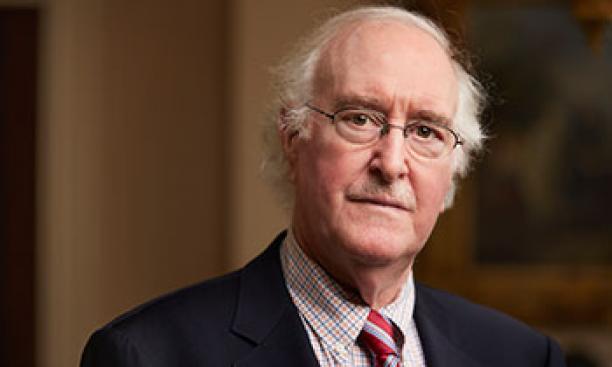

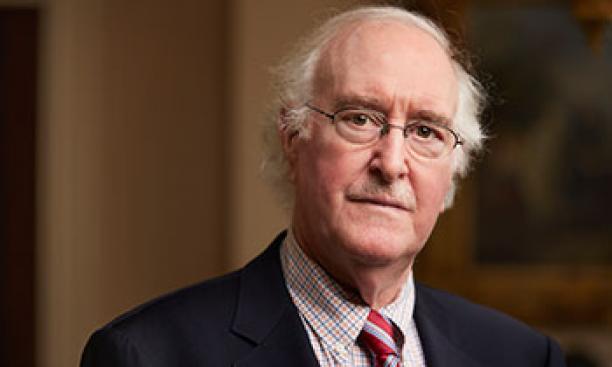

Jonathan Brown *64 is one of the most important art historians of the last 50 years. In books and exhibitions he has explored the work of Spanish Golden Age artists such as Velazquez, Ribera, and Zurburan in a rigorous yet approachable way and set it in a rich political and religious context. Brown offers a more personal view of his subject in his most recent book, In The Shadow of Velazquez, which is based on a series of lectures he delivered at the Prado Museum in Madrid in 2012.

Brown’s parents, Leonard and Jean, started buying art in the 1950s, when they acquired paintings by Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Willem De Kooning. As those men became art-world superstars with prices to match, the Browns moved on to collect documents and publications by the Surrealists and members of the Dada movement. After Leonard died, Jean focussed on the work of the Fluxus group and other “anti-artists” of the 1960s. She sold her collection to the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles in 1985.

Brown grew up surrounded by his parents’ growing collection, but his choice of career was determined by a year of study in Madrid while he was an undergraduate at Dartmouth. The city was only a generation removed from the civil war in which General Francisco Franco had seized power, and its university still showed the signs of the conflict, Brown remembers: “Buildings partially in ruins, bullet holes in the walls of structures that had remained standing, broken windows waiting to be replaced.” He was also struck by “the omnipresence of police officers; it was a vivid introduction to the machinery of a military dictatorship.”

During his time in Madrid, Brown fell in love with the works in the Prado and decided to pursue the study of Spanish art in graduate school. There were only three senior scholars then devoted to the subject in the United States and none at Princeton, where Brown nonetheless ended up because of the general strength of the department.

He stayed for 13 years, earning his Ph.D. in 1964 and staying on as an assistant professor until 1973, when he became the director of the Institute for Fine Arts in New York. Five years of administrative duty were enough for him, and he returned to teaching in 1978 with an ambitious goal: “to increase interest and knowledge of Spanish art in the English-speaking world.” He found a model in Wen Fong ’51 *58, a scholar of Chinese painting who helped push the field into the mainstream of American art history by publishing his own scholarship, training graduate students and organizing exhibitions and symposiums. “Mao Tse Tung was Francisco Franco writ large,” Brown writes. In both cases, the dictator’s death led to a more open society to which scholars had more access and in which Americans took a greater interest.

Brown’s study of Velazquez, published in 1986, remains a major academic work, as do his studies of patronage in Spanish art and of the Buen Retiro in Madrid, once the site of the royal palace and now the city’s most beautiful park. His students occupy important positions throughout the art world, among them Marcus Burke ’69, the senior curator at the Hispanic Society in New York, the most important center for the study of Spanish art outside of Spain. And Brown, who lives in Princeton and still keeps a carrel in Princeton’s art history library, has curated numerous exhibitions, including a show of Spanish drawings at New York’s Frick Museum in 2010 and 2011 along with Lisa Banner ’85.

None of that has dimmed his love of his subject, especially of the work of Velazquez. The master’s great painting Las Meninas reminded Brown of Jackson Pollock’s brushwork when he first saw it in 1958. He writes in a chapter on Velazquez’s stunning, enigmatic portrait of the Spanish royal family that he continues to be overwhelmed by the painting’s “undeniable magnetism.”