by John Greenwald, Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory

Completion of a promising experimental facility at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Princeton Plasma Laboratory (PPPL) could advance the development of fusion as a clean and abundant source of energy for generating electricity, according to a PPPL paper published this month in the journal IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science.

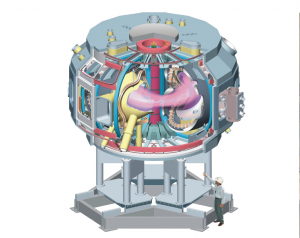

The facility, called the Quasi-Axisymmetric Stellarator Research (QUASAR) experiment, represents the first of a new class of fusion reactors based on the innovative theory of quasi-axisymmetry, which makes it possible to design a magnetic bottle that combines the advantages of the stellarator with the more widely used tokamak design. Experiments in QUASAR would test this theory. Construction of QUASAR — originally known as the National Compact Stellarator Experiment — was begun in 2004 and halted in 2008 when costs exceeded projections after some 80 percent of the machine’s major components had been built or procured.

“This type of facility must have a place on the roadmap to fusion,” said physicist George “Hutch” Neilson, the head of the Advanced Projects Department at PPPL.

Both stellarators and tokamaks use magnetic fields to control the hot, charged plasma gas that fuels fusion reactions. While tokamaks put electric current into the plasma to complete the magnetic confinement and hold the gas together, stellarators don’t require such a current to keep the plasma bottled up. Stellarators rely instead on twisting — or 3D —magnetic fields to contain the plasma in a controlled “steady state.”

Stellarator plasmas thus run little risk of disrupting — or falling apart — as can happen in tokamaks if the internal current abruptly shuts off. Developing systems to suppress or mitigate such disruptions is a challenge that builders of tokamaks like ITER, the international fusion experiment under construction in France, must face.

Stellarators had been the main line of fusion development in the 1950s and early 1960s before taking a back seat to tokamaks, whose symmetrical, doughnut-shaped magnetic field geometry produced good plasma confinement and proved easier to create. But breakthroughs in computing and physics understanding have revitalized interest in the twisty, cruller-shaped stellarator design and made it the subject of major experiments in Japan and Germany.

PPPL developed the QUASAR facility with both stellarators and tokamaks in mind. Tokamaks produce magnetic fields and a plasma shape that are the same all the way around the axis of the machine — a feature known as “axisymmetry.” QUASAR is symmetrical too, but in a different way. While QUASAR was designed to produce a twisting and curving magnetic field, the strength of that field varies gently as in a tokamak — hence the name “quasi-symmetry” (QS) for the design. This property of the field strength was to produce plasma confinement properties identical to those of tokamaks.

“If the predicted near-equivalence in the confinement physics can be validated experimentally,” Neilson said, “then the development of the QS line may be able to continue as essentially a ‘3D tokamak.’”

Such development would test whether a QUASAR-like design could be a candidate for a demonstration — or DEMO —fusion facility that would pave the way for construction of a commercial fusion reactor that would generate electricity for the power grid.

George Neilson, David Gates, Philip Heitzenroeder, Joshua Breslau, Stewart Prager, Timothy Stevenson, Peter Titus, Michael Williams, and Michael Zarnstorff. Next Steps in Quasi-Axisymmetric Stellarator Research IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science, vol. 42, No. 3, March 2014.

The research was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy under contract DE-AC02 09CH11466. Princeton University manages PPPL, which is part of the national laboratory system funded by the U.S. Department of Energy through the Office of Science.

You must be logged in to post a comment.