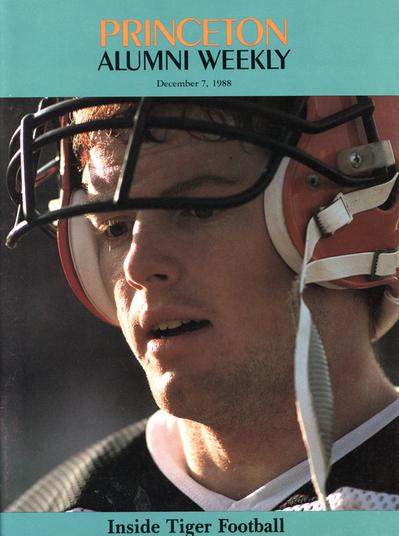

How big of a star was Jason Garrett ’89 in his Princeton days? Well, big enough to land on the cover of the Princeton Alumni Weekly. Garrett, officially named head coach of the Dallas Cowboys Jan. 6, was a focal point of “A Season in Seven Days,” which offered an in-depth look at the week leading up to the Princeton-Yale game in his senior year.

Led by Garrett’s sharp passing, the Tigers beat the Elis in New Haven for the first time in more than two decades. Garrett won the Bushnell Cup as the Ivy League’s most valuable player, but Princeton fell short of an Ivy title. A year later, brother Judd Garrett ’90, a star running back, would lead the Tigers to a championship.

Below, read more about Jason Garrett and his teammates from the 1988 team.

From PAW, Dec. 7, 1988

A Season in Seven Days

By David Williamson ’84

Sunday, November 6

FOR A FEW anxious moments late one recent Saturday afternoon, Princeton’s head football coach, Steve Tosches, saw his worst nightmare come true. His Tigers had a three-touchdown lead over Colgate when Princeton’s star quarterback, Jason Garrett ’89, scrambled around left end on a broken play. In similar straits in the first quarter, Garrett had slipped over to the left sideline and scampered for a sixty-one-yard gain. This time, he turned upfield and was promptly hammered by the Colgate safety. Garrett crumpled to the ground and didn’t get up.

On the Princeton bench, the players and coaches fell silent. Garrett was the team captain and had been the quarterback on every offensive down during the season, so the Tigers would miss him badly if he were seriously injured. Finally, Jason staggered to his feet, weaving like a punch-drunk boxer. The field judge called over to Tosches: “Hey coach, you gotta get him out of here. He got his bell rung pretty good.”

By the time Garrett reached the bench, he was insisting that he was fine, even if he was still a little woozy. “It was a stupid play on my part,” he said later. “I should have slid under the tackle.” Brian Barren ’89, the backup quarterback, replaced Garrett, and the Princeton offense promptly scored on its next drive to push its lead to four touchdowns.

Twenty-four hours later, in an office in Jadwin Gym, Coach Tosches sat in the flickering light of a sixteen-millimeter film projector and winced again as he watched the slow-motion replay of Garrett getting clobbered. He rewound the film and started it forward again from the snap of the ball. This time, he concentrated on the block thrown by Kevin Coupe ’89, the right guard. “Coupe and this kid look like a couple of rams locking horns,” Tosches said. Craig Cason, the offensive line coach, nodded in agreement. “That’s a nice block,” he said. “Coupe did a nice job this week.”

It was early Sunday afternoon, and Tosches and his offensive staff were dissecting Princeton’s 45-13 thrashing of Colgate. In an adjacent room, the defensive coordinator, Bob Depew, and the team’s three defensive coaches were analyzing the play of the Tiger defense. Each week during the season, these Sunday meetings mark the beginning of a new cycle for the Princeton football program-one that ends seven days later with a game. This week, the opponent at the end of the cycle was Yale. Preparing for the Elis would place demands not only on the nine coaches and one hundred players, but also on the dozens of trainers, equipment managers, alumni boosters, and others who help to keep the program running. Even in the Ivy League, college football has become a major production.

On this particular Sunday, Tosches had a lot more film to watch than Depew, and that made everybody happy. In the course of piling up 459 yards of offense against Colgate, Princeton had run more than eighty offensive plays and had held the ball for forty-one of the game’s sixty minutes. The defense had surrendered a touchdown on the first drive of the game, but thereafter it had throttled the Colgate offense, holding the Red Raiders to fifty-eight plays.

