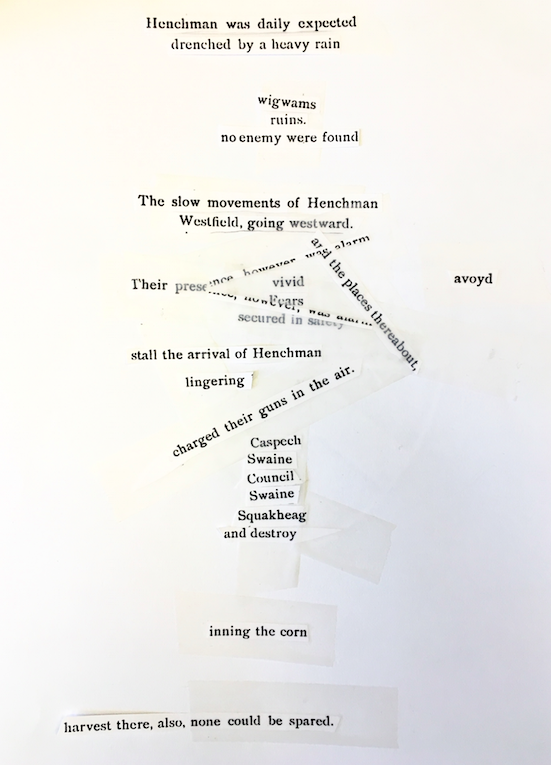

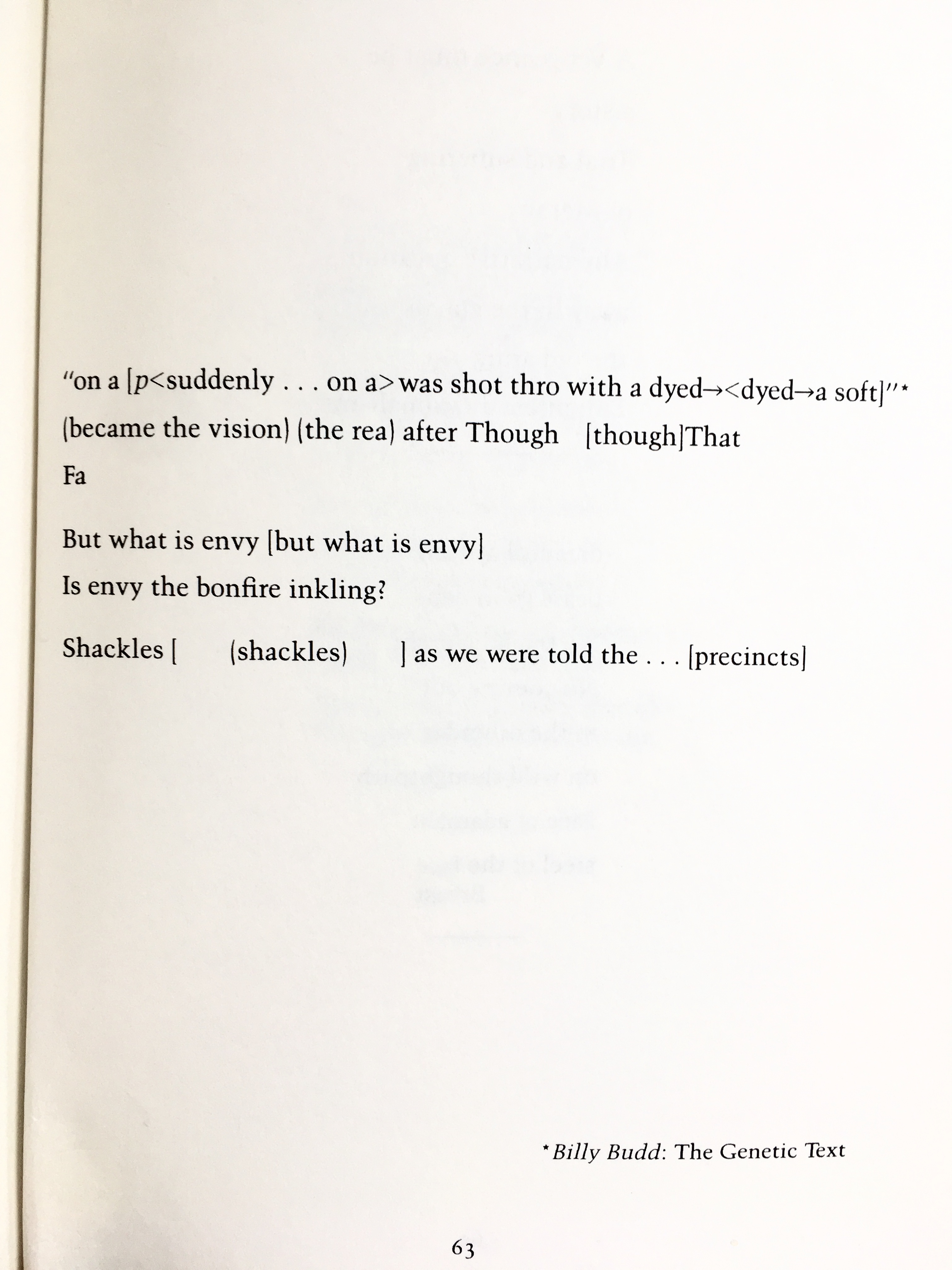

In we went — directly. And this was where we started:

