[Eine kleine Festschriftenfantasieblöggen for Paul Lansky, on the occasion of his retirement]

May 2014. I walk in the door to see eight or ten people I have never met before, gathered around a coffee table covered with neatly stacked piles of paper. I exclaim, “Wow, you guys are hard core!” One man says, “Who is this nice lady? I bet she is a fine soprano.” (Yes, I hope, and no, I lament.) Jay, who until now have I known only aethereally, introduces me to each person by voice type. It is a gaggle, a bevy, of serious singers, many with advanced degrees in fields other than music. We spend hours with Finck, Obrecht, Byrd, and—my favorite, Josquin. We sing his “De Profundis.” One of them. (Is it still his? Let me know.)

Don’t worry; we’ll get to Paul in a moment. There is plenty of time.

The singers debate politely about various translations of German texts and the symbolic significance of hyssop. Judy quotes the opening lines of the Aeneid, in the original and from memory (which I do not understand), and there is an in-joke about Gesualdo (which I do). We sing, “suscipe deprecationem nostram,” and I begin to think of tekka maki. It is the first time I have ever attended a birthday party where I needed my reading glasses. Departing, I say, “I have not done this in thirty years,” but later I realize I have never done this. Ever. I haven’t been this sound-silly since I was last in Cape Breton.

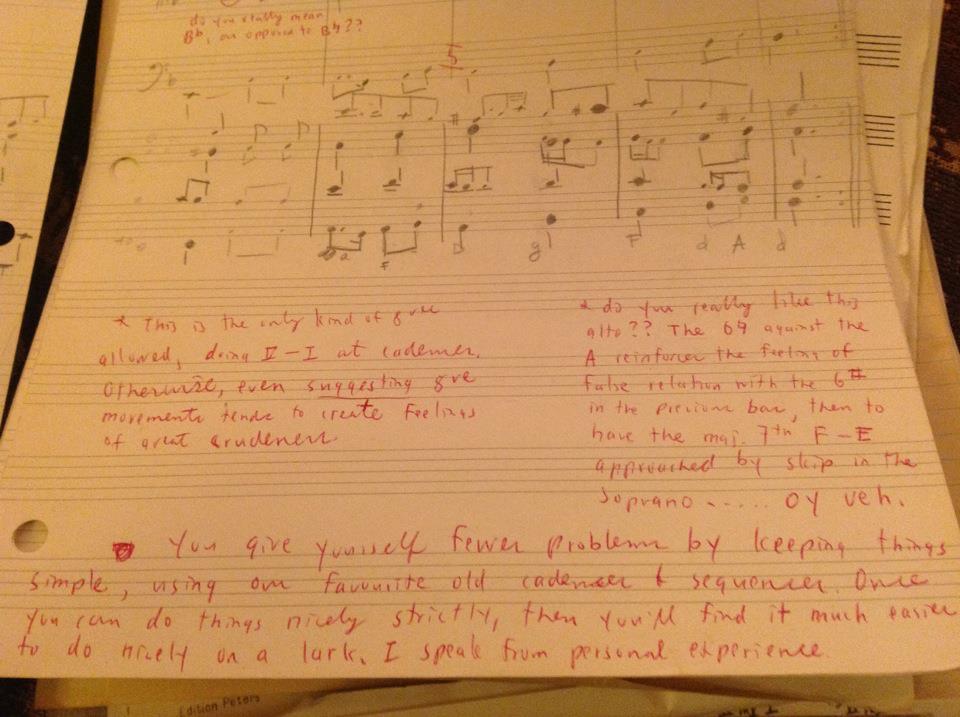

We read from scores made with software John invented; we are unencumbered by unwanted barlines. There are sophisticated discussions about ficta. I hide behind the skirts, metaphorically speaking, of an adept alto and join in when I can. Every flatted note we sing feels like a warm bath.

But still moves delight,

Like clear springs renew’d by flowing.

June 2012. I learn the tune “Frieze Britches,” also known as “Cúnla,” and I marvel at its Mixolydian flavor. I travel from the southern tip of Cape Breton up to the Highlands, and I can’t stop playing it on my tin whistle, except when I grab my shakuhachi to record a second part to “She Moved through the Fair,” to accompany Riley’s recording of the tune he sent me from Kyoto. I send Riley an email with a .mp3 of our disembodied duo attached.