Listening to the coaches talk in the darkened projection room, however, one would never have thought that the Tigers had won by thirty-two points. Tosches watched a junior lineman miss a blocking assignment and said, “I sure hope that’s not a preview of coming attractions.” Later, Cason despaired of the footwork of George Sarcevich ’89, the starting left tackle. Shaking his head, Cason lamented, “George, George, no, George, not like that.” But Tosches grinned when he saw the replay of a clutch, third-and-long run by Dennis Heidt ’89, the fullback. Suspecting that Colgate would blitz its linebackers on a third-and-long play, Tosches had called a draw. The linebackers had indeed come after Jason Garrett, and Heidt had burst through the middle for thirty-five yards. “Sometimes you guess right,” Tosches said.

At three o’clock, the entire coaching staff assembled in a third-floor conference room in Jadwin. By now, everyone had seen the Colgate game two or three times. Tosches asked Depew about the team’s defensive performance. “No problem, Steve,” Depew said. “We would have held them to under 100 yards total offense if we could have contained their quarterback a little better.”

After all Princeton victories, the coaches award a game ball to one of the seniors on the team, and this week they decided on David Wix, a split end who had caught ten passes for 132 yards. The coaches then discussed the other weekly awards. “For Offensive Player of the Game, it’s got to be Jason, right?” Tosches asked, looking up. “What was he, 23-for-29? Another day in the office.” The defensive coaches gave the Defensive Player of the Game honor to the strong safety, Greg Burton ’90, a converted running back who recorded eight tackles, a sack, and an interception.

By five o’clock, the players had crowded into the locker room for their weekly Sunday meeting. At the stroke of five, Tosches stepped into the room and closed the locker-room door behind him. The assistant coaches and I sneaked into the darkened room next door, and listened through the connecting door at the back.

Only thirty-two and in his second season as head coach, Tosches still looks more like an altar boy than Knute Rockne, but the players shut up immediately when he closed the door. He congratulated them on their victory over Colgate and handed out the game awards. Chris Lutz ’91, the kicker, got an especially big hand when Tosches announced that he had broken the Princeton record for successful field goals in a season. The old record, sixteen, had been set in 1965 by Charlie Gogolak ’66. “Nothing against Chris, but half of those field goals should have been touchdowns,” Tosches grumbled later.

The team then divided into smaller groups to watch the film. I followed the defensive backs and linebackers down into the basement of the Caldwell Field House and into the clutches of Coaches Steve Verbit and Mark Harriman. I wanted to watch a replay of the best tackle I’d seen all year, a punishing upper-body shot that the middle linebacker, Franco Pagnanelli ’90, had inflicted on an unsuspecting split end. Moments later, Pagnanelli had flattened another Colgate receiver, who was foolish enough to venture over the middle. When Pagnanelli’s tackles were replayed, they drew whoops and applause from his teammates, and Coach Verbit obligingly ran the film back and forth several times so that everyone could admire Franco’s fine technique. Then it was back to business: “Get width, you’ve got to get width,” Verbit intoned. “Frank Leal [’90], you’ve got good width here; strengthen the boundary.” To the linebackers, Harriman was barking instructions with the clipped cadence of a Parris Island drill sergeant, too fast for me to follow. Later, I whispered to Verbit: “What do you mean, ‘get width’?” “You know,” he shrugged. “Get wide. On the field.” He paused. “You want to keep the other guy from getting to the outside, so you go wide and force him back to the middle, where the rest of the defense is.”

At six-thirty, the players headed off for dinner in the cafeteria atop the New South Building, where the team eats its evening meals during the season. Most of the coaches went home, and so did I. Later, I learned that the part-time assistants – Steve “Digger” DiGregorio, Rick Ulrich, and Gavin Colliton – spent another couple of hours collating film of Yale.

Monday, November 7

I STRAGGLED into Tosches’s office at twenty minutes to seven in the morning. The scene seemed like an instant replay of the previous afternoon: the offensive coaches huddled around a projector in Tosches’s office. They were watching grainy black-and white film of Yale’s wins over Dartmouth and Columbia and its loss to Penn. (According to Ivy League protocol, opponents trade footage of their preceding three games.) For good measure, the staff had unearthed footage of last year’s embarrassing 39-13 loss to Yale in Palmer Stadium.

