-

This Week in Princeton History for March 13-19

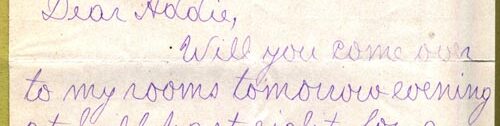

In this week’s installment of our recurring series, juniors make plans, an activist housewife is on campus, and more. March 15, 1869—Samuel Rene Gummere (Class of 1870) writes to classmate Adrian Hoffman Joline to invite him to a game of Whist in Gummere’s dorm room tomorrow night. March 16, 1971—Halfway through her 450-mile walk from…

-

This Week in Princeton History for August 22-28

In this week’s installment of our recurring series, royals take a tour, an athletic meet for Chinese students is held on campus, and more. August 25, 1975—Royalty from Monaco—Princess Grace, Prince Rainier, and their children, Caroline and Albert—visit Princeton on a tour of American colleges that includes Williams and Amherst. August 26, 1819—A letter to…

-

This Week in Princeton History for November 15-21

In this week’s installment of our recurring series, Blair Hall gets a new electric clock, Noah Webster gives a Princetonian credit for an idea, and more. November 16, 1899—The Alumni Princetonian notes that a clock has been installed on the Blair Hall tower and will be powered by electricity. November 18, 1821—Noah Webster writes that…

-

This Week in Princeton History for September 28-October 4

In this week’s installment of our recurring series bringing you the history of Princeton University and its faculty, students, and alumni, a crisis delays dorm heating, a yellow fever epidemic has interrupted campus operations, and more. September 28, 1819—A visitor to Princeton’s Junior Orations observes that during one of the student speeches, the audience was…

-

George Morgan White Eyes, Racial Theory at Princeton, and Student Financial Aid in the Eighteenth Century

In 1779, a group of Delaware set up camp on Prospect Farm, owned by George Morgan, along a dirt walkway that separated them from the campus of the College of New Jersey, as Princeton University was named until 1896. They brought a boy with them who was about eight or nine years old. His father…

This blog includes text and images drawn from historical sources that may contain material that is offensive or harmful. We strive to accurately represent the past while being sensitive to the needs and concerns of our audience. If you have any feedback to share on this topic, please either comment on a relevant post, or use our Ask Us form to contact us.