I return to St. Peter’s, my “Frieze Britches” transcription in hand, and a guy says, “Look at that! You can write it down?” “More like, ‘have to,’” I say, in order to keep up and keep my memory straight. (Today on FaceTime™ Charles rummaged around for my transcription, but it was not to be found. It reminded me how inefficient notation is. Eventually I found it in a pile of papers at my own place.)

The flat seven is so marvelous, the way it just tucks itself into the second bar of the tune without incident, radiating warmth. It’s a note with humanity and humility.

“Frieze Britches” reminds me of the first movement of Op. 130, to which (to whom?) Elliot Forbes introduced me in 1983. I don’t think I’ll ever get tired of that F-natural in the cello that brings us from G major into a dalliance with C minor,—and then, whoa!—without warning, everybody slides back into B-flat. (My Lea pocket score from El’s class is far away [in the next room]. . . . Oh, look!—imslp has the first edition!)

It’s like a filmic dissolve, a maneuver Paul and I both recognized in Dichterliebe one day in the Cone Room. (—“Meanwhile, back in the disillusioned and lonely present . . .”)

Already in the downbeat of m. 9, after a few elevated and pointy G-sharps, the bass lumbers down to the subtonic, deflating any hope one could possibly take from an excited heart.

These dull notes we sing

Discords need for helps to grace them;

Spring 2006. At Lincoln Center, I sit next to Paul for a performance of Eliot Feld’s Backchat, which he choreographed for Mandance using Paul’s Idle Chatter Junior. It is so different from anything I would ever think to do, stunning in a way that makes my eye and ear both work new muscles. The dancers all face the back and engage with a wall upstage. There is something about the fixity of the recorded sound and the property line enforced by the wall, as well as the men facing away, that suggests a mysterious and allusive sort of vertical boundary, and the photographic quality of the music makes the visual, too, seem like a picture—a moving one. Later we chat in the lobby about the way music touches choreography, and Paul says that it is less like counterpoint of two voices than like a sort of multiplication. I have just published an article that says exactly that, and I think, perhaps I did not need to go to all that trouble of writing it down.

After intermission, back in our seats with Hannah, Paul and I discuss some department lore, and he says, “I’ll tell you that story sometime.” Maybe I’ll hear that one on Tuesday.

Somehow we get on to functional harmony and modulation—à propos of what, I forget—and Paul says, “Fuck the dominant. I like the flat side.” (I wonder whether I need to bleep, or bloop, or -F-, the F-word? It’s a quotation, though . . .)

What is it about the flat side? The same year as that conversation, I was attending Susanna’s tai ji class. Paul had told me about her years earlier, and I think he said Hannah learned the sword form. (Did their young sons go too? I think so.) It’s as if the emphatic, bright, five, the yang, causes the four to seem even more itself, more steady. This stable, imperturbable yin has no need to hit you over the head to show its strength. (I remember what happened when my boy dog was joined by a new younger female: she played alpha, and he just sat around and snorted as if he could not be bothered.)

Four, five: could we have one without the other? Could it be that the harmony that can be harmonized is not the true harmony?

Ever perfect, ever in them-

Selves eternal.

That same month as the Lincoln Center performance, Lisa sits for her General Exam and tells us some things we don’t know about the different versions of Petrushka. We all vow to save the handouts. I still have mine. In the course of the exam, which also concerns Stravinsky and Balanchine’s Agon and Orpheus, as well as the theme of “memory in music,” Paul has occasion to ask Lisa about gender in music. (In one of the ballets? I am not sure.) He turns to me, and since it is Lisa’s exam, I ask, “Why do you ask?” Paul replies, “Well, you’re the gender.” I’m told this Lacanian exchange is still talked about among the graduate students. (Well, I was told that, back then.) Later, Lisa writes about Antony and the Johnsons, relying on recent and sophisticated theory of transgender (and other) identity. So, now Paul and I can ask students about transgender matters too. (Way back when, Walter was described as having a “sex change.” More recently this has been called “sex reassignment surgery.” Just recently I heard the term “sex affirmation surgery,” which sounds so much nicer. It’s fascinating how things change.)

Rose-cheek’d Laura, come,

Sing thou smoothly with thy beauty’s

1985. It’s Killian Hall, I think. (Can someone remind me?) In those days, such concerts formed the electric ghetto within the new-music ghetto; but back then we (we?) felt happy to be off the menu, misunderstood. And (parenthetical) redfish were nowhere on the horizon. This is before MIDI, before the laptop, and before the return of the turntable. The posters advertising “electronic music” attract the usual group of Cambridge/Boston eggheads. We ride our bicycles to M.I.T. and leave our right pants legs bound through the evening (why not?). Soon the DX7 will make itself available for us to eschew. We furrow our brows in consternation and discuss the intricacies of FM synthesis and the LPC we are all waiting to try. (Actually, I won’t learn about all that until the following year.)