“Look at the nose tackle,” Mike Hodgson, the receivers’ coach, was saying. “They’re kicking his ass ten yards downfield on every play.” Cason laughed, and said, “That’s what we saw on film last year, and look whose ass got kicked.” Tosches interrupted. “Are they playing out-on?” he asked, peering at the screen. “We might want to go back to the tight end circle.” Against Colgate, the Tigers had successfully exploited the halfback circle, a delay pass to Judd Garrett ‘90 coming out of the backfield. Yale would concentrate on stopping Judd, Tosches reasoned, so why not let tight end Mark Rockefeller ’89 run the circle pattern instead?

By lunchtime, the coaches had plowed through four entire games, and they were beginning to develop a good feel for Yale’s defensive philosophy. “We play the percentages and look for tendencies,” Tosches explained. “By this point in the season, it’s pretty clear to us what those tendencies are. Every week, someone tries to show us a new wrinkle, but that’s mostly window dressing.”

The percentages that Tosches was talking about are calculated by an I.B.M. personal computer, using a complex software package that was devised by Kevin Guthrie ’84, a record-setting Princeton receiver. Guthrie’s program can rapidly sort through the data from several football games – all the plays, formations, defenses, and so forth – and accurately chart a team’s tendencies in any given situation. Assistant coaches can do the same thing, but the computer does the job much faster. Among Guthrie’s clients are the New York Jets and collegiate powers Alabama and Nebraska.

At big-time football schools, which employ dozens of assistants, Guthrie’s software can save many hours of tedious labor. At Princeton, where Ivy rules limit the staff to six full-time and three part-time coaches, it has even more potential. But according to Tosches, the Tigers have only been able to use the system to about half of its capacity this year. “We got the computer after the season started, so we’ve never really had a chance to figure out everything that it can do,” he said. “That’s something to explore over the winter.”

By three in the afternoon, the coaches had agreed on the rudiments of their game plan for Yale. The film had revealed that the Eli linebackers blitzed a lot; Princeton would counter with a package of quick pass plays, designed to get Jason Garrett to the outside and away from the teeth of the Yale pass rush. “They’re giving up the short pass,” Tosches concluded. “We’ll have the seventies all afternoon.” In the Princeton playbook, short, quick pass patterns are labeled the “70” series, and they were among the first plays the Tiger quarterbacks ran when practice started two hours later.

Varsity football practice follows the same routine, Monday through Thursday. From 4: IS to 4:45 every afternoon, the players watch film and listen to the coaches. Then, out under the lights on Frelinghuysen Field, Jason leads the team in fifteen minutes of stretching exercises. The team next splits into different units for specialty drills-running backs take handoffs, receivers run pass patterns, and linemen slam into blocking sleds. Usually, practice ends after a controlled contact scrimmage between the starting elevens and the scrubs, and by half-past six, the players are heading back to the locker room.

Tuesday, November 8

FOR THE coaching staff, Tuesday morning meant another marathon session with the films of Yale. I skipped the dawn showing, preferring to attend a private matinee with Bob Depew. He was sitting alone in his office next to a projector, a pile of unwound film at his feet like so much celluloid spaghetti. “I never got a pickup reel for the projector,” he explained sheepishly. When Tosches assumed command last fall, he gave Depew a free rein over the defense, and this arrangement is still in effect. During games, Depew sits in the press box, calling defensive formations and advising Tosches and the other sideline coaches over a two-way headset.

“Our ends are going to have to play well if we’re going to stop Yale,” he said. “They run the same kind of option play that gave us trouble against Brown and Penn.” I asked if the defensive line was up to the task. “Ask me at five on Saturday afternoon,” he said.

Next door, the offensive coaches were talking about such mysteries as the “waggle,” the “Pro-I 144 Sprint Pass,” and “throwing dig to field,” so I called on Dick Malacrea, Princeton’s head athletic trainer and proprietor of what the players call “the House of Pain.” Malacrea was just starting to tape the left knee of Kevin Lynch ’89, a defensive tackle. Three other trainers and a doctor work in the training room, but only Malacrea tapes knees, and watching him apply one of his custom wraps is like watching an expert barber flourish a straight-edged razor.

First, Malacrea builds a foundation for the tape with a layer of short pieces of sticky elastic bandage; for the back of the knee, there are several pieces of foam under the elastic. He then applies the stiff white tape that actually provides support, and when he’s finished, all that’s visible of the player’s knee is a crunched-up peek of patella. Every day during the season, Malacrea performs this precise five-minute operation on every injured knee on the team.

