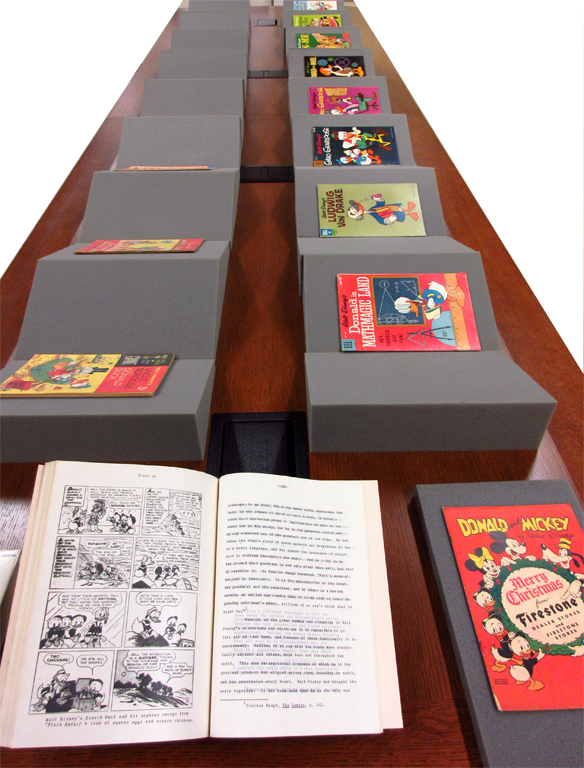

An exhibition of the comics collection and senior thesis of William Johnson Jones, Jr. ’57. The thesis, Comic Books, opens to a reproduction of comic strips featuring Donald Duck and his three nephews.

The Department of Rare Books and Special Collections welcomed members of the Class of 1957, who were back in Princeton for a formidable 60th Reunion last week, with an exhibition of comic books dated from the 1940s and 1950s. Selected from a donation made by William Johnson Jones, Jr. ’57 to Princeton, these paperback funnies embody the passion of a youthful comics reader and collector, and the independent mind of a student-scholar who disagreed with authority opinions.

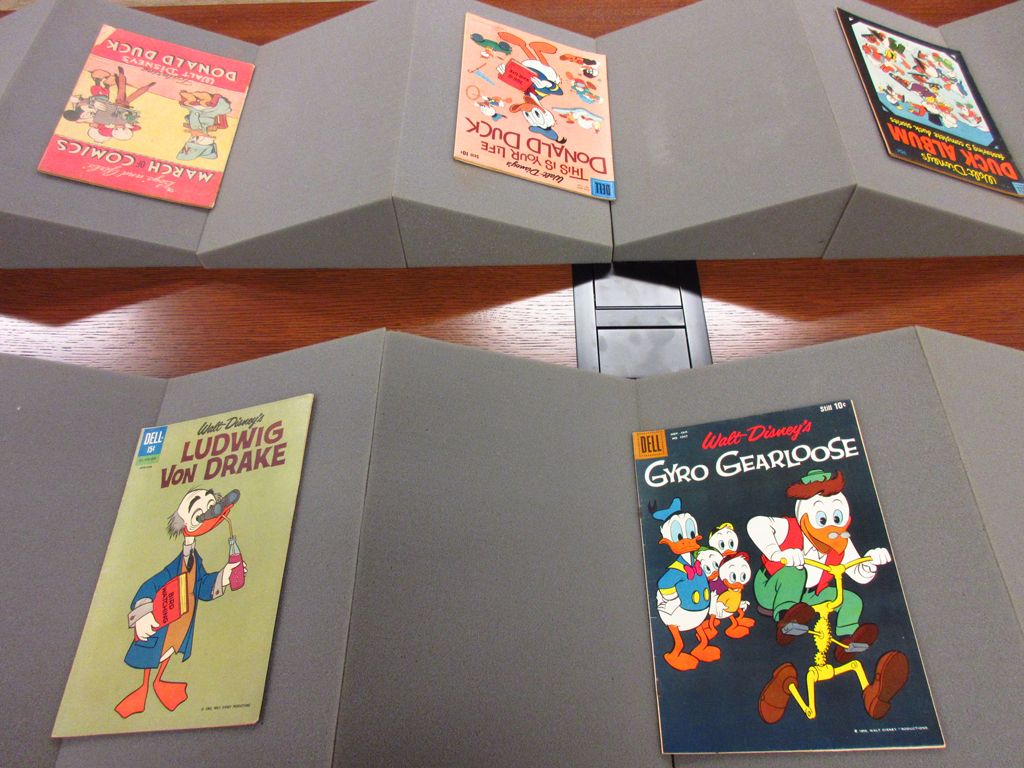

Walt Disney’s comic magazines and books dated from the 1940s and 1950s, collected by William Johnson Jones, Jr. ’57 for his thesis research and donated to the Department of Rare Books and Special Collections in 1998.