We probably spent close to half an hour trying to get those words into our mouths and into our minds. A central concern was how to “voice” such a poetic proposition. And we made the round through various tactics, technics, and intertextual references. Reading the spaces as forceful silences created undeniable effects. Reading the poem against its own posited order (i.e., from the bottom up, or simply reading around in it) could feel like a participatory activation of its gestures of syntactic transgression. One could read the unusual punctuation explicitly (by naming the signs), implicitly (by musical or oratorical intonings), or even go full Victor Borge (which Dolven pulled off in fine style).

There was, of course, the question of what all of this was supposed to mean — those words on that page.

Most suggestive, the page, taken as a whole.

Like all of the Howe, the language certainly created a mood. But could it be glossed? Could it be paraphrased?

We thought about Anne Carson and her “bracket” translations of Sappho. There, the stuttering square-parentheses bespeak the lacunae. Here, the citation of the technical notation for the transcription of the (multiply-overwritten) manuscript of Melville’s anguished tale (of strangulated silence, injustice, and violence) certainly seems to signal that we should be concerned about what cannot be articulated. That made me what to go here:

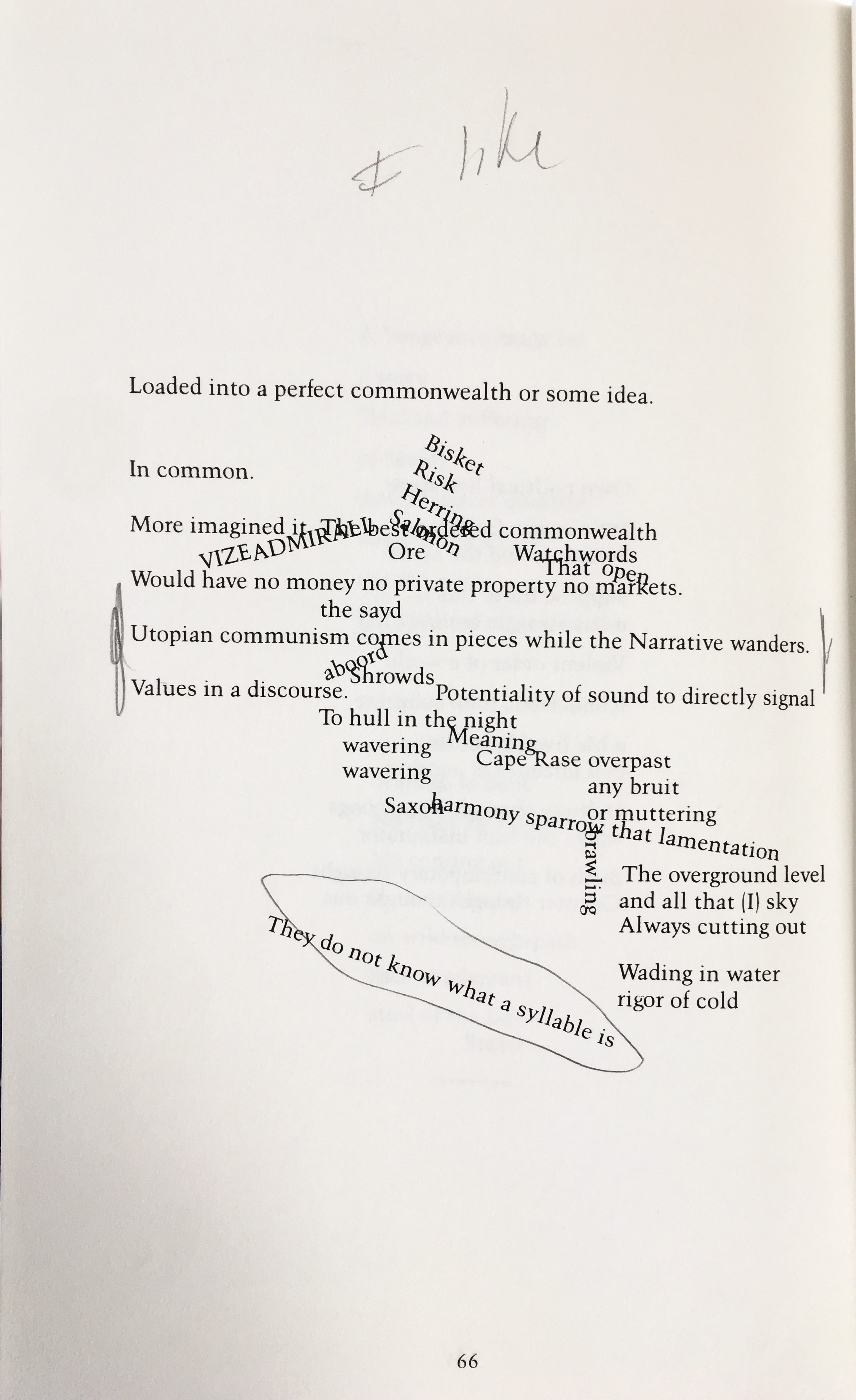

But sage Dr. Dolven wisely directed us over this way instead:

Again, we spent some time just saying this poem out loud in different ways.