I asked him how many miles of tape he had used in his twenty-one-year career at Princeton. “Everybody always asks me that same stupid question,” he said, laughing. “I don’t know. What difference does it make?” He put the finishing touches on Lynch’s knee, gave him a slap, and called out, “Next!” Next turned out to be Ray Ryan ’89, a linebacker who had torn the medial ligament in his left knee a month earlier. After sitting out several games, he had played against Colgate. He stood up on one of the training tables and offered his freshly shaved leg to Malacrea. (The players all shave to mitigate the agony of removing hair along with athletic tape.)

Malacrea selected a new roll of elastic bandage, and told me that Ryan was about “90 to 95 percent recovered” from the injury. “In most cases, they have to be at 90 percent before it’s safe for them to play,” he said. To determine this percentage for leg injuries like Ryan’s, Malacrea employs a sinister-looking machine called the Cybex II. This union of high tech and Torquemada comes with straps and buckles, twenty-six accessories (labeled “A” to “Z”), and a built-in computer that measures strength, endurance, and flexibility. As an athlete exercises, the computer spews out a graphic record of his performance, much as the vital signs of patients undergoing surgery are monitored. The resulting graph allows Malacrea to compare the performance of an athlete’s healthy limb with that of the injured one.

Across the room, Chris Hallihan ’91, a fullback, was undergoing a session with a twentieth-century version of the rack. Malacrea called it “intermittent cervical traction,” but it looked to me as though Hallihan’s head were a giant yo-yo, bouncing up and down on a length of wire. “I jammed my neck,” he gasped. His head was cradled in a canvas sling that dangled from a steel cable. The cable, in turn, snaked up into the traction machine. This device (also made by Cybex) applied thirty-five pounds of upward pressure on Hallihan’s neck every few seconds, and then eased back. Hallihan would be in big trouble if the machine decided to reel in the cable all the way.

A half-hour before practice, the training room was crowded. A number of the players were there just to soak sore feet, hands, or legs in one of the Ille whirlpools; others sought out heating pads or Ultrasound treatment for sore back muscles. The Tigers’ walking wounded seemed afflicted with every possible football-related injury save one-sprained ankles. Three years ago, Malacrea mandated that all players with a history of ankle trouble wear lightweight ankle braces. Since then, only two players have suffered sprained ankles while wearing them, and as it turned out, one of these was wearing the brace improperly.

Missing from the training room was the rich smell of liniment that one normally associates with athletic injury. Bill Cullen, the team’s physician, told me that no one uses the aromatic stuff anymore. “Ibuprofen – Advil or something like that – that’s the liniment of the eighties,” he said.

Wednesday, November 9

AT TEN IN the morning, equipment manager Hank Towns started packing the big 3’x5’ lockers that the team takes with it on the road. “Usually, I don’t do this until Thursday, but we’ve got a lot of other teams with games this weekend,” he said. Towns is responsible for purchasing and maintaining the thousands of different pieces of athletic gear the university owns, from racing shells and fencing mats to football jerseys and shoulderpads. During the football season, however, both Towns and his alter ego, Cap Crossland, work pretty much full-time with the football team, doing everything from laundering jockstraps to fixing helmets.

In the next room, Crossland and Gary Mosley were scraping mud off the varsity’s white Converse game shoes. Towns’s nineteen-year-old son Mark took the cleaned cleats and lathered them with Hyde Deluxe Professional White Shoe Polish. “They look real sharp, don’t they?” Crossland remarked. A seventeen-year veteran of the equipment staff, Crossland came to Princeton only a couple of months after Towns, and together they preside over enough gear to stock a big sporting goods store. On the walls of their windowless lair, autographed photos of former Tiger captains compete for space with posters of the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders, the Raiderettes, and Florence Griffith-Joyner.

I asked Towns how much it costs to outfit a football player. “Well, the helmet’s $95 to $125,” he said. “Then you’ve got to add the cost of the face mask, depending on whether you want two-bar or three-bar, open or closed. Shoulderpads, they can cost up to $300, and shoes, you’re looking at another $70.” He reeled off everything else: pants, socks, jerseys, undershirts, shorts, supporters, ankle and knee braces, mouthguards, gloves, elbow pads-a minimum of $500 of gear for each of the hundred players on the varsity team. “Actually, the hockey guys cost more on a per-player basis,” Towns said. “Some of those guys go through fifteen, twenty dozen sticks during a season. That adds up.”

