Among the earliest silent films that were shot on the Princeton campus are those produced and financed by the classes of 1921 to 1939 (see our previous blog). The first true ‘class film’ was titled “The Class of 1923–its deeds and its antics.” A compilation of footage from this film and of the film “Champions 1922,” with football highlights of the fall of 1922, survive in the archives. Be ready to watch the “football team that wouldn’t be beaten,” the building of a championship bonfire, a dirty flour fight, Triangle chorines and more Princeton lore.

The two 16mm film reels on which this footage was found contain almost all scenes (though in different order) of the original nitrate base films that were kept by the Graduate Council. According to the Graduate Council’s lists of captions or “titles” of the films, the original “Champions 1922,” which was rented out to alumni groups, took up one reel, and the film with the class’ “deeds and antics” took up six. Portions of six of the seven original reels were used, with only the class’ commencement scenes omitted.

Princeton’s three football victories that clinched the championship in the fall of 1922 are found at separate places: the Yale game (November 18) at 0:00, the Harvard game (November 11) at 3:18, and the Chicago match (October 28, 1922) at 11.42.  The film features a live tiger cub (2:33) that, according to the note found with the film reel, was donated by the father of one of the players “since Princeton won (the) Harvard game.” An article in the Prince identifies the donor as J.F. Howard from Haverhill, MA, father of Albert “Red” F. Howard ’25, who had caught the cub while hunting in the jungles of India. The note indicates that the tiger was given to Philadelphia Zoo after graduation.

The film features a live tiger cub (2:33) that, according to the note found with the film reel, was donated by the father of one of the players “since Princeton won (the) Harvard game.” An article in the Prince identifies the donor as J.F. Howard from Haverhill, MA, father of Albert “Red” F. Howard ’25, who had caught the cub while hunting in the jungles of India. The note indicates that the tiger was given to Philadelphia Zoo after graduation.

To our surprise, we had already seen the bonfire footage at 4:22. It was featured in Gerardo Puglia’s 250th anniversary documentary and was thought to be the championship bonfire of 1926 when it was put online by the Princeton Alumni Weekly. Now we know that it was actually the championship bonfire of November 21, 1922. Given the caption on 1923’s Class film, it is easy to understand the mistake: it was traditionally the task of the freshmen (in this case the Class of 1926) to find wood for the celebratory bonfires. That this involved quite a bit more than gathering brushwood is demonstrated in the film. A photo montage of the events can be found in the Daily Princetonian of November 25, 1922.

Another Princeton tradition depicted on the film is the annual “flour picture,” the first photograph of the freshmen class on the steps of Whig or Clio Hall, which was taken after the sophomores dumped flour on the freshmen. The seniors of 1923 were merely bystanders when the Class of 1926’s flour picture was filmed on October 30, 1922 (5:40). The footage must have ended up here because the Class of 1923 had taken the initiative for the combined Motion Picture Committee that would coordinate the class films for all four classes, including the filming of the freshmen’s flour picture. (See our previous blog.)

The title that accompanied the original footage apparently was removed: “Flour (?) picture: 1926 undergoes its baptismal rites.” The question mark indicates that more than flour was dumped during this hazing ritual, and a year later, the Class of 1926, now sophomores, added their own special ingredient to the mix: acid! Not surprisingly, the flour picture was abolished immediately. The Prince wrote solemnly: “This action was necessitated by the degeneration of the Flour Picture in recent years until this fall it was a distinctly non-Princeton affair.” A later article detailed what may have been mixed with the flour on this footage: eggs, tar, paint, molasses “and whatnot.” The flour picture was reinstated in 1924 with water and flour only, but the interest of the sophomores waned, and the practice stopped after 1925.

The title that accompanied the original footage apparently was removed: “Flour (?) picture: 1926 undergoes its baptismal rites.” The question mark indicates that more than flour was dumped during this hazing ritual, and a year later, the Class of 1926, now sophomores, added their own special ingredient to the mix: acid! Not surprisingly, the flour picture was abolished immediately. The Prince wrote solemnly: “This action was necessitated by the degeneration of the Flour Picture in recent years until this fall it was a distinctly non-Princeton affair.” A later article detailed what may have been mixed with the flour on this footage: eggs, tar, paint, molasses “and whatnot.” The flour picture was reinstated in 1924 with water and flour only, but the interest of the sophomores waned, and the practice stopped after 1925.

The photographer of the flour picture is probably Orren Jack Turner, who appears at 6:28, followed a bit later by B.F. Bunn ’07 (6:36), manager of the University store and financial adviser to many campus organizations, who advanced the money for the camera purchased by the Motion Picture Committee. The footage of Bunn is followed by scenes from the Triangle show “The Man from Earth” (6:46), the annual show for 1922-1923, with Wally Smith ’24 in the title row, singing “That’s why I left the world behind” (7:36). This is the earliest Triangle footage in the University archives, preceding even the footage of “The Golden Dog” of 1929 that was featured in a previous blog.

The remainder of the footage includes athletic teams and training sessions, as well as class officers and members of the boards. Sports featured include soccer (1:21, 5:28), cross country (2:15), baseball (7:49. 14:31), rowing (8:25. 17:33) and golf (16:12), while footage of construction of the Hobart Baker ice hockey rink can be found at 6:42. The footage includes members of Theatre Intime (14:00) and the board of the Daily Princetonian. The latter footage captures another Princeton’s tradition: the privilege, exclusive to seniors, to sit on the steps of the Mather Sundial, in the center of McCosh Courtyard (16:44).

The remainder of the footage includes athletic teams and training sessions, as well as class officers and members of the boards. Sports featured include soccer (1:21, 5:28), cross country (2:15), baseball (7:49. 14:31), rowing (8:25. 17:33) and golf (16:12), while footage of construction of the Hobart Baker ice hockey rink can be found at 6:42. The footage includes members of Theatre Intime (14:00) and the board of the Daily Princetonian. The latter footage captures another Princeton’s tradition: the privilege, exclusive to seniors, to sit on the steps of the Mather Sundial, in the center of McCosh Courtyard (16:44).

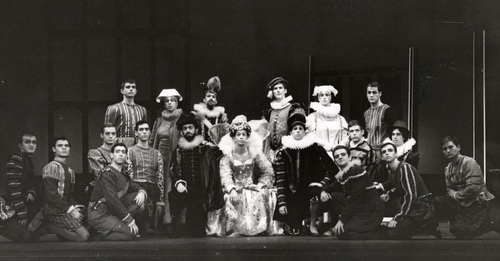

Filming of the comedy “Arthur Penrose” (1923) (Photo The Princeton Bric-a-Brac,1925)

Filming of the comedy “Arthur Penrose” (1923) (Photo The Princeton Bric-a-Brac,1925)