I find this proudly esoteric brain-collective enticing and exciting. Occasionally, one or two “outsiders” show up, expecting something else from the term “electronic music,”—Tomita? Walter/Wendy? “The Popcorn Song?*”—and they usually start to giggle when the bleeps and bloops start, as if it’s the rest of us who don’t understand. Perhaps they’ll turn out to be right. Meantime, I like thinking that I am in the know and that they are unsophisticated: they are outsiders to the outsiders. This music is reserved for just a few of us.

Back to Killian Hall. Who is this Paul Lansky? “As If” begins. It sounds as if the string trio is tuning up. The sounds relate to something I have heard before, something I hear at all the other concerts I go to, except these electronic ones, since the speakers are already calibrated. (Except there was that concert where the piano was a quarter-tone away from the tape and we had to wait for them to be brought into agreement. This made Miller chuckle. Which one adapted?) For the “tape pieces,” an obsolete term we hang onto sentimentally, the house lights go down, and each twin speaker gets a spot. This is romantically austere, but some prefer to include “real” musicians in order to liven things up. (Many years later, Eric will note how many pieces from those days were composed at quarter note = 60, since we were thinking in seconds—that is, durational seconds.)

Soon after, I go to Briggs and Briggs (R.I.P.) to buy the album Computer Directions, which pairs Paul Lansky’s Six Fantasies on a Poem of Thomas Campion with James Dashow’s Second Voyage. I hear the Fantasies (and Campion’s poem) for the first time, and I am stilled. It gives birth to an ear-what? It’s not a worm, because this is good. An ear-worm is when someone says they want a Coke™ and my inner voice starts to teach the world to sing, or when I meet someone named Laura and get distracted by the theme from Preminger’s film starring Gene Tierney. I hear someone say, “Don’t worry,” and depending on the inflection, I may or may not hear Bobby McFerrin rev up. Paul’s Campion, though, creates something more like a blossom, but I cannot call it an earbud, can I? Perhaps an ear-gem. It stays in my memory and imagination over twenty-eight years, so far. I still have the LP (actually, I am afraid not), and I am still, now, listening to it for the first time. I’m not sure I even need to hear it from outside my own imagination. Sometimes I worry about experiencing for a second time things I have been so taken with on first meeting: it’s Mark Epstein’s Lobster Roll Phenomenon. Like ordering Shahi Paneer in Allston, being overwhelmed with contentment, and never quite finding the same masala again. Or a flavorful red wine that enthralls at first, but later merely pleases. Six Fantasies, however, has no such problem; inside or out, then and now, its sheen and richness, its elegance and grace, resound.

Six Fantasies sounded entirely different from those dispersive, confounding pieces I loved to listen to (and perform, and compose). I don’t think those uninitiated spectators would have giggled at Paul’s Campion. It was unlike anything I had ever heard, new or old, electronic or acoustic. It began with a rich yet digestible D, gleaming, sounding a bit like a horn, Paul’s instrument. Ooh, there’s the flat seven above: it seems to open up the airspace for a bionic woman’s voice to travel through, and she names, simply but sublimely, “Laura.” The sounds go deep, but some come closer, and some lay back. How can this “fixed” music have so many dimensions? There is the horizontal trajectory of the poem, its setting, and its variations; the vertical window of the seventh and its transformations; and the perspective extending all the way from here to there and articulating all the places in between.

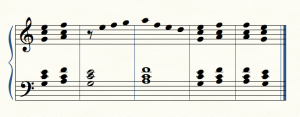

At any point in my life, I can exorcise “It’s the Real Thing” by thinking of this synthesis of “her song”:

Of course, this is not how it goes. But I remember those first two words, those four notes, and I cannot possibly forget what comes next. You’ll have to check it out for yourself though: it’s Paul’s.

It seems both impossible and perfect. How did he think of that? And had he not, what else could possibly have gone there?