Crossland headed upstairs to inspect the helmets for damage. In particular, he explained, he was looking for cracks or dents in the plastic face masks. “If the face mask isn’t on good and tight, then the rest of the helmet won’t fit,” he said. He pulled down a helmet from a lineman’s locker and held it out. “See?” he said. “This guy gets hit every play, and his mask is loose.” Crossland carefully tightened the nuts that held down the mask. “When he comes in, we’ll check the air.” Crossland pulled back the black stripe down the center of the helmet, revealing three small holes. “See? Put a needle in there, and then you can pump up the air bags inside to fit the kid’s head,” he said.

Towns and Crossland constantly experiment with new equipment, using volunteers from the team as guinea pigs. “They’ll try something in practice, and tell me how it feels,” Towns said. “If it works out real well, like the ankle braces, then we’ll give them to everyone.” Riddell helmets and shoulderpads are the standard varsity issue, but some players find other brands either more comfortable or more glamorous. The meanest-looking, most-desirable shoulderpads in the locker room are the so-called “PowerPads.” Made of dark gray high-impact plastic and gray foam, they look like props from a science fiction movie. “The more straps and gadgets, the more the guys like it,” Crossland observed. “Some of them put on so much gear that they have a pad on every inch of their bodies, from their neck down.”

Later that afternoon at practice, the regular core of sideline spectators assembled: assistant trainer Johnny Pelego, Dr. Cullen, nine-year-old team mascot Arthur Gross, and manager Katherine “K-T” Graves ’89. They were joined by a stout, balding man who was smoking a cigar the size of Havana. He introduced himself as Somers Steelman ’54, the chairman of the Friends of Princeton Football. “I try to get out here a couple of times a week to let the guys know that the alumni are behind them,” he said. “Here, have a lapel pin.”

Like the powerful booster organizations at many Division I-A schools, the Friends of Princeton Football raises money for the football program and helps with recruiting. Unlike some of the big-time booster clubs, though, the Friends doesn’t entice star recruits with sports cars or promises of a full athletic scholarship. “Hell, we can’t even guarantee that they’ll get in, to say nothing of giving them a free ride,” Steelman said. “Schools like Stanford and Duke are going after the same pool of recruits that we are, but they’re offering full scholarships. How are we supposed to compete with that?”

Even so, the Friends of Football is the biggest and best-financed of Princeton’s alumni booster clubs, and its members underwrite a number of football-related expenses. The group provides airline tickets for recruits who cannot afford to visit the campus – the Ivy League forbids universities from using their own funds for such trips – and also pays for the high-quality food that is served at the training table. (“These guys burn a lot of calories,” Steelman said.) Every year, the Friends of Football sponsors a “career night” for the seniors on the team, and three years ago, the group raised more than $1.5 million to endow the head coaching position. The university, however, picks up the majority of the football team’s costs, including travel, equipment, and salaries. “We just fill in around the edges,” Steelman said.

Steelman was still puffing on the same cigar when practice ended. While the players knocked mud out of their cleats, he circulated among them, offering encouraging words. “Before a lot of these kids came to Princeton, I was in their living rooms, talking to them and their parents about college,” he said. “It’s nice to watch them go through.”

Thursday, November 10

WITH THE game against Yale only two days away, the entire football program seemed to shift gears. Towns and Crossland finished packing for the trip to New Haven. The coaches spent the morning polishing the game plan and reviewing the punting and kicking units. At noon, Tosches went off to the weekly luncheon that the university holds for the sporting press. Over cold cuts and soda, he told the handful of reporters who cover the Tigers that his team had “character” and needed to stop the Yale running game to win. He down played the Tigers’ twenty-two-year losing streak in the Yale Bowl. “We weren’t here twenty years ago,” Tosches said. “We’re concerned about the game on Saturday, not any kind of streak.”

In a closed-door meeting later that afternoon with the five quarterbacks on the varsity roster, Tosches turned teacher. “You might call this Football 404,” he said, rapidly drawing X’s and O’s on a chalkboard. Because of the trip to New Haven, this was the last full practice before Saturday’s game, and Tosches had a lot of material to cover. First he showed some more film of the Yale secondary. Then, speaking primarily to Jason Garrett, Tosches ran through a package of pass plays that had been worked into the offensive scheme especially for Yale. “These are all passes that we can protect, so stay in the pocket and get the ball off quickly,” he said. For some razzle-dazzle, Tosches included a fleaflicker and a reverse on the play list.

