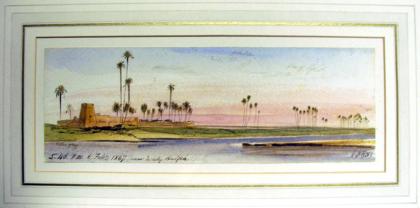

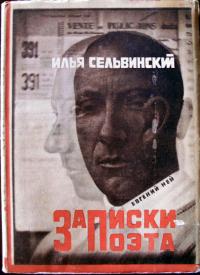

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851), First sketch of group of fish in The Slave [Ship], Robert Taylor Collection RTC01

The great English painter Joseph Mallord William Turner loved the sea. Beginning in 1829, he spent periods of time each year at the seaside house of Mrs. Sophia Booth in Margate. Later, the twice-widowed Mrs. Booth moved in with Turner in his Chelsea residence, where he enjoyed being greeted as Admiral Booth.

In 1840, at the age of 64, Turner painted Slave Ship, which received nothing but condemnation from the critics. Not only did they hate the loose brushwork and violent palette but found the scene’s shocking depiction of slaves being thrown to their death unacceptable for a public gallery. Next to the painting, Turner hung a poem he called Fallacies of Hope:

Aloft all hands, strike the top-masts and belay;

Yon angry setting sun and fierce-edged clouds

Declare the Typhoon’s coming.

Before it sweeps your decks, throw overboard

The dead and dying - ne’er heed their chains

Hope, Hope, fallacious Hope!

Where is thy market now?

Slave Ship, 1840. Oil on canvas. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

One of the only voices to speak up for Turner was that of art critic John Ruskin (1819-1900), who was moved to begin writing an article about Turner and contemporary painting. This led to a lifetime work in five volumes, beginning in 1843 with the infamous volume one of Modern Painters (Ex 3915.1.3645).

Turner died eight years later at his Chelsea home with Mrs. Booth and was buried in St Paul’s Cathedral. His paintings were bequeathed to England and his fortune to a charity for male artists. Although Ruskin did not accept the offer to be an executor of Turner’s will, he did sort through the drawings in the Turner Bequest and curate an exhibition of them at Marlborough House in 1856-57.

A number of works remained with Mrs. Booth and it was from her that Ruskin purchased this watercolor study in 1880. In it, Turner worked out the fish for the lower right corner of The Slave Ship. Years later, it was purchased by Robert Hill Taylor (1908-1985), Class of 1930, and ultimately, donated to Princeton University.

BTW, the Princeton University Art Museum is the fortunate owner of a Turner sketchbook, which Ruskin purchased in 1860 and Charles J. Mosmann, Jr., Class of 1950, donated in 1957.

Recent Comments