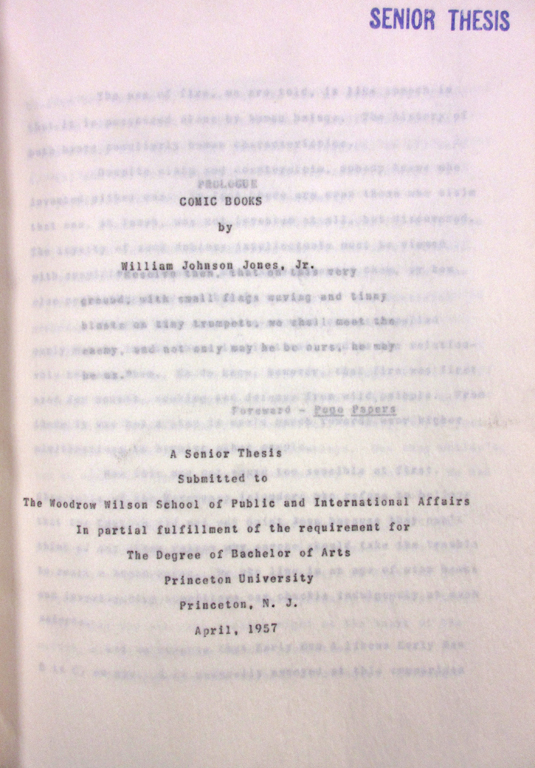

For his senior thesis, Comic Books, Mr. Jones examined a controversial format of reading materials—comic books. By the time he finished his typewritten manuscript in 1957, an anti-comics movement had successfully put crippling restrictions on the industry, based on widespread public concern about “the deleterious purported effects” that comics had on young readers (Tilley 384). It wasn’t until three decades later that comics would begin its slow climb back up towards mainstream acceptance and even appreciation, when Art Spiegelman used the powerful visual narrative to relate his bleeding Jewish family history in Maus: A Survivor’s Tale (1986), one that is allegorically disguised as a story of helpless mice and menacing cats.

Comic Books, a senior thesis submitted by William Johnson Jones, Jr. to Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, Princeton University in 1957. (Mudd Manuscript Library, AC102)

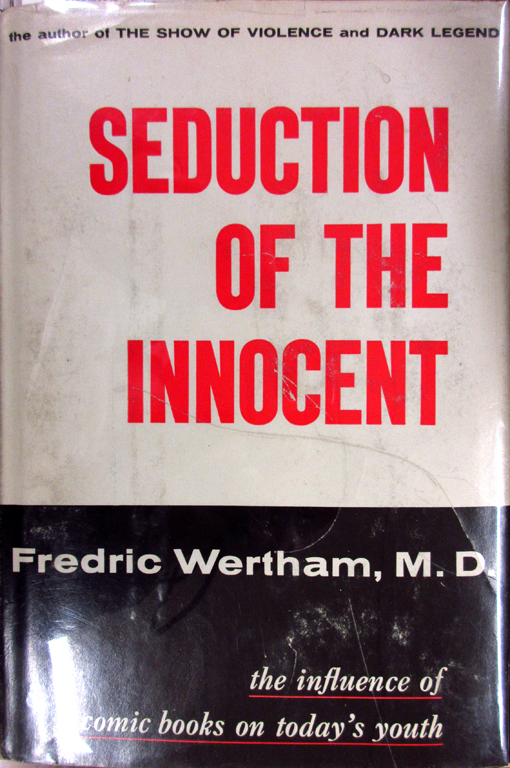

Jones, however, decided to investigate the validity of accusations piled upon comics in his senior paper. Read sixty years after its completion, the undergraduate writer’s lucid analysis, scientific reasoning, and common sense argument stand strong in what can almost be seen as a prescient defense of comics. Jones was not afraid of taking on Fredric Wertham, a psychiatrist who treated children identified as juvenile delinquents in New York City and the central figure of the anti-comics crusade. Wertham’s influential book, Seduction of the Innocent (1954), claims that through his personal clinical research with young people he found a causal relationship between reading what he broadly defined as crime comics and juvenile delinquency. His testimony on the harm of the format is thought to be hugely responsible for bringing about the restrictive editorial code imposed on comics publishing and eventually the decline of the industry in the 1950s (Tilley 385).