In the locker room, someone had put up posters that said, “Yale: Not Just Another Game” and “Kickoff, Kick Ass.” The team responded with its most spirited practice of the week. Although not as rigorous as Wednesday workouts (when the team finishes the day with six laps around the field), Thursday practices involve the most contact. At one end of the field, offensive linemen slammed into each other with abandon. Twenty yards away, running backs were throwing blocks at other running backs; at midfield, the defensive backs practiced open-field tackles. In exchange for not being hit, the kickers had to wait around in the cold, wind, and rain until the special teams took the field in the last ten minutes of practice.

Before heading to the dressing room, the team got a brief pep talk from Pete Milano ‘88, a linebacker on last year’s squad. When Milano started speaking, the coaches discreetly departed. “At a place like Princeton, you’re dealing with complicated, highly independent players,” Tosches said as we walked to the field house. “They’re all mature, determined, and goal-oriented, or else they couldn’t have gotten in here. As coaches, we have to appeal to their competitive side. We don’t have scholarships dangling over their heads.”

Compared to players in big-time college programs, Princeton gridders have remarkable freedom – no special dorms for athletes, no bed checks, no mandatory study halls, and, under the terms of an Ivy League rule, no drug or alcohol tests. They don’t receive the special academic treatment that athletes at other colleges sometimes receive, either. Like everyone else, football players struggle through junior papers and senior theses.

That evening after practice, I followed the herd to the elevator in the basement of New South and squeezed in with three offensive linemen. Once on the seventh floor, I saw some of the most ferocious eaters on the planet do battle with the best that the university’s Department of Food Services could offer. Tonight, the choice was between chicken and ravioli (most of the guys had both); these dishes were complemented with mounds of spaghetti, mashed potatoes, beans, rolls, salad, ice cream, apple pie, pumpkin pie, and blueberry cobbler. Other entrees during the week included prime rib, steak, and Seafood Newburg. The players are encouraged to go back for seconds.

At six feet and 240-plus pounds, Franco “Meals on Wheels” Pagnanelli is the undisputed champion trencherman on the 1988 squad. Pagnanelli generally stays in the main part of the cafeteria, close to the food. A group of his teammates, however, head for the television room in the back, where they devotedly watch the game show “Jeopardy.” On Thursday night, they were concentrating on a category called “First Names,” and three players blurted out “Cecil!” in response to a question about the financier Cecil Rhodes. The contestants in New South had less success with a category on “1979,” though, missing questions about a top song and the retirement from N.A.T.O. of General Alexander Haig. A lot of the players in the room were only ten years old then.

Friday, November 11

BY 9 A.M., when the first of the big tour buses that would take the team to New Haven pulled up to the field house, Caldwell was bustling with activity. The coaches wandered around, sipping Wawa coffee from paper cups and looking slightly uncomfortable in the suits and ties that are de rigueur on road trips. On a bench outside, manager K-T Graves sat with a list of all the players who were going to New Haven. As they arrived, she crossed their names off the list. Even though it was a chilly morning, K-T had to wait outside; Caldwell, built in 1966, was designed to serve an all-male student body. (Renovations are underway to expand the building and make it coed.)

As manager, K-T handles all the logistics, from setting out paper cups of water during practice to renting buses and making hotel reservations for away games. At some of the college football powerhouses, the undergraduate team manager holds one of the most lucrative and influential student posts. Not at Princeton. K-T doesn’t have any freshman or sophomore assistants to boss around, and she gets neither academic credit nor pay for her labors.

Coach Tosches strolled up at 9:30, and together we watched small clumps of players descend from the main campus. “Sometimes you see them sprinting across campus, pulling their shirts on as they go,” Tosches said. “It’s worst during midterm week – some of them have papers due on Friday, and they stay up all night before a road trip.” I asked him what happened if someone missed the bus. “They listen to the game on the radio,” he said. No extra pushups, no suspensions, no Knute Rockne tongue-lashings? “That doesn’t really work with these guys,” Tosches said. “Missing the game is punishment enough.”

Hank Towns and Cap Crossland were maneuvering one of the big equipment lockers into the belly of one of the buses. “We got to carry these mothers up three flights of stairs at Yale,” Towns groused, pointing to three other lockers and a pair of hampers full of linen. At least they didn’t have to contend with the hundred-odd bags of personal gear that were loaded in the other two buses. According to a policy established long ago, Crossland informed me, Princeton players tote their own gear, from street clothes to shoulderpads.

