Well, it’s the last blog post that will be posted on blogs.princeton.edu/sisn/ forever.

So I guess it’s only fitting for me to start where I began.

Let’s look at what Facebook has become — not what it is, but what it means to us as humans and what it means to as a society. Facebook is not simply a social network, it is The Social Network, with capital letters. It is much more than the sum of its parts – more than just Profiles and Wall Posts and Pictures and Likes and Pokes. It has become almost necessary in society and has become an expected staple of our lives. If all of Facebook’s servers were to suddenly blow up and Facebook were to vanish, I’m pretty sure that the world would just fall apart. This is why I joined the class.

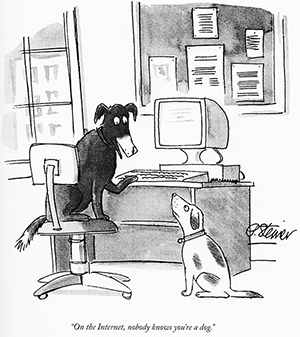

Because Facebook has finally succeeded where traditional forms of communication like mail or phones have not: it has succeeding in connecting us in something greater without depending on the real world. Before, you could talk to people through a variety of mediums. You could mail someone, and send physical object from one person to another. You could call someone, bridging miles or even thousands of miles instantly. There even was this new emerging technology found in the World Wide Web and email. But the problem with these forms of communication was that it was relationship-based. In other words, it was a conversation between two people, not a recreation of a group of people interaction, not of a society.

Sure, there were many attempts to try to raise societies in the communications world. There were forums, imageboards, forwarded emails, Myspace, Xanga, IRC, newgroups, and listservs. But outside of certain localized communities such as certain gaming communities, they never accurately created a society. There was never one single form of communication that could connect many people from many places. Take forums for example. Like Facebook, it has a bunch of people together on a site discussing and taking and fighting and joking around. But it was more like a conference call than a society.

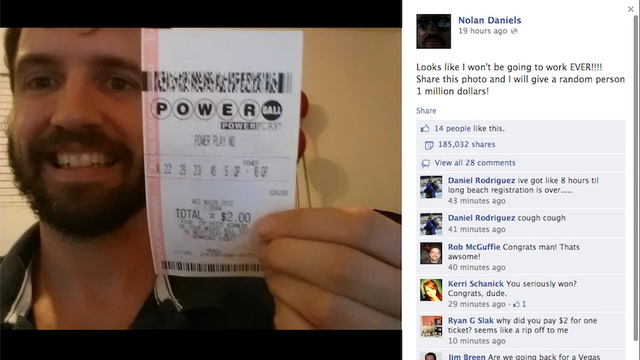

The difference Facebook had was that it plunged you into the flurry of activity from friends, family, and acquaintances. All you have to do is type “www.facebook.com” in the url bar and hit enter and you enter a virtual world where interactions between the people you know flow around you. People interacted with each other now, able to declare things to the world with status, express their likes with “likes”, and talk to each other.

Whether by intention or by accident, Facebook’s connecting power has changed our world forever. We see other communities such as Twitter and Reddit spring up, creating communities of their own. We even see attempts to emulate Facebook’s connecting power in other realms as the buzz word “social” visits every intellectual corner known to humankind. Video games today must have a social aspect. New web startups try to incorporate “social” into everything they do. Even site such as Grockit tries its hardest to be social and create a community centered around standardized test prep.

And on top of all of the common rabble stands Facebook, the originator and the most powerful and most encompassing social network. And because it revolutionized modern society, it hold a certain responsibility to the society it helped shape. And it was this responsibility we looked at in class.

You know, I could go ahead and begin to look at everything we learned this semester and explicate all of our blog posts and readings and ignite presentations. But who am I kidding. How could I ever cover a semester of work along with last flood of information from all of you, my peers? I would have to talk about Facebook experiments, about federal policy, about gamification, about the Facebook IPO, about good app design, about RenRen, about a million more bits of information. What we have learned has gone beyond what a mere 500 words can express, especially when I’m already approaching 700.

So I leave this here, as a note of endings.

This blog was the work of FRS 101, under the guidance of our two awesome mentors, Professor Ed Felten and Stephen Schultze.

Thank you.