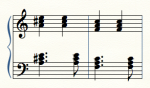

Again, there is something I recognize, though I would not dream of calling it the “I Got Rhythm” set. It’s one of my own favorite patterns, though I prefer the inversion. And when he gets to the gritty part, “her ritual,” it seems to make sense for it to be fragmented, filtered (is that right?), percussed, grained—groaned and moaned. The Fantasies do not start here, inside a ruin, though; instead they grow and decay, so I know how they have arisen and descended from something I used to know. There’s something that has been broken down, so you can listen backward and remember what it was once was.

Lovely forms do flow

From concent divinely framed;

The speaking gradually emerges, becoming itself, undressing, so that in the final fantasy—so to speak—I hear at last the unadorned, unfettered voice. I wonder, who is this Hannah MacKay, who is reading the poem and whose speech is being transfigured into these fantasies? (I’ll find out in 1998 and will talk to her about her studies in classics. But first, in 1987, I will sit in Betsy Jolas’s seminar at the Conservatoire, and one of her most insightful students will describe Debussy’s etude “Pour les sonorités opposées” [no copyright infringement intended] as music that comes closer and recedes, rather than propelling one forward in time. That seems about right.)

Only a year later will Barry teach me Music 11. A veteran will warn, “Just you wait for the digital filters lecture. . . .” Leaving that lecture and all the others, I will ride back up Mass Ave., right pants leg bound, camping-size backpack attached, back to Harvard Square to serve as waitron (I am not making this up)—at Souper (ditto) Salad. Bob Lobel is a frequent customer.

The year after that, Ivan will initiate me into the wonders of reel-to-reel and a blade, then the Serge, then the Moog. Each student will complete a realization of Douglas Leedy’s Entropical Paradise, and Ivan will assign us readings from William Burroughs, alongside an alchemy textbook. Twenty-six or so years later, I will run into Mark Janello, or his avatar, again. (Yes, I am moving backward in time.) I remember asking Ivan whether he thought my disassembly of Lester Young and Billie Holiday had too much of an air of “musica reservata” about it, and he said no, he liked that aspect.

Back in 1985, I study Six Fantasies on a Poem of Thomas Campion in Peter Lieberson’s class, and without any particular rationale or even a trumped-up excuse, I write to this Professor Paul Lansky at Princeton. I figured that when you study people’s music, you talk to them about it. (Maybe it is a girl thing; they say we like to converse.) I had to look him up in that old directory of college music departments, and, within a week, in what we then called simply “mail”—no gastropodular modifier was necessary, though at M.I.T. we did send aethereal communications back and forth, again feeling exhilaratingly disembodied—Paul sends me a nice note, enclosing “a couple of pages from Charles Dodge’s book,” Computer Music: Synthesis, Composition, and Performance, which was not yet published. (Any Resemblance Is Purely Coincidental will turn out to be another piece that has something identifiable about it.)

Another few years later, I have a friend in the graduate program at Princeton, and he ushers me into Woolworth, where we peek in the door to gaze at the legendary NeXT computers. (It’s before the renovations, but I later realize it’s the same room where the graduate students—actually, what do they do in there now?) I spy Paul in the corner, working with a student, and I think, “Wow, that’s the real Paul Lansky—the one whose record I have. He sent me those pages from Charles Dodge’s book.” Of course, I would never have dreamed of saying hello. Before we do finally meet, in 1998, Mathew informs me that Paul has a new CD out. I zip over to Audio Options to pick up Things She Carried. There’s Hannah again, and she is speaking in a more everyday manner now, describing “a comb with several teeth missing,” “five credit cards,” and a “Social Security card.”

Paul’s is music of relationship: things meet up and talk to one another, whether remotely or face to face, whether, as he says, silicon or protein. There is specialness made out of ordinary things: shiny pots and pans, distant casual conversation, even a reading of the utilitarian alphabet, and even the too-familiar sounds of the highway. (This one says “I do not own any right.” What about this one?” Accidentally, I just let them play at the same time, a bit out of sync. The colliding highways sounded pretty great.) And there is the music of music: Andalusian-inspired piano filigree, the Baroque suite, and even a fragment of Isolde (whose modified form will be famously mutated by a few members of a younger generation).

These are all his.

I migrate to Paul’s schoolyard, and I hear the clock tick as a dancer explores the floor. (There’s also the bunny with the vacuum cleaner. I have scoured with Google™, and it seems to be the only thing missing from the Internet. I found Grady’s video imagery inescapably gynophobic . . . but that’s a different story.) And later, music for horn, piano, percussion,—the kind that needs people to get on stage for us to hear it. There are even, despite what even he might have predicted, songs:

I thought I’d write a song or two, so I tried, and tried again. It seemed like a perfectly natural thing for a young composer to do. Everyone else was doing it, so why couldn’t I? But nothing worked, it felt wrong, it sounded bad, awkward, self-conscious, pretentious, even ugly.