Everything and everybody was on board by ten, and the buses awkwardly peeled off in convoy formation for the three-hour drive to New Haven. When the last of the buses had gone, I found myself standing alone in the parking lot. No cheerleaders, no band, no alumni from the Friends of Football wishing the team well.

Saturday, November 12

WITH ITS massive earthen berms, Roman “portals,” and sunken playing field, the Yale Bowl recalls the kind of totalitarian architecture that one usually associates with Mussolini. Princeton has traditionally had problems in the bunkerlike Bowl; going into this year’s game, the Tigers had lost eleven in a row in New Haven, including a humiliating last-second defeat in 1986. Even so, the Tigers looked relaxed and confident

when they took the field shortly after noon for their warm ups. On the sideline, Towns and Crossland appeared, carrying a locker full of spare equipment, and Dick Malacrea set up his emergency taping ward at one end of the bench. Coach Tosches and Yale coach Carm Cozza stood chatting cordially near midfield.

The Elis won the toss and promptly marched the opening kickoff seventy-two yards in ten plays for a touchdown. Both Buddy Zachary, Yale’s star running back, and Darin Kehler, the quarterback, appeared to be unstoppable, and the fans in the Princeton stands prepared themselves for another dismal day in the Yale Bowl. But the Tigers’ offense looked equally unstoppable. Although Princeton’s first drive was halted by a holding penalty at the Yale 18, and although Lutz missed a thirty-five-yard field goal attempt, the backs and offensive linemen seemed unperturbed when they returned to the bench. The offensive game plan was working, and they knew it.

Sure enough, Princeton punched the ball into the end zone on its next possession. The highlight of the drive was a thirty-five-yard bomb from Jason Garrett to Mark Rockefeller on a broken play. Threatened by the Yale defensive line, Garrett scrambled around for an eternity before unloading the ball to Rockefeller, who made an acrobatic catch between two Yale defenders. A few plays later, Garrett found Dave Wix in the left corner of the end zone for the touchdown. Somers Steelman, pacing excitedly on the sideline, almost swallowed his cigar.

Neither team accomplished much else until thirty-nine seconds before halftime, when Frank Leal intercepted an errant Kehler pass and returned it to the Yale 44-yard line. Jason gunned a pair of quick passes to secure a first down, and then, with only seventeen seconds left, he calmly hit Wix for a 24-yard gain. Lutz trotted onto the field and booted Princeton to a 10-7 lead.

At the half, a couple of players told me later, Tosches forcefully reminded the Tigers that they were more than three points better than Yale. Apparently it took the Princeton players most of the third quarter to realize this, and they were lucky to survive a scoreless period. Mike Hirou ’91, the free safety, snuffed out one Eli drive with an interception deep in Princeton territory, and, late in the quarter, Bill DeFrancesco ’89 recovered a fumbled punt near midfield. This turnover seemed to spark the Tigers. Moments later, on the first play of the fourth quarter, Jason found Judd over by the right sideline – one of the “70” plays they had worked on in practice. Judd evaded the linebacker’s tackle and sped forty-nine yards for the touchdown, just as the coach had diagrammed it.

The Tigers exploited another interception by Leal to score the game’s final points, and only then – with about five minutes left to play and a 24-7 lead – did smiles begin to emerge on the Princeton bench. One of the broadest smiles belonged to Steelman, who stuffed his pockets with two-dollar Honduran cigars that he was going to pass out to the players in the locker room. “About time we won in New Haven,” he gloated. “Makes my life much easier.”

Long after the gun sounded to end the game, fans and players still mingled on the field. Jason Garrett and Mark Rockefeller signed autographs. The Princeton students in the crowd discussed plans for the traditional “Big Three” victory bonfire to mark Princeton wins over Harvard and Yale. Coach Depew, descending from the press box, groused that the game wasn’t “a defensive masterpiece” and went off to change. Malacrea appeared. “No serious injuries today,” he reported. “My idea of a good game.”

And Coach Tosches, remembering his last trip to the Bowl, savored the walk across the field to console Coach Cozza. “This year, I took it slow and enjoyed every step of the way,” he later said. Within twenty-four hours, he and his staff would be back in his darkened office, watching films and getting ready for Princeton’s next opponent on the schedule.