It was in the course of experimenting with more and less “expressive” oral renditions of this poem that we came to rest on what became an important problem for us in thinking about Howe’s works this week: exactly how “present” was the “author” in these poems?

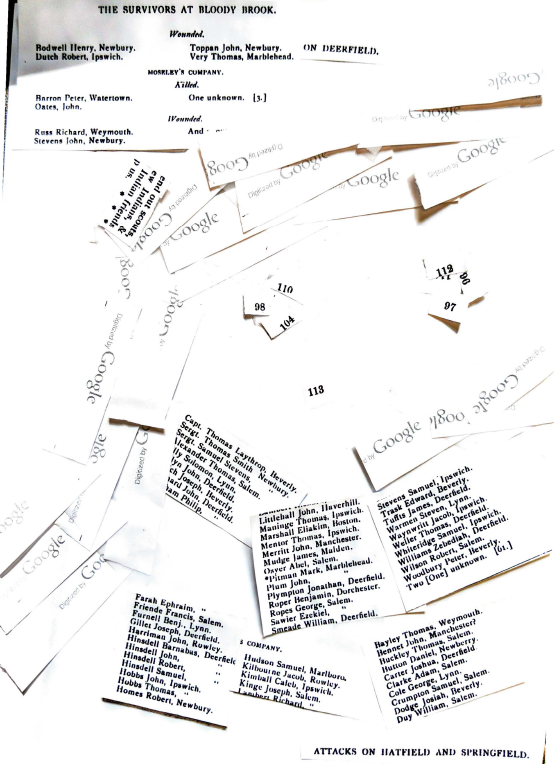

Which is to say, are we to “feel” a specific human doing the work of expression/articulation in these lines and in these pages? Or would we do better to encounter these fragmentary, automatic, recalcitrant shards of language as something like a raking of the archives — a gleaning? Are we in the presence of the coughed-up bits of history itself (flotsam, blown into the gutter of this volume by the winds of time), or in the presence of an actual glossolalist, who is regarding us with longing eyes as every attempt to communicate produces a torrent of knotty, aphasic incomprehensibles?

It felt like it mattered a lot which way you broke on this. Yes, any given page could be read either way. But which way did the work as a whole, the work of Singularities, want to be read? A principled judgement on all this must, I think we agreed, reckon with this moment and the author-presence/author-disavowal it enacts:

