concerned.