I’ve been thinking today about a basic question that we might pose of our various historians (thinking of all the writers we have read as in some sense historians): how like the past is the work they make; that is, how far does it attempt to imitate, in its form, the form of the past itself; does it make a model? Or is it, in its form, more accommodated to the present needs of the reader? Are Susan Howe’s collages a picture of what the past is really like, a picture more accurate than what the archive gives? (That is: is the past a kind of half-palimpsested crossword of ideology and experience, requiring perspectival rotation for even first-order legibility? Which may also be to say, is that what the present is like, or what that present was like?) Or, are the collages primarily designed to disrupt other representations, to allow us to hear voices and see relationships obscured by historical narration?—but not claiming to be like what the past was like, were we to have been in it?

The distinction gets slippery as I try to write it out—maybe it is roughly between ontology and epistemology? Maybe another way of putting the matter: when is a poetics of history directed to history (to historiography, writing about the past), and when is it directed to the past? Perhaps Howe’s work out of the archives is the most challenging instance of the problem so far. But you could ask: is Hegel’s dialectical mode like the history that it relates? (If the answer is yes, is that because his model for how history works is thinking?) And—I’m really thinking myself as I go here— have I accidentally displaced us from the question of historical consciousness? Are not these various writers modeling historical consciousness, rather than modeling the past? Again, Hegel basically identifies the two, yes? Howe’s collages: are they pictures of the past, or of the mind engaged with the past, managing its traces? Maybe more the latter?

So a revision to my question: how like the mind-thinking-history is the work of our historians? How much does it describe, how much does it model, historical consciousness? And what are you supposed to do with a historical consciousness, anyway? Think that way in the archive? Or all the time? (Can you have more than one—can you, do you, assume alternative consciousnesses as you read; is that why you do it?)

Maybe this line of questioning is provoked by a turn in the syllabus—I wondered near the end of class about the relation between linguistics and poetics as models of history, and that distinction seems more illuminating to me the more I think about it. The first half the class we travelled with Hayden White, who repeatedly invokes linguistic models for understanding historiography, grammar for classificatory and synchronic operations, syntax for dynamics of the historical field considered as process. He also, it should be said, thinks in terms of tropes, which cross from the vocabulary of rhetoric into the vocabulary of poetics—irony, metonymy, synecdoche, metaphor. But now we are in the territory of rhyme, a word Graham used to describe the various ways that sound hooks together words and phrases in Howe’s work. (And that we found ourselves using, too, when we talked about the kinds of resemblances and reminiscences that criss-cross the stories of Kluge’s Dispatches.) On rhyme, linguistics has no purchase; rhyme is no part of the deep grammar, and its relations to morphology are unsystematic. (I would think!—insofar as some rhymes arise from morphological patterns, but by no means all; e.g. “realistic” and “fragile birch stick”.) Which is to say that the basic syntax of agent, verb, object—the syntax of English subject-verb-object word order especially—has no authority. That exemption from causal logics at the sentence level, and from their higher level analogues, allows Howe to assemble or reassemble, to concatenate and to juxtapose, the past in different ways. Kluge’s defiance of historicism is narratological and imagistic, but his sentences are well-formed. Howe carries her query down below the sentence to the level of word and phrase; what’s more, she jumbles their spatial relationship on the page, so questions of their priority and orientation become endlessly arguable. The sentence is no longer available as a model either of historical process or of thinking the past. (Maybe Robin Coste Lewis is after the problem at the same level—though the title may be more important to her than the sentence.)

Well: all to say, we begin to see why “poetics of history” might be a liberating phase, insofar as it permits a series of relations—on scales small and large—uncomprehended by linguistics and perhaps even by rhetoric. (And if syntax is basically beholden to causal logic, rhetoric is similarly dedicated to persuasion; whereas poetry, they say, “makes nothing happen.”)

Just a few words on sound; I loved Fedor’s characterization of it as an instrument of inquiry; and likewise Graham’s sense that the recognition of something like historical truth, or presence, or discovery in the archive, might have the same feel as getting a line right. Worth saying perhaps that the kinds of sonic affinities that lead Howe from word to word and phrase to phrase are not part of the received history of etymology; they are instead more accidental; you might say free-associative, except that what you get is not fluent in the manner of a “stream of consciousness,” but jagged, interruptive, self-interrogating, restless. Listening to the archive in this manner is certainly perverse. (Aren’t archives the quietest of all places?) But these sonic connections defy equally the narrative order of historiography and the filing systems of the archive itself. Perhaps they are therefore the past more raw than we could otherwise get it. Is that because sound is itself some kind of key—that it discloses patterns audible no other way; that it is a hidden principle of what Jameson would call “the political unconscious”? Or because we need some alternative principle, and for poetry, sound is ready to hand, to ear?—one possible mode of recombination, without special privilege. I don’t know.

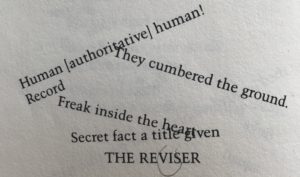

I’ll conclude by posting our own attempts at Howe’s method—ah, I see Graham already has; this post comes hard on his heels!—and with a residual question, how much these poems disclose to interpretation—whether there is a kind of understanding that resides between large claims about method, of the sort I have been making, and the most local attention to sonic affinity. Perhaps as close as we got was Jeewon’s sense of the final poem as a dynamic picture of the lines drifting and settling, too and fro, like a leaf…

…and how that settling brings us to that polyvalent line, “THE REVISER,” flat at the bottom; is that as much as to say, start again? Re-see? Or does it reflect a trajectory from a catastrophe (“cumbered the ground”), to its affective reception, that freak in the heart, to its titling or naming, to a historical proclamation that can only be a revision of whatever happened? For good or ill? (Is “THE REVISER” the title? And if so, who is the author?)