The Racialization of Size: A National Project

Image-searching the phrase “beautiful Argentine women” on Google yields disappointingly homogeneous results: none of the eighteen images that appear on the first page features a dark-skinned or voluptuous woman. Indeed, images of thin, white, bikini-clad women dominate the first several pages of results, providing a crucial glimpse into the aesthetic ideals of the South American country. Best known for its steak and wine—both consumption and production—Argentina is now (perhaps ironically) making an international name for itself with its skyrocketing rates of eating disorders. While changing eating and exercise patterns associated with Westernization are surely involved in the recent explosion of anorexia nervosa and bulimia, there are clearly national and racial elements at play as well. In discussing the history of mestiçagem in neighboring Brazil and its role in the national discourse surrounding beauty and race, Alexander Edmonds notes the emergence of “female beauty as a kind of national patrimony” (2007: 88). He argues that the widespread historic miscegenation within Brazil has lead to a concept of “meta-racialization” in which race is first ignored and then reinscribed on the mestiza’s nationalized body. The result, he claims, is that “the aesthetics of the female body are viewed in a national register” (2007: 89).

This nationalization of the female body is prevalent in Argentina as well. In her piece “The Critical Aesthetics of Disorder: A Porteña Crisis of Size”, Melissa Maldonado-Salcedo claims that “porteñas embody the national crisis of identity” such that “porteñas continue to be seen as Argentina’s best representation of ‘European modernity’” (2010: 40-41). The result made clear in newspaper articles, cartoons, blogs, and other sources, is the association of civilization with whiteness, thinness, and urbanity, while “barbarism is visually juxtaposed as rural, dark, and fat” (2010: 39). The consequences of such associations are severe: indeed, rising rates in eating disorders in Argentina (and the rest of Latin America) are undoubtedly connected to perceptions of European white thinness as beautiful, thus prompting women who do not fit this mold to feel ugly, worthless, and un-Argentinian. Eating disorders are then characterized as issues of white, upper-class, “civilized” women, while women of other racial groups are perceived of as “immune” to the appeal and pull of such notions of beauty. This racialization of size is, paradoxically, perhaps most clear in the invisibility of curvaceous black women in Argentina: determined to be modern, civilized, and European, the curvaceous black woman is the antithesis of such goals and is thus hidden, either by herself or by an Argentinian media which does not want to recognize the “ugly” segments of its population.

The association between thinness and whiteness is clear in the newspaper article “Prisoners of Perfection” from the San Francisco Chronicle 1. A model is quoted: “women here are too preoccupied with how they look, how thin they are. They all get operations, dye their hair blond—it is excessive” 2. Not only are women manipulating their body shape to adhere to cultural ideals, they are also tinkering with other characteristics, notably hair color, to embody the epitome of whiteness. Interestingly, someone benefitting from her culture’s fondness for thinness is also criticizing it, perhaps illustrating the extent to which such discourses have been internalized and normalized. The article continues on to highlight the cases of two Argentinian girls who suffered from anorexia and bulimia: they are identified as “a cheerful 17-year-old brunette” and “a 22-year-old blond university psychology student” 3. Given Argentina’s insistence on its European heritage and its near denial of any indigenous origins, the racial markers used in these instances are notable: both women featured in the article are white. In a similar article from the Chicago Tribune titled “Anorexia Wasting Pre-Teens in Argentina”, the highlighted individual is a “4-year-old with curly blond hair…[who] had begun watching television diet shows, refusing to eat bread and vomiting after eating sweets” 4. At one point the article notes, “in Buenos Aires…thin is always in,” but perhaps a more complete statement would be: “in Buenos Aires…being white and thin is always in” 5.

Argentina’s desire to be perceived as a modern European nation (rather than an uncivilized Latino nation) is central to discourses surrounding body, beauty, and race. In their piece “Argentina: The Social Body at Risk,” Oscar Meehan and Melanie Katzman note that “modern-day Argentinians define their differences from their neighbors by preference to…dialect, skin colour, and education” (2001: 142). They explain that this may “prompt [Argentinian’s] over-identification with Europe as a way of confirming differences, affirming one’s ‘civility’ and acculturating to an established society” (2001: 143). Frances Negrón-Mutaner expands on this notion in her piece “Jennifer’s Butt”, noting that “a big culo [butt] does not only upset hegemonic (white) notions of beauty and good taste, it is a sign for the dark, incomprehensible excess of “Latino” (2003: 295). Taken together, it becomes clear that “latinidad”—and its associated “curvaceousness”—is, in essence, “un-Argentinian”. Thus the “national register” of Argentina can be considered a racializing gaze upon the shapes of women’s bodies.