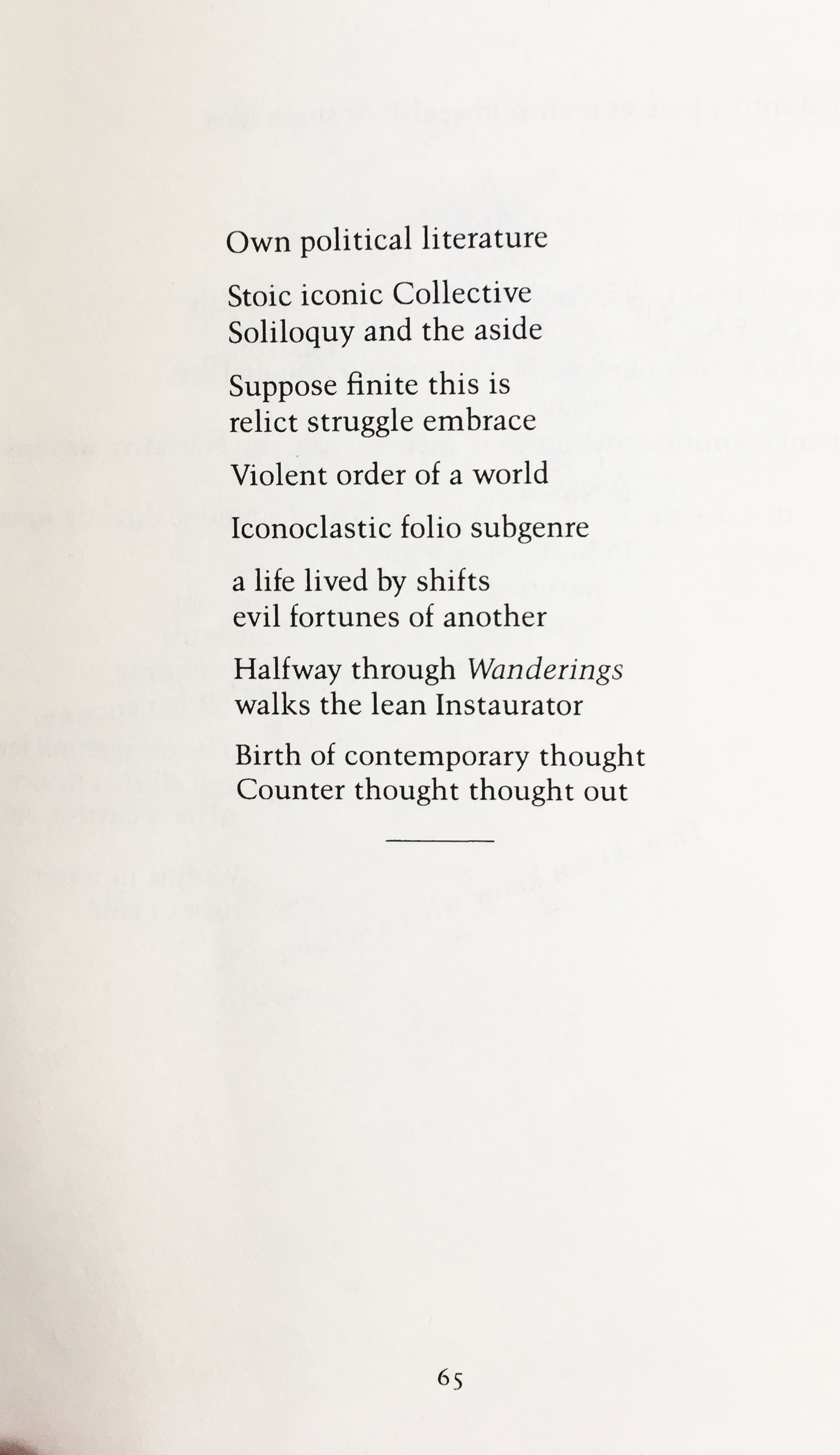

Authorship. The question took us to another poem (but wait, is this a “poem?” We spent a good deal of time talking about the poetic units into which this volume is sectioned) that repeatedly intoned its own version of what might be called “the author problem”:

“I stretch out my arms / to the author” — I must say, I really love this moment. Yes, asking it to shoulder the heavy burden of the intersubjective ambition of Howe´s oeuvre is asking too much, but if someone in the throes of a glossolalic catatonia looked at me with longing eyes as she stammered in the archive’s alien tongue, stretching out my arms to her, is, I think, exactly what I would want to do…

Except, maybe, if she made it clear that that wasn’t what she wanted. And then, I think the next thing I would try attempt would be to try to sing along.

And this is a reference to what I offered as my own “reading” of Howe — my own sense of the work that these poems can do, and the world I felt them trying to articulate.

My first efforts to read Singularities came to little. I lay in bed and read the poems silently. And I couldn’t make much sense of them. I was pretty bored. I took the little volume with me for a few days, and dipped into it here and there (e.g., sitting by myself at a loud sushi bar downtown on a Friday night) to no effect.

I tried reading a few of them with my daughters, though, before bed. And that was interesting. Because then we had to say them out loud. And we had to make decisions (in the ones that are laid out as bomb-shard poésie concrète) about what line to read when, giving the enterprise of saying them a bit of performative verve. It made me realize that my facility for “hearing” the acoustics of a silently read poem isn’t really very well developed. I needed to read them out loud to hear them. And these were poems that really needed to be read aloud.

So I started back at the beginning, and read the whole book again. Wandering back and forth outside (so as not to annoy everyone in the apartment, as they soon tired of my ravings).

But the act of wandering and SAYING every one of Howe’s words gradually gave me a very strong sense of intimacy with “her” (a sense of intimacy with the author; as sense of, as I say, singing along with her). Before long, I was wholly persuaded that this was what these poems wanted more than anything else. They wanted to be felt in the mouth. And that the “grace” or sense of “communion” that they sought (or is it that they merely “posit”) is to be found in this convergence of tongues.

