Witherspoon’s books entered the collections of the Library in 1812. They were comingled with the 706 volumes of his son-in-law Samuel Stanhope Smith, purchased for the sum of $1,500. For decades Witherspoon’s books remained distributed within the working book stock of the Library, which totaled 7,000 volumes by 1816. After the Civil War, the surge of interest in leaders of the American Revolution included a focus on Witherspoon. At the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, the Presbyterians erected a statue of Witherspoon. Like his visage, his books were also of interest.

The hunt for the books began during the tenure of Frederick Vinton, librarian from 1873 until his death in 1890. There was no precise list of such. Evidence of ownership was based on two grounds: 1) Witherspoon’s signature and book number at the top of the title page (his usual practice) and 2) mention in the list of books in his son-in-law’s library. Only examination of the books themselves and comparison with the Smith list could affirm ownership.

Vinton recorded his findings on blank pages of an 1814 catalogue of the library. Varnum Lansing Collins, Class of 1893, served as reference librarian from 1895 to 1906. He regularized Vinton’s findings into an alphabetical list, perhaps in preparation for his biography of Witherspoon published in 1925. In the 1940s, during the tenure of librarian and Jefferson scholar Julian Boyd, curator Julie Hudson physically reassembled the Witherspoon books into a separate special collection with the location designator WIT. The project took years, resulting in a collection of more than 300 volumes. In addition to re-gathering the books, Ms Hudson oversaw repairs and rebinding by “Mrs. Weilder and Mr. [Frank] Chiarella of the PEM Bindery” [in New York.]

Since Ms. Hudson’s efforts, a few more Witherspoon books have come to light. During 1949-50, volume one of the third edition of Miscellanea Curiosa (London, 1726) was acquired by exchange. In 1963, Mrs. Frederic James Dennis gave Witherspoon’s copy of The Constitution of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America containing the Confession of Faith, the Catechisms, the Government and Discipline (Philadelphia, 1789), signed by him on the half title. In 1967, the Library purchased Witherspoon’s copy of Thomas Clap’s The Annals or History of Yale College (New Haven, 1766.) In 1978, the Library purchased Witherspoon’s copy of volume one of Jacques Saurin’s Discours historiques, critiques, theologiques, et moraux, sur les evenemens les plus memorables du Vieux, et du Nouveau Testament . (Amsterdam, 1720.) Lastly, there appeared in a 1998 auction in New Hampshire, Witherspoon’s copy of The Odes of Sir Charles Hanbury Williams, Knight of the Bath (London, 1768), however, this was not acquired and its current whereabouts are not known.

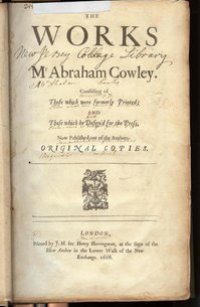

Perhaps if more of Witherspoon’s books are to be found today, then they are to be found in the collections here. This proved the case earlier this week. Now identified as Witherspoon’s is this entry in the Smith catalogue: “Works of Abraham Cowley …. 1 Folio.”

Boss Carnahan [President of Princeton, 1823-1859]Johnny Maclean [Vice-president under Carnahan]Boss Rice [Rev. B. H. Rice, D.D., served in Princeton pulpit, 1833 to 1847], Cooley [Rev. E.F. Cooley], Daniel McCalla, Petin the boot black, Moses Hunter, Albert Ribbenbach [?], Old Quackenboth (Uncle Joe), Buddy Be Dash, Catling Ross [?], Goose Leg.