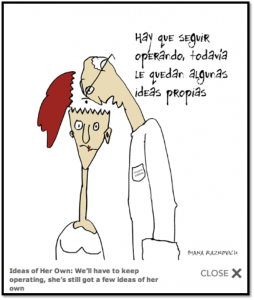

Perhaps the best representations of this “racialization of size” are the cartoons by Argentinian cartoonist Diana Raznovich 6. The daughter of Jewish Russian immigrants, Raznovich’s work focuses on women’s issues, most notably ideas about subordination, confinement, and submission. Each of Raznovich’s cartoons satirizes, challenges, and questions dominant notions of beauty and their relationship to women’s (racialized) bodies. “Ideas of Her Own” depicts a white male doctor (as identified by his white jacket) peering into the sawed open head of a white female. The caption reads: “we’ll have to keep operating, she’s still got a few ideas of her own”. By using a white female as the subject of this cartoon, Raznovich is implicitly reaffirming notions of the white female as particularly vulnerable to the influence and authority of a male-dominated Argentinian society.

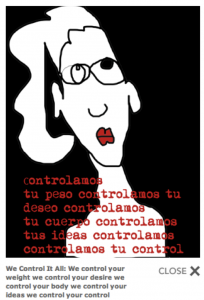

“Thin 5” features a white female whose body has been doubly violated: first, by the black lines drawn across it, and again by the words deliberately written across it. The words inserted in the image 7 again critique dominant practices of body and beauty; indeed, phrases such as “subjected to”, “all alike”, and the repetition of “anti” emphasize the passivity and subordination of (particularly white) women with regard to the very notions against which they are judged. In “We Control It All,” Raznovich again utilizes a white woman, this time with exaggerated lips. The woman is (conspicuously) pictured only from the shoulders up (that is, she is body-less) and the text reads: “we control your weight we control your desire we control your body we control your ideas we control your control”. The lack of punctuation seems deliberate and gives the text an almost robotic quality, suggesting that (white) women’s participation in practices of body and beauty are mindless, merely the mechanized and automatic motions of brainwashed drones.

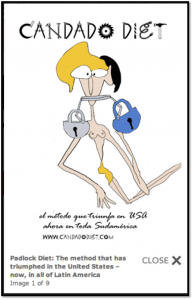

“Padlock Diet” depicts a blond, exaggeratedly thin white female figure whose mouth is sealed by two exaggeratedly large padlocks. The caption reads: “the method that has triumphed in the United States—now, in all of Latin America”. Here, the caption suggests that the eating disorders of Argentina and the rest of Latin America are “imported” from the United States, a notably “white” country, and are imprisoning an otherwise innocent and naïve population.

“Gordas” is perhaps Raznovich’s most famous cartoon. It depicts a relatively large white man standing in front of a line of dramatically thin female bodies. The women are all standing in the same posture in a straight line and are all standing naked aside from underwear, shoes, and some hair accessories. While three of the fifteen women depicted are racially marked (i.e. either morena or black), the majority is still certainly white. The man is wearing some sort of uniform and seems to be yelling “GORDAS!!” (“fat women!!”) at the women standing in front of him.

This cartoon is a powerful statement regarding notions of body, beauty, and race in Latin America (and specifically Argentina). The women are almost like soldiers, thoughtlessly carrying out the orders of their leader (the man). His emphatic scream toward the women reiterates the order-like nature of his comments. The women seem like mere copies of one another, unable to foster individuality or create unique identities, and wholly passive to the orders and commands of the man who stands before them.

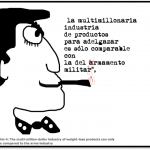

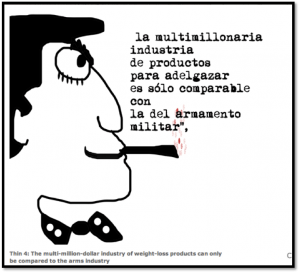

The role of this passivity in the nation building of Argentina is made evident in Raznovich’s cartoon “Thin 4”. Though this cartoon does not feature a white female, it depicts a white male smoking a cigarette with the caption: “the multi-million dollar industry of weight-loss products can only be compared to the arms industry”. The man—possibly a politician, based on his necktie, or another influential figure—can thus be interpreted to represent authority, dominance, and power. Just as the arms industry is vital in nation building and in the formation of a national identity, so too is the manipulation of women’s bodies. By using an “authoritative” man in this cartoon, Raznovich is asserting that the significance given to shape, size, race, and women’s bodies likely has a political agenda.