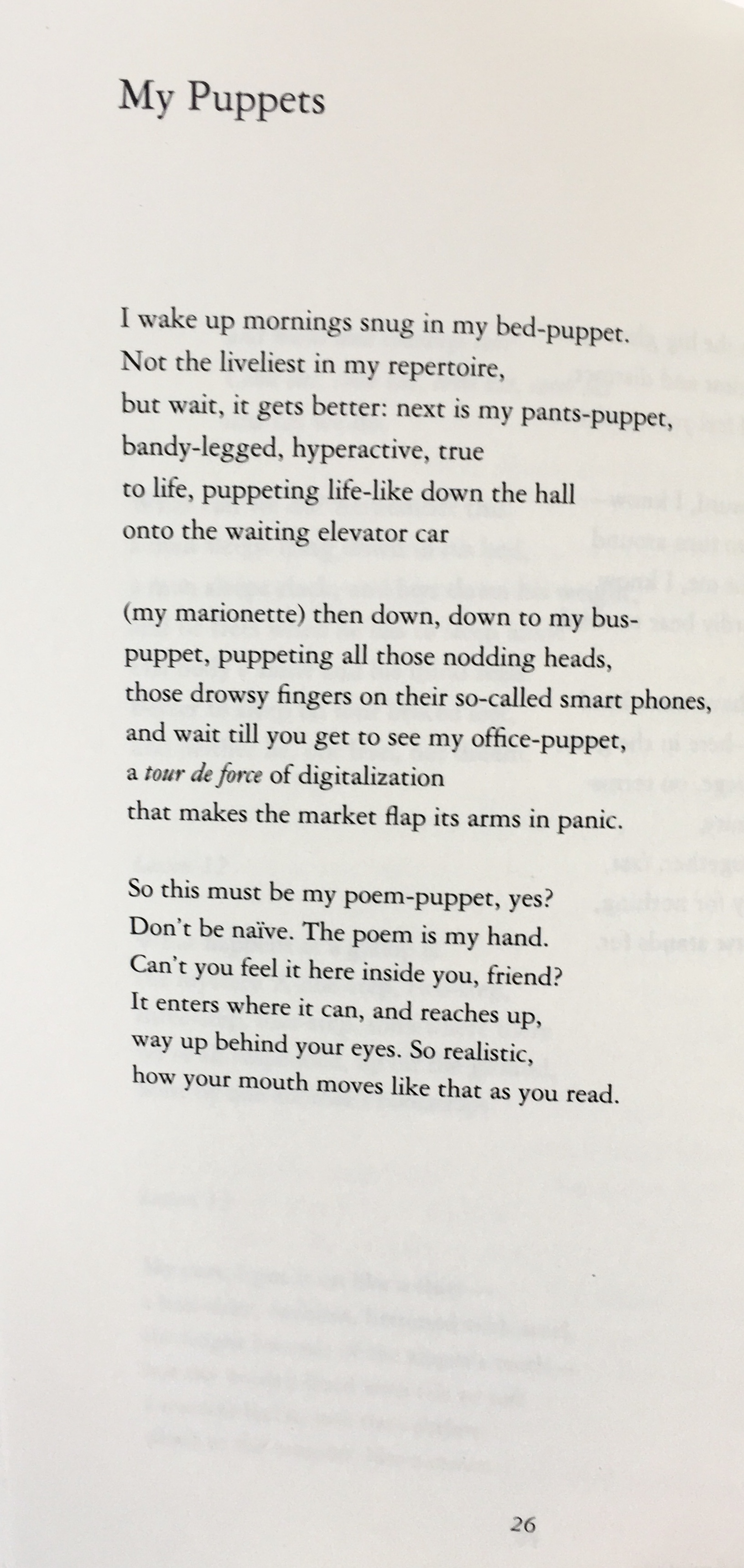

It is possible that my feeling for this queer secret-sharing via voice must be passed through one of Dolven’s own poems (from Speculative Music)— one that I admire:

I will confess that I find this version of the intimacy in question rather sinister. And possibly properly perverse. But that doesn’t mean that I cannot conjure my own redemptive version thereof.

And, with my quick-draw, hair-trigger on the general issue of the redemptive, I may have done just that with the Howe: reading the poems aloud, pacing, I found myself increasingly certain I was “realizing” their power/force/ambition/hope. Yes, you can read two very different senses of “realize” at work in that last sentence…

Right. Well, I am a kind of “serial understander.” (And I mean that in a [somewhat] pejorative way; I know many thinkers who resist understanding longer and more effectively than I do — and to richer effect). So there you go. My understanding. Predictably enough, another epiphanic communion. Parachute me in just about anywhere, and I’ll get you one of those.

[visualize old-school colon-and-parenthesis smile emoji]

*

Still, I do not think that I am totally off base in relation to Howe.

