What he’s reading: “The Great Swindle by Pierre Lemaitre, my favorite crime writer. It’s in the genre of Silence of the Lambs: supercop vs. psychopath. I love crime novels generally, and Lemaitre is at the top.”

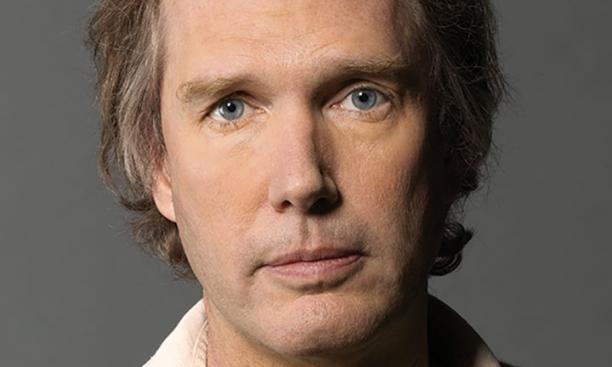

There’s a bedrock belief in the world of popular music: People’s tastes are established in their late teens and early 20s, and don’t change thereafter. There’s even some good social-science data to back this up. So John Seabrook ’81 is very much the exception when he reacts to his son’s interest in rhythmic pop — from Flo Rida’s “Right Round” to Katy Perry’s “Dark Horse” — by diving headlong into new sounds.

The spawn of that exploration is The Song Machine: Inside the Hit Factory, a portrait of the largely unknown producers who manufacture today’s digitally manipulated, multi-layered hit songs. Seabrook is a New Yorker writer who also plays guitar in the Sequoias, a Rolling Stones- and Neil Young-heavy cover band of writers that includes Seabrook’s boss, David Remnick ’81.

In the Internet age, when we’re empowered to wander into the infinite niches of the digital culture, hugely popular hit songs by Perry, Taylor Swift, and Britney Spears play an important role in building community, Seabrook says: “When I hear one of these songs on the radio of a passing car, it creates a feeling, a bond. It connects you to other people in a way that other art forms don’t.”

Seabrook goes to great lengths to reveal how a tiny band of producers builds hit tunes out of beats and hooks (the fleeting musical phrases that worm their way into the listener’s memory), rather than the melodies and lyrics that were the main ingredients of earlier eras’ hits. The songweavers — many of them Swedes — use digital tools to combine seductive chords from European dance music with American R&B grooves and a big choral sound from ’80s arena rock. They break the singer’s performances down to individual syllables — reconstructing each word in a song with bits from several different takes, each heavily computer-enhanced. The result, when it works, is songs that are deeply infectious.

The music business, as ever, is full of hustlers and con artists, and Seabrook profiles them with gusto, but he’s also keenly aware of how tech innovators have injected different values into the industry. The result is a tension that remains unresolved. Old-school musical passions bang up against new media realities, crumbling business models, and popular tastes that seem to shift at unprecedented speed.