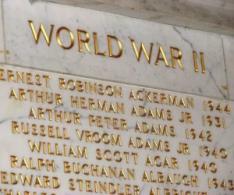

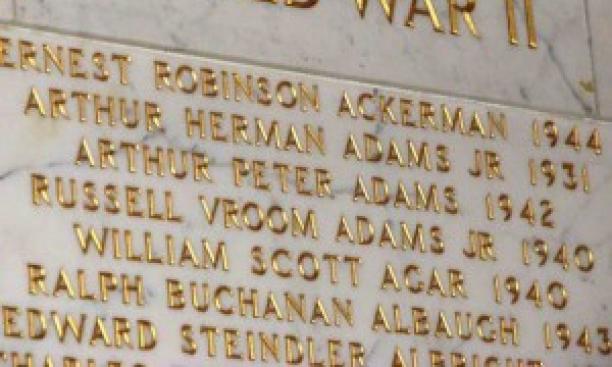

Just inside the wood paneled doors of Nassau Hall, the marble walls of the Memorial Atrium list the names of hundreds of Princeton alumni who have died serving in the line of duty since the founding of the University in 1746.

“Up on that wall they have veterans who have died from the Revolutionary War throughout all the conflicts [in American history],” explained a graduate student who, as an active member of the armed forces, asked not to be identified in this story. “What’s missing is Iraq and Afghanistan,” he said, referring to the two 21st-century wars that have claimed the lives of more than 6,000 Americans.

The absence of names from the most recent conflicts, while positive, also is symptomatic of growing disconnect between American society, along with its elite institutions, and the members of the armed forces, the graduate student argued.

It was the desire to bridge this divide that led him and his fellow veteran students at Princeton to form the Student Veterans Organization, which aims to serve as both a support group for veterans on campus and a facilitator of dialogue between those veterans and members of the Princeton community at large.

On Nov. 11, the Student Veterans Organization co-sponsored its first formal event, a Veterans Day panel at Robertson Hall featuring six Princeton-affiliated veterans reflecting on their service and discussing the very divide that led to the Student Veterans Organization’s formation last spring.

The panel, moderated by Paul Miles *99, a lecturer in Princeton’s history department, included alumni Bill Haynes ’50 and Charlie Rose ’50 as well as two active-duty soldiers and current graduate students who served in both Iraq and Afghanistan.

The panelists spoke about the problematic gap between American citizens and the soldiers who protect them, with many agreeing that the problem stems from a widespread lack of personal connection to members of the military and the inaccurate portrayal of veterans in the mainstream media. Speakers implored those in attendance to engage military veterans in sincere conversation, but many took issue with the phrase “thank you for your service,” arguing that while well intentioned, the line can be a conversation-stopping platitude.

While members of the Student Veterans Organization spoke positively of their time at Princeton, they said that the greatest obstacle to facilitating dialogue is the sheer lack of veterans and active military members on campus. Currently, the group is comprised of three professors, 12 graduate students, and the only undergraduate veteran, sophomore Michael Liao.

Liao said he has been warmly received by his class since arriving last fall after five years in the Marines. “Everyone I have talked to has always been interested in my service,” he said.

Yet he noted that of all Ivy League universities, Princeton is the only school with only one undergraduate veteran, a fact that he attributed both to the University’s policy of not accepting transfer students as well as its lack of outreach to members of the military.

For the Record

An earlier version of this post incorrectly identified the name of the Student Veterans Organization and the branch in which Michael Liao served.