By Catherine Zandonella, Office of the Dean for Research

People are often said to have “learning styles” – for example, some people pay attention to visual details while others grab onto abstract concepts and meanings. A new study from Princeton University researchers found that changes in pupil size can reveal whether people are learning using their dominant learning style, or whether they are learning in modes outside of that style.

The researchers found that pupil dilation was smaller when people learned using their usual style and larger when people diverged from their normal style. The study was published in the journal Nature Neuroscience.

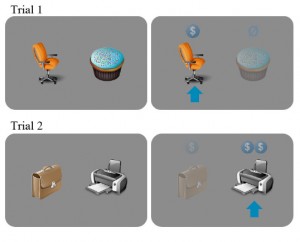

The study compared brain activity in individuals with two different learning styles – those who learn best by absorbing concrete visual details and those who are better at learning abstract concepts or meanings.

“We showed that changes in pupil dilation are associated with the degree to which learners use the style for which they have a predisposition,” said Eldar Eran, a graduate student in the Princeton Neuroscience Institute, who led the study.

The researchers used changes in pupil size as an indicator of variations in “neural gain,” which can be thought of as an amplifier of neural communication: when gain is increased, excited neurons become even more active and inhibited neurons become even less active. Smaller pupil dilation indicates more neural gain and larger pupil dilation indicates less neural gain.

The team showed that neural gain was correlated with different modes of communication between parts of the brain. In studies of human volunteers undergoing brain scans, when neural gain was high, communication tended to be tightly concentrated in certain regions of the brain that govern specific tasks, whereas low neural gain is associated with communication across wider regions of the brain.

“We showed that the brain has different modes of communication,” said Yael Niv, assistant professor of psychology and the Princeton Neuroscience Institute, “one mode where everything talks to everything else, and another mode where communication is more segregated into areas that don’t talk to each other.” The study also involved Jonathan Cohen, Princeton’s Robert Bendheim and Lynn Bendheim Thoman Professor in Neuroscience.

These modes are linked to the level of neural gain and to learning style, Niv said. Neural gain can be thought of as a contrast amplifier that increases intensity of both activation and inhibition of communication among brain areas. “If one area is trying to activate another, or trying to inhibit another – both effects are stronger, everything is more potent,” she said. “This is correlated with communication being segregated into clusters of activation in the brain, so each network is talking to itself loudly, but connections across networks are inhibited. In situations of lower gain, however, the areas can talk to each other across networks, so information flows more globally.”

“These two modes [of communication in the brain] seem to be associated with different constraints on learning,” she said. “According to our study, in the mode where everything talks to everything, learning is very flexible. In contrast, in the mode where communication is stronger and more focused, but also more segregated between brain areas, subjects were more true to their personal learning style. Neither of these modes are better than the other – in both cases participants were equally successful in the task, but in different ways.”

“We interpreted these results to mean that although we tend to have a dominant learning style, we are not a slave to that style, and when operating in the proper mode, we can overcome dominant styles to learn in other ways,” she said.

This research was funded by NIH grants R03 DA029073 and R01 MH098861, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute International Student Research fellowship, and a Sloan Research Fellowship. The authors also wish to thank the generous support of the Regina and John Scully Center for the Neuroscience of Mind and Behavior within the Princeton Neuroscience Institute.

Eldar, Eran, Jonathan D Cohen & Yael Niv. 2013. The effects of neural gain on attention and learning. Nature Neuroscience. Published online June 16, 2013 doi:10.1038/nn.3428

You must be logged in to post a comment.