Fredric Wertham’s Seduction of the Innocent: The Influence of Comic Books on Today’s Youth. New York: Rinehart, [1954]. (Rare Books, 2010-0836N)

We hear a youthful, defiant voice in Jone’s self-conscious challenge he was going to bring against a popular authority figure:

That a serious refutation of Dr. Wertham’s position would be necessary was at first considered ridiculous to me, and I’m sure would still be considered ridiculous by most children’s who, if they want to know what comic books are like, read, not Dr. Wertham, but comic books. But grown-ups seem to be very easily impressed by things that come in hard covers, so this defense is undertaken in deference, not to the soundness, but rather to the popularity, of Wertham’s position. (Jones 41)

To be sure, the incendiary, if well-meaning, psychiatrist was not without contemporaneous detractors. Jones was able to locate robust criticism in a paper titled “The Comics and Delinquency: Cause or Scapegoat” by an NYU education professor named Frederic M. Thrasher and quoted him at length. Thrasher pointed out the lack of rigorous sampling and control in the kind of research published by Wertham, the conflation of correlation with causality, and statements that were asserted without the support of research data (198-203).

It is impressive that, as part of his thesis research, Jones apparently managed to get in touch with Wertham and sought direct response to his inquiry. “He [Wertham] recently told me that, ‘In my opinion comic books have no rightful place in either art or literature.’ ” Jones reported (35).

The thesis shines where Jones’ assessment of comics is empowered by persuasive reasoning and enriched by his sensitivity to social issues. On the sweeping condemnation of comics, he provided a common sense reminder:

The comic strip is just a medium. This may seem too obvious to mention, but it is amazing how often it is forgotten…

Comic books have the distinction of being probably the only medium to be judged, not by their best, but by their worst. Nobody would think of condemning painting because most paintings are bad paintings, or the novel because most novels are awful, but they are only too ready to apply this logic to the comics. (Jones 111)

What really concerned Jones in American comic books was stereotypical depiction of nonwhite characters–“[N]egroes, [J]ews, foreign born. etc.”–which he ranked as “the most serious issue the industry had to contend,” citing antagonistic foreign and racial relations as negative consequences (39-40).

If Jones has made points that seemed to have stood the test of time reasonably well, his refutation of Wertham’s assertions will be appreciated even more deeply in the context of updated understanding of the psychiatrist’s anti-comics work. When the embargo of Wertham’s personal papers at the Library of Congress expired in 2010, comics researcher Carol Tilley, a professor of library of information science at the University of Illinois, made an early excursion into the psychiatrist’s daunting amount of archive, with astounding discoveries. By comparing Wertham’s case notes with young people he had treated and what was printed in Seduction of the Innocent, Tilley documented how Wertham manipulated, overstated, compromised, and fabricated evidence for rhetorical gain, reaching unsupported conclusions about the detrimental effects of comics on young readers’ ethical development and mental health (383).

Whether or not Jones has drawn intuition, confidence, and strength in his thesis research from having been a veteran comics reader (and simultaneously a high-achiever as opposed to a juvenile delinquent), or his firm grasp of scientific methods, or youthful daringness, or a combination of all of those, he has produced a distinct thesis that is worth re-reading at the ripe age of sixty years.

References

Jones, Jr., William Johnson. “Comic Books.” Princeton University, 1957.

Thrasher, Frederic M. “The Comics and Delinquency: Cause or Scapegoat.” The Journal of Educational Sociology 23.4 (1949): 195-205.

Tilley, Carol L. “Seducing the Innocent: Fredric Wertham and the Falsifications that Helped Condemn Comics.” Information & Culture 47.4 (2012): 383-413.

(Posted by Minjie Chen, East Asian Project Cataloger, Cotsen Children’s Library.)

Thanks for the comic book post!I’d say Mr Jones is spot on . Reading comic books provided some of the best entertainment I had during WWII. As Jones discovered reading was one of the few pastimes available to the sick! Dr Wertheimer probably believed along with many physicians. As late as the 1960s that immobilization was curative.As a ( now retired) neurosurgeon I learned by the 1970s that rapid postop mobilization prevented numerous complications.My overall education was improved by”Classic Comics” which at least made me aware of the existence of some fine literature long before Princeton matriculation.