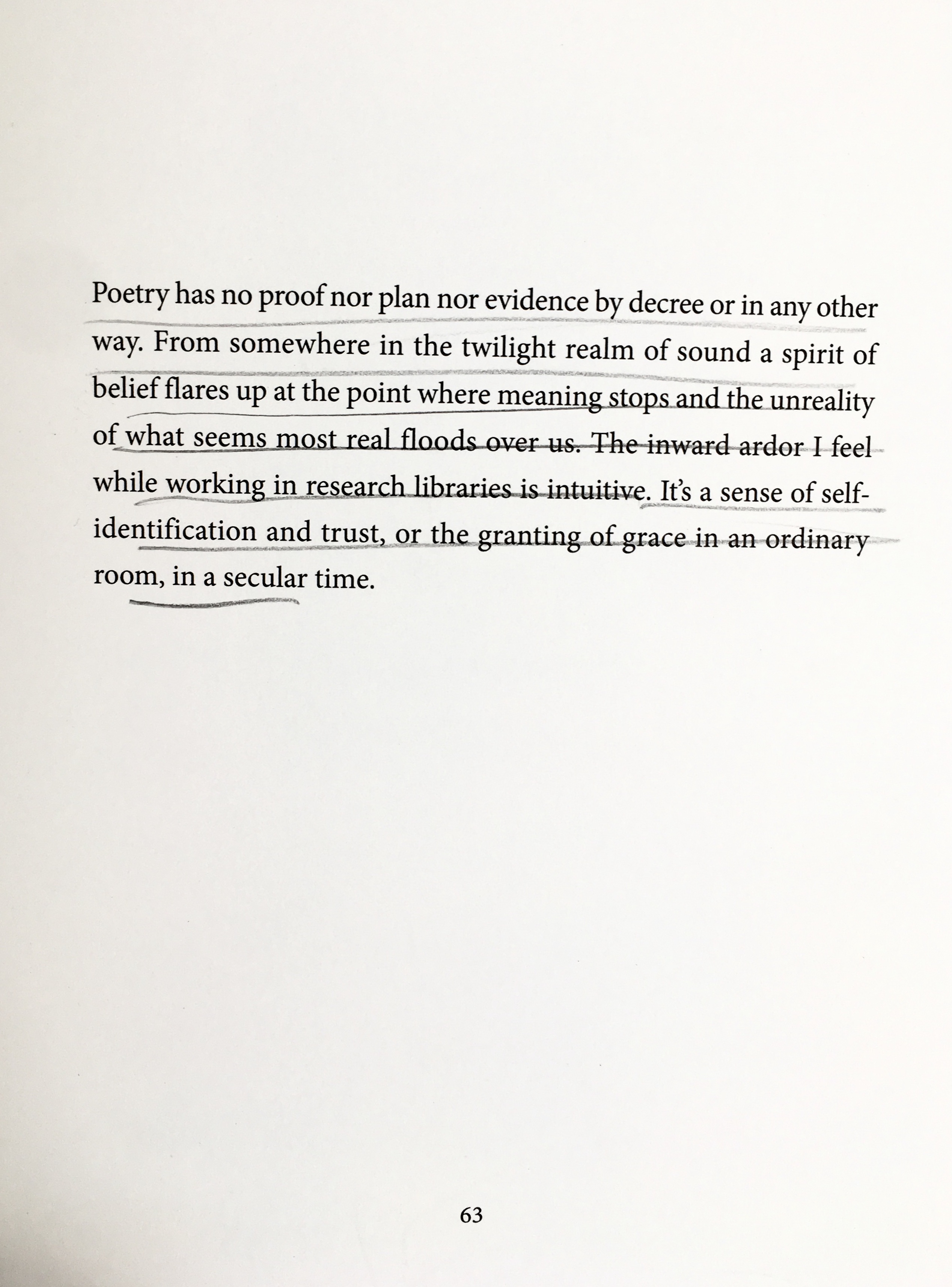

Take this, for instance, this extraordinary moment in Spontaneous Particulars (from which I launched my punctum exercise this week):

Such an amazing proposition. One I think every “card-carrying” historian should print out on a wallet-sized slip and carry about on his or her person at all times.

What would it be to experience (and dignify) an intuition of the historical within an archive, or while working with a source — an intuition conformal with the poet’s upflaming certainty that a given sound-proposition opened way the to real-beyond-the-real?

Ahhh, now we are genuinely touching the hem of the suprahistorical. No?

And if I read Howe right, she is here offering us an intimation of a genuine “poetics of history,” one shot through with an exquisite humility before the mystifying power of secular “grace.”

I was left thinking of the overwhelmingly affecting (for me, anyway) way that Michael Fried wends his querulous way (in “Art and Objecthood”) from Perry Miller on Jonathan Edwards’s preoccupation with the ecstatic eternity of every moment to his own heart-stinging cry for secular grace (in/through art): “Presentness” Fried tells us, in the memorable last line of his essay, “is grace.”

And history, transformed into a gust of “presentness” is exactly the grace I read Howe (who has some commerce with Jonathan Edwards herself) invoking.

And, further, I think her work opens onto exactly that gift.

Here was the image we sketched on the board as we thought our way through all of this:

*

All of this feels abundantly significant in the context of our course. Among other things, it suggests (and we discussed this) that we may have reached an escape velocity vis-à-vis Hayden White’s gravitational field. After all, White’s powerful account of the linguistic prefiguration of the historical field was precisely that — linguistic. But beyond linguistics lies poetics. Linguistics cannot tell you anything about rhyme, say. But what we are talking about in what I take Howe to be saying is exactly something like historical rhyme. Can we imagine what that might be? Can we move into the archive looking for these? Ready to sense these? And when we are graced with the sudden intuition, prompted by the logics beyond logic, that the archive is disclosing one of its “rhymes” — one of those moments that permits the unreality of what seems most real to flood over us — what can we do to be faithful to such occasions?

(We will do well, I think, to consider Sebald’s Vertigo, this upcoming week, as a possible answer to this problematic. Is all of Sebald’s “fiction” precisely an effort to answer this last question?)

*

It is important, I think, to get a word or two in here about a healthy moment of resistance to some of this that happened in the seminar. Greg was, I think, really onto something when he expressed a (respectful) sense of what I might call the “datedness” of Howe’s posture with respect to the archive (specifically), and maybe history itself (more generally). After all, as Greg put it, he doesn’t experience the work with “his” archive as a kind of hermetic withdrawal into the Beinecke-tomb for communing with the spirits through the contaminating red-dust, etc. (e.g., “Downstairs, in the Modernist reading room I hear the purr of the air filtration system, the rippling sound of pages turning…” SP, p. 43). He just opens his laptop. In bed or wherever. And he is in exactly no less communication with everyone in his life under those circumstances. I completely feel the rightness of this. Because this is mostly my archive life now too, and I have lived across the watershed of these two worlds. My trip to the archive to do my punctum exercise this week was the first time I had been in one of those spaces in six or seven years. But I have written a significant amount of history in that period, plenty of it drawing on archival materials.

