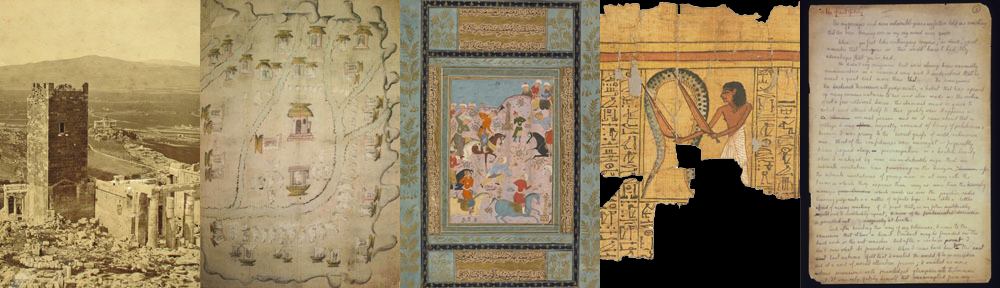

This fall, the Princeton University Art Museum is exhibiting the Peck Shahnamah, the Manuscripts Division’s finest Persian illuminated manuscript, in the exhibition Princeton’s Great Persian Book of Kings, on view from 3 October 2015 to 24 January 2016. Accompanying the exhibition is a catalogue chiefly prepared by Shreve Simpson, the guest curator, with contributions by Louise Marlow. The catalogue includes full-color reproduction of all illustrations (using new photography by Roel Muñoz, the Library’s Digital Imaging Manager, and Beth Wodnick Haas, Digital Imaging Technician).

In 1983, Clara S. Peck bequeathed her sumptuous manuscript of Firdawsi’s Shahnamah of 1589/90 (Islamic Manuscripts, Third Series, no. 310), to the Princeton University Library, in honor of her brother Fremont C. Peck, Class of 1920. Unfortunately, the manuscript had various binding and condition problems that made it difficult to use or exhibit. The Peck Shahnamah is a treasure of Safavid book illumination and was never dismembered like the Houghton Shahnamah and many other extraordinary Persian manuscripts. In consultation with the Library’s Preservation Office and several historians of Islamic art, Don C. Skemer, Curator of Manuscripts, proposed undertaking the much-needed conservation treatment and using it as an opportunity to display the Peck Shahnamah’s miniatures and other illuminated leaves at the Art Museum. This exhibition would not have been possible without the accomplished professional staff of the Library’s Preservation Office.

Conservation of the Peck Shahnamah began in 2014, when Mick LeTourneaux, the Library’s Rare Book Conservator, disbound the manuscript. It was in an elegant gold-tooled, red morocco English binding of around 1780, which was tight, stiff, and highly dysfunctional, not to mention inappropriate for an Islamic manuscript. It took Mick LeTourneaux almost two weeks to document and disbind this substantial 475-folio manuscript, separate the illustrated and text leaves, and put them in separate enclosures, awaiting conservation treatment and new digitization in the Library’s Digital Studio. In the process, he discovered that the binder had used large amounts of hide glue, which leeched into the manuscript itself. In addition, the English binder had often crudely cobbled the manuscript leaves into quires and then aggressively trimmed the edges, with resulting losses to the border decoration. Subsequent paper repair, probably during the 19th century, was also noted.

In 2015, after the manuscript had been disbound, Ted Stanley, Special Collections Paper Conservator, began the arduous process of examining the paper supports and pigments in order to determine an appropriate course of conservation treatments for both the illustrated and text leaves. In Persian illuminated manuscripts of the Safavid period, pigments are often the cause of conservation problems. The most problematic pigment is verdigris (basic copper acetate), a pale-green colorant that has been used since antiquity. Verdigris is made by exposing copperplates to acetic acid, usually in the form of vapors from vinegar. The pigment is highly acidic and corrosive when applied to paper and other cellulose-based materials.

In the Peck Shahnamah, rectangular verdigris frames surrounding the illuminations and text areas have been slowly eating their way through the paper since the sixteenth century. As a result, all of the frames were either weakened or broken. In addition, verdigris pigments used in the paintings themselves also weakened the paper support. The verdigris frames had to be reinforced with heat-set tissue, and the versos of illuminations were reinforced as well as appropriate. Verdigris used as a pigment in the miniatures resulted in staining to the versos of the pages. An alkaline-based conservation agent was applied to the versos to counteract the deteriorating effects of the verdigris. Unfortunately, there were many clumsy repairs done to the manuscript long before it was bequeathed to the Princeton University Library, and some had to be left in place because of the fragility of paper supports and the solubility of the pigments that they covered.

Ted Stanley discovered an overall loss of pigment in certain areas due to the mechanical action of turning manuscript pages because of the English binding. A microscopic examination of the pigments found they suffered varying degrees of loss. Most affected was the orange colorant, which spectroscopic examination determined to be red lead (lead tetroxide). There were much smaller amounts of loss with the other pigments, such as vermilion, a bright red made from cinnabar (mercury sulfide), and deep blue (lapis lazuli). The pigments that remain appear to be stable and did not require pigment consolidation. But among the pigments found spectroscopically was orpiment (arsenic sulfide), a yellow colorant that was very stable, but stained other colors that were in contact with it. There was very minute loss of lead white (basic lead (II) carbonate) overall. Lead white also was mixed with other colors to produce lighter shades.

Ted Stanley worked on conservation of the Peck Shahnamah’s illustrated and text leaves over the course of many months, and was also responsible for matting and framing 58 illustrated leaves and bifolia for the exhibition at the Princeton University Art Museum. Once the exhibition ends in January 2016, he will remove the leaves from the frames and mats so that the conservation effort can be completed. At this point, Mick LeTourneaux will begin the work of reassembling the manuscript in quires and sewing it in an appropriate Islamic-style binding. This work is expected to take several months. In the end, another treasure of Islamic civilization has been saved by the Library as part of its institutional commitment to responsible custody of extraordinary manuscript collections.

In 2012, the Library put the entire Peck Shahnamah online (including both illuminated and text pages) in the Princeton University Digital Library (PUDL), about which there is a separate blog post.

Ted Stanley preparing conservation

treatment reports for the manuscript.

You must be logged in to post a comment.