(It’s fascinating how things change.)

Paul often proposes,“let’s burn that bridge when we come to it.” Or when I ask how he’s doing, he’ll say, “I’ve been worse.” Last week, as he graduated from the ritual of administering graduate exams with the rest of the composition faculty, I finally dared to ask if I knew him well enough to inquire as to what he means when he asks students about orchestration in piano music. He remembers my old silvertone email address and occasionally calls me babz.

1998. Paul suggests that I serve as Mary’s dissertation advisor and adds, “I hope you don’t think I’m just sending all the women students to you.” I say that’s good to know, but I might not mind if he did; there is research that suggests same-sex mentorship to be of great value.

May 2014. We lost Mary to cancer thirteen days ago.

Only beauty purely loving

Knows no discord,

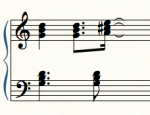

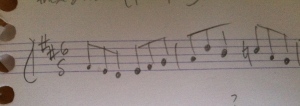

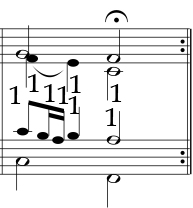

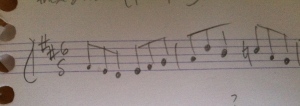

1985. In music history class, I learn about Josquin and become addicted to his Missa Fortuna Desperata. (Is it still his? Let me know.) Like Paul’s Fantasies, the Agnus Dei is something I can conjure up without hesitation—not the piece itself, but specifically the Boston Camerata recording. There’s this intoxicating, addicting riff, on the first syllable of “mundi”:

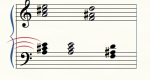

It seems Josquin was drunk on this too, for he swims around in it for a while. A bit later, we hear the second syllable, and an inner voice sings:

I can’t imagine a more beguiling leap of a fourth. But of course, this is not the music. It’s more magical than that. (Paul once asked me whether I ever cast spells, but that too is a different conversation. [I don’t.]) It’s a stunning homophonic moment, where the voices join together, a congregation of mortals addressing the one who “takes away the sins of the world.” Check it out and see where it goes next. (“Miserere” is the text, so I’ll leave that aside for now, since this is a celebratory occasion.)

Heav’n is music, and thy beauty’s

Birth is heavenly.

(When he heard my “Sin,” a memorial to my mother that fantasizes on the old song Tain’t No Sin, Paul told me about some then-new-for-me things he heard. One was “anger.” He was right. I was touched that he noticed. A couple of years later, he delivered a compliment, something about sneaking up on a groove, or something like that. I hadn’t thought of it that way. Even later I visited his “pitch freak” seminar, and it seemed we both liked to maintain a distinction between white and black notes [transpositions allowed].)

Having had my first splash with Josquin last week—well, it was more like treading water—I thirst to sing this Mass, to hear the sweet discords and divine graces fill up the space between and around a circle of voices. (I’ll just send this hint out into the aether and see if anyone notices . . . )

A few years ago I caught the Boston Camerata recording of the Missa Fortuna Desperata on the radio. I put it on in two rooms, one the “real” radio and one streaming, and as I walked between rooms, I noticed they were a couple of beats apart. Another kind of swim. This week I looked on the Internet for the Boston Camerata recording. It has not been re-released?! How can that be? I listen to the Tallis Scholars, but their recording just will not do. Fortunately, this one is one of the LPs I have kept on hand. (This is true.) I ask Dan and Darwin to help, and Dan digitizes it for me in a flash. He says he’ll have a scan of the score for me next week. I have the .ra files, but I hesitate to listen to it. The memory is so good already.

Silent music, either other

Sweetly gracing.

I’m not sure I’ve kept my tenses straight, but then, that tends to happen when there is so much to remember. So many gems and fancies to discover, hold, gather, drink in again, and cherish. So, this has gotten sort of long. But then, so has our association, and Paul’s works list even more so.

Congratulations on your graduation, Paul. I’ll see you Tuesday for sushi. Please let me treat this time.

[Quotations are from Thomas Campion’s “Rose-Cheek’d Laura” and from Paul Lansky’s “I Thought I’d Write a Song or Two.”]