So in the end, I am still weighing my sense of all this. The Howe is clearly something other than nostalgic. But holding Spontaneous Particulars next to Dispatches from a Moment of Calm — or, for that matter, next to H & O — can lead to a feeling that the Howe is in some sense more genuinely retrospective.

*

There is more to say. We spent a good deal of time doing our set of “exercises,” and I am going to drop a few of these in here:

Spring was in the air, in much of this. In the sense that a spirit of fun crept in the open windows with the warm breeze — the same one that was scattering the petals of the magnolia blossoms so wantonly in the courtyard. I’ll pass over an effort to summarize what came of our hand-and-thought craft on these, and what came of our efforts to reflect on that conjunction.

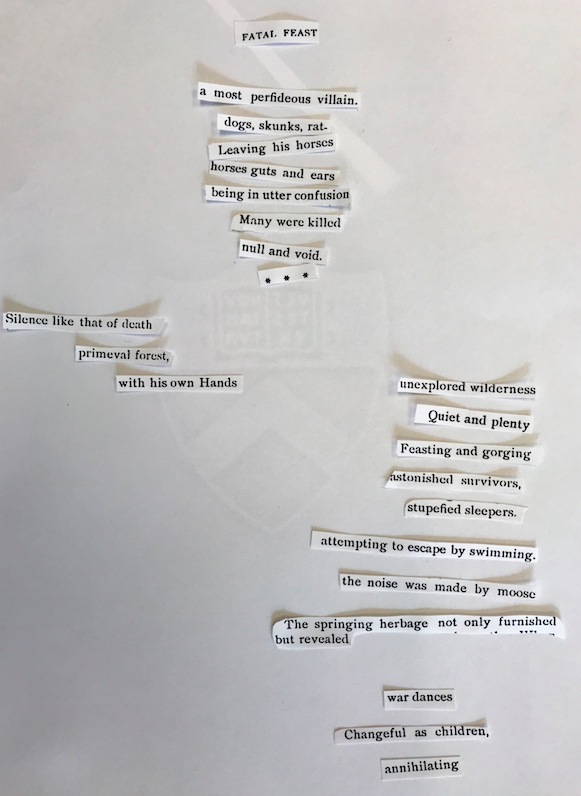

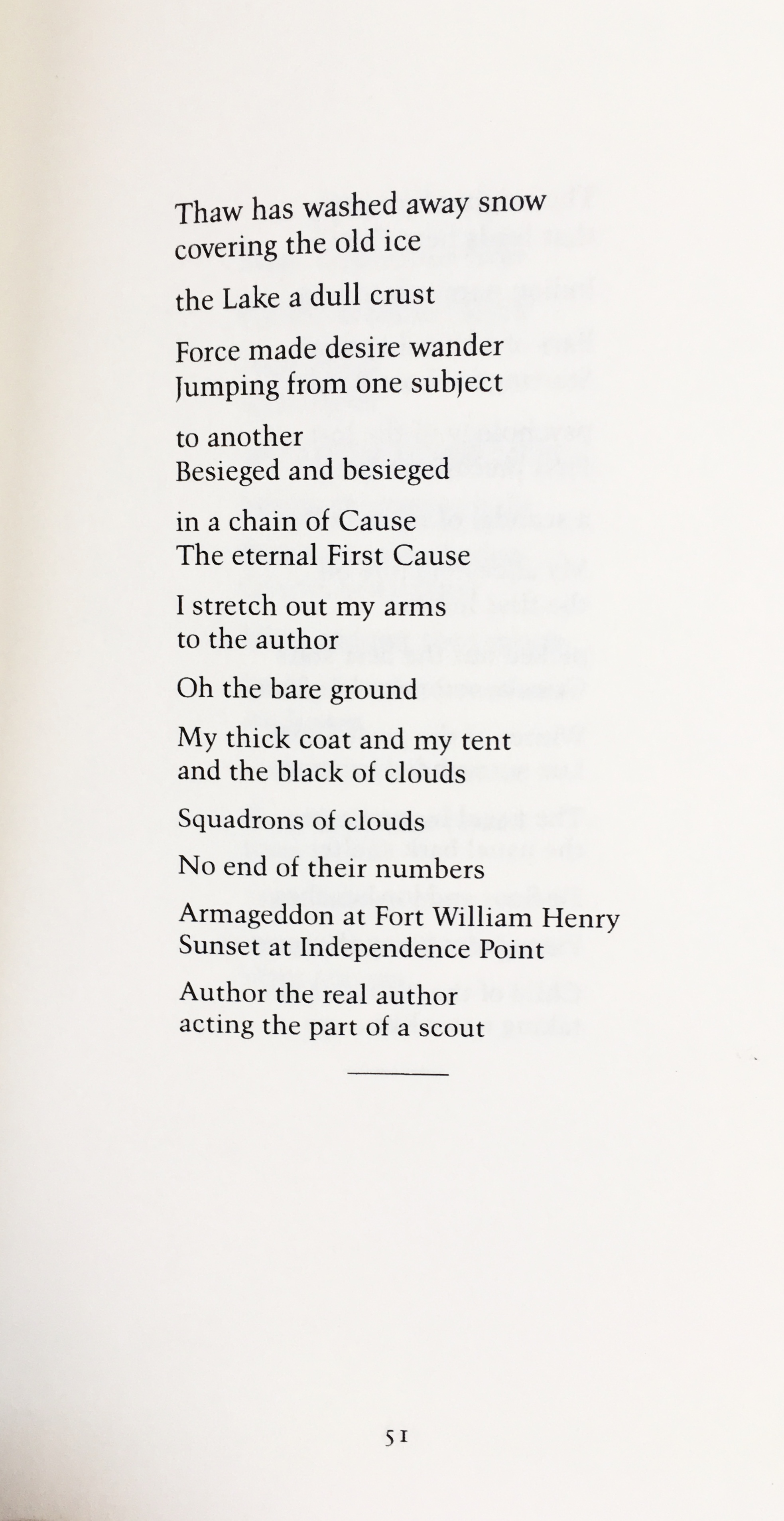

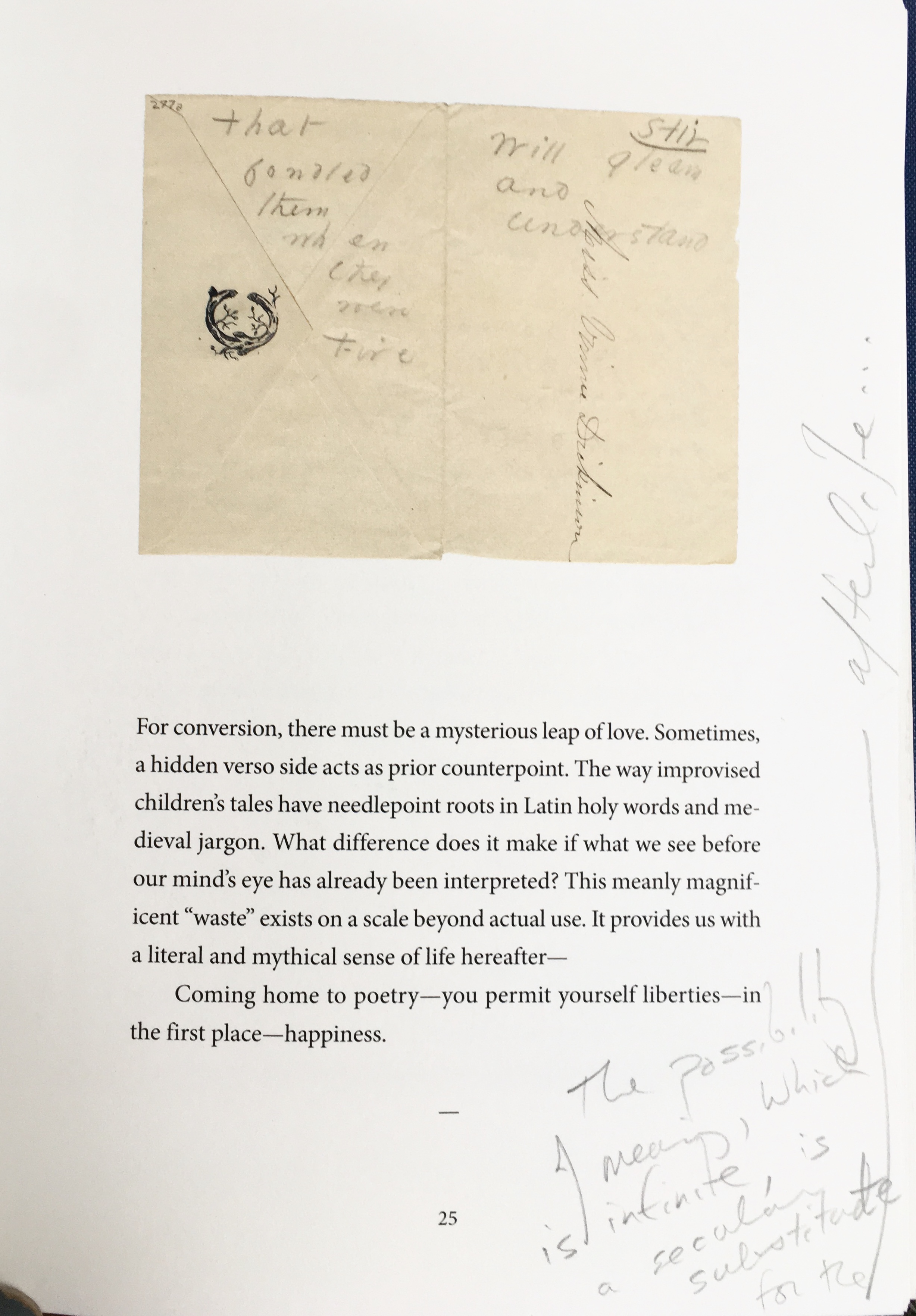

Instead, I’ll end where we did, on love, and the page of the Howe where James left us:

The infinite possibility of meaning, as a kind of metaphysical dilapidation of paradise. Sense and sense are the same word for such different things.

“For conversion, there must be a mysterious leap of love.”

Indeed.

– Graham