Together, these sources all point to a trend in which size and shape are increasingly racialized and imbued with hierarchical value. While civilization and modernity are associated with whiteness and thinness, and thus by extension also elegance, sensuality, youth, and beauty, barbarism is connected to racial darkness, fat, dirtiness, and laziness. The result of such associations is the explosion of eating disorders in Latin America, especially Argentina, as women sense their inability to conform to these unrealistic ideals. While other factors are certainly at play in the development of eating disorders, it seems significant that these disorders are correspondingly racialized with the group most expected to embody them. Such expectations leave little room for the experiences of colored women (and men). Unheard and unrecognized, these individuals’ experiences are ignored and unaddressed, thus further reinforcing notions of eating disorders as white phenomena.

Because of its strong cultural (and indeed ancestral) connections to Europe, Argentina serves as the perfect breeding ground for the rise of racialized conceptions of female size and shape. A dominantly white population, Argentinians are subjected to unrealistic and unattainable ideals linking thinness and whiteness with modernity. Determined to prove its similarity to European countries, Argentina has created a culture in which deviation from such cosmetic ideals is to nearly renounce citizenship to Argentina. Thus, the racialization of size and body can be interpreted as a national project to prove and maintain the modernity of Argentina. By spurning those who digress from these ideas and norms, Argentinian culture aims to disaffiliate them from the nation and thus create a nation of flawless white beauty. Unlike its neighbor, Brazil, Argentina has no desire to embrace the mixture that created its present population: it would rather pretend that such mixture never took place at all.

Bibliography

Edmonds, Alexander (2007) ‘Triumphant Miscegenation: Reflections on Beauty and Race in Brazil’, Journal of Intercultural Studies, 28, 1: 83-97.

Glickman, Nora (2009) “Diana Raznovich”, Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia. Jewish Women’s Archive. <http://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/raznovich-diana>. Accessed May 14th 2012.

Goering, Laurie (1997) ‘Anorexia Wasting Pre-Teens in Argentina’, The Chicago Tribune. 15.12.1997.

Love, Elizabeth (2000) ‘Prisoners of Perfection’, The San Francisco Chronicle. 19.10.00.

Maldonado-Salcedo, Melissa (2010) ‘The Critical Aesthetics of Disorder: A Porteña Crisis of Size’, Formations, 1, 1: 39-64.

Meehan, Oscar L. and Katzman, Melanie A. (2001) ‘Argentina: The Social Body at Risk’, in Nasser, Mervat, Melanie A. Katzman and Richard A. Gordon (eds.) Eating Disorders and Culture in Transition. New York: Brunner-Routledge; 138-161.

Negrón-Montaner, Frances (2003) ‘Jennifer’s Butt’ in M. Gutmann, Matos Rodríguez, F. V., Stephen, L., et al. (eds) Perspectives on Las Américas: A Reader in Culture, History and Representation. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers; 291-298.

All cartoons are by Diana Raznovich and were found here: http://hemi.nyu.edu/journal/4.2/eng/en42_pg_raz.html

- http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2000/10/19/MN1646.DTL&ao=all ↩

- As footnote 1 ↩

- See footnote 1 ↩

- http://articles.chicagotribune.com/1997-12-15/news/9712150040_1_buenos-aires-anorexia-bulimia ↩

- As footnote 4 ↩

- Diana Raznovich is an Argentinian playwright, poet, and cartoonist. Born in Buenos Aires, Raznovich’s parents were Jewish-Russian immigrants to Argentina. Much of her work seeks to condemn mainstream culture by highlighting its contradictions, inconsistencies, and falsities. Her criticisms are often directed at women’s issues (such as confinement and subordination to men) and are influenced by her Jewish upbringing ↩

- Thin 5. The global industry of women.

Woman-objects designed

To consume products

Anti-aging

Anti-cellulite

anti-liposity

anti-personality

women, all alike

well-formed bones

skin and bones

women with adolescent bodies forever, armies of

women subjected

to dietary regimes, to

liposuction,

silicone treatments,

face lifts ↩