Surrealist Film Themes: The Unconscious

For the surrealist, the unconscious is where lies the true key to life. When Breton writes, in his Manifesto of Surrealism, that existence is elsewhere, he means that that it is in the unconscious. He contends throughout the book that the current state of living only inhibits creativity and impedes access to the unconscious which he often times associates with femininity. He believes that this unknown, if accessed can provide a sort of enlightenment, a higher, more sense-based existence. The ability to easily transition between a dream-like state and reality, to be creative, and to appreciate everything as if one were a child seeing everything for the first time, this he contents is freedom, this is living and one can only truly live through the unconscious.

Accessing the unconscious means eliminating the barriers, which separate it from the conscious. This means forfeiting control, which is no simple task. It seems that among the many things inhibiting people from an existence worth of living is the way we interact with imagination. Breton writes: “To reduce the imagination to a state of slavery-even though it would mean the elimination of what is commonly called happiness-is to betray all sense of justice within oneself”. By limiting the imagination and living confined to only one way of thought, the unconscious is ignored, it becomes “darkness” simply because it is unexplored. Everything that is not seen as productive is thereby seen as worthless. The imagination is reduced to a sense of slavery because people then only try to use it as a means to conform to the needs of society—this perversion of the imagination, Breton argues only shows the desperate need to connect with the unconscious and confront a new possibility for existence. One in which feelings—sensations—are experience fully and where people do not limit themselves to experiencing only the “classifiable” (Breton 9).

Breton turns to dreams as a way to understand the unconscious, and he greatly implements Freud’s research although he changes it to match the intentions of the surrealist movement. Freud expresses, in his early research about unconscious and dreams that one can witness the manifestation of the unconscious in dreams. He speaks of condensation and displacement, symbols and other factors that can be used for the interpretation of dreams. While Freud used dream analysis as a way to remedy neurosis, the surrealist would like to use it as a way to plunge into a world of uninhibited sensation, into a world in which people do not need to act but instead, are simply receivers of actions. As he indicates, “the mind of the man who dreams is fully satisfied by what happens to him…” (Breton 13). Such a man is entirely immersed in the environment and by not focusing on controlling, by simply allowing his senses to be stimulated; he is able to let himself be carried along. The surrealist thought that such immersion and vulnerability to the unknown parts of oneself and the sensations it could produce was the way to begin to access the unconscious and to allow its effect to impact the way of perceiving the world.

The focus on the unconscious as the key to a higher self and its association with what the surrealist describe as the feminine self suggests that the surrealist are challenging a patriarchal society and way of thought. Their belief in the importance of the unconscious is a reflection of their desire to focus less on controlling and more on understanding themselves. This is eventually reflected in their creations, particularly in their films.

Breton, Andre. Manifestoes of Surrealism. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan, 1969. Print.

Surrealist Film Themes: Vision

Figure 1 — A blind man kicked aside in Buñuel’s L’age d’or.

From Dalí and Buñuel’s sliced eye in Un Chien andalou to to the blind man pushed aside in L’age d’or (fig. 1), vision is constantly present as one of the predominant tropes in Surrealist film. Vision is, of course, a predominant theme in Surrealist works across many media, however in film, a medium which inherently takes vision as its subject, the Surrealists found particular success in its exploration. In her article on Dalí’s attraction to the cinema, “Why Film?,” Dawn Ades elaborates on this relationship, and on the Surrealist possiblities allowed for by the techincal medium of film. The key to the relationship, claims Ades, lies in film’s “imaginative possiblities, which are still rooted in fact,”[1] that is to say, the power of film to simultaneously relate to and differ from vision:

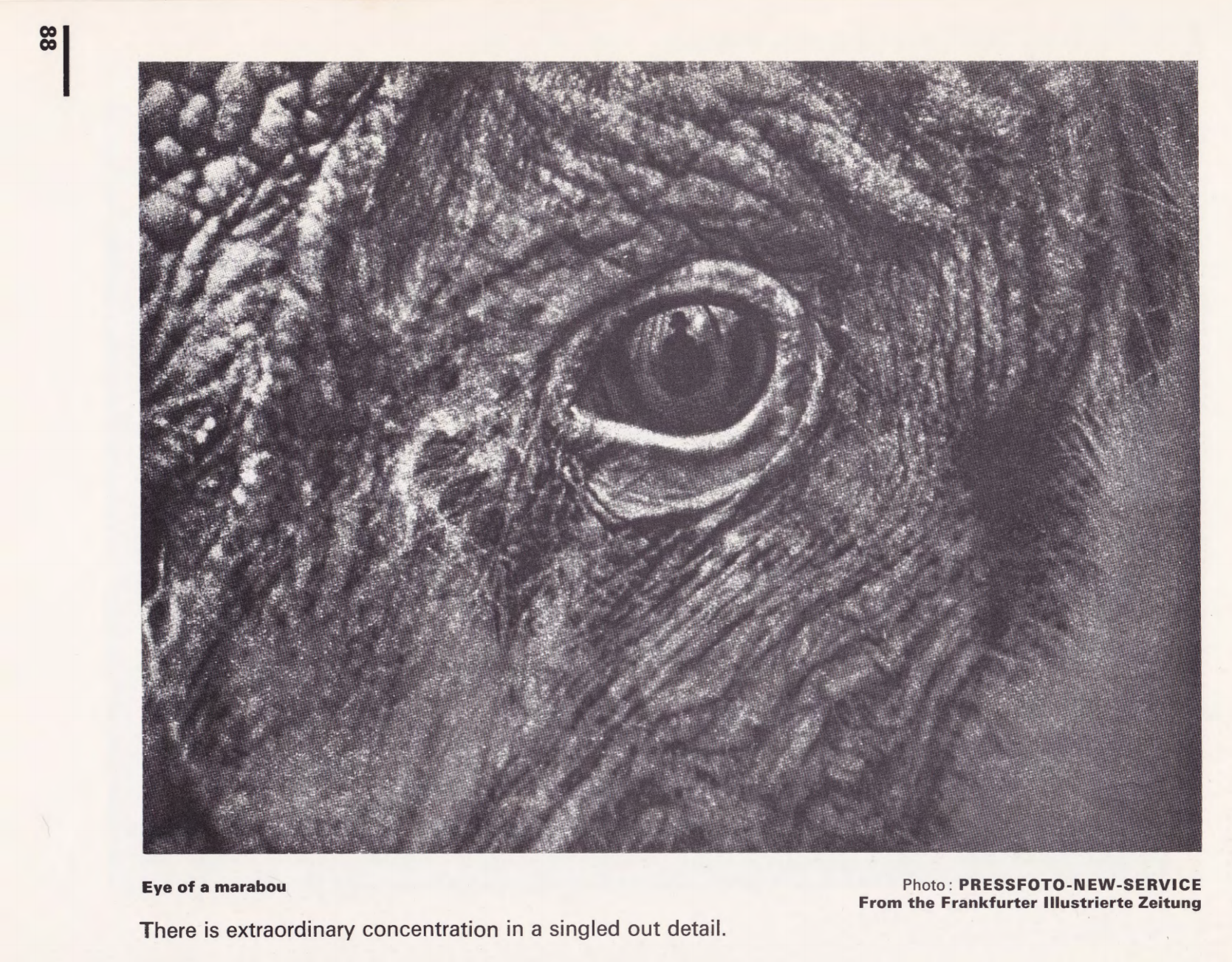

This ‘photographic imagination’ owes much to technical possiblities, such as the close-up and slow motion. The poetic magic of the ‘film-fact; comes from its ability to transform the reality we see before our eyes. Seizing on László Moholy-Nagy’s notion, in his influential Bauhaus book Malerei Fotografie Film (Painting Photography Film) 1925, that the camera is an extension of ‘our optical instrument, the eye,’ Dalí emphasised its tranfsformative powers: ‘A lump of sugar on the screen can become larger than an infinite persepctive of gigantic buildings.’ One of the photgoraphs in the last issue of L’amic de les Arts was filched b Dalí from Painting Photography Film, a close-up of the eye of a marabou (mistitled by Dalí ‘Ull de’elefant’—elephants eye.) The inventive visuality of the close-up was explored in Un Chien andalou, for instance in the sequence magnifying the death’s head hawk moth.[2]

Here Ades pinpoints the most singular aspect of vision in Surrealist film. Surrealist film is not meant to merely represent vision, whether through allegory (like the blind man or the cutting of the eye) or more literally (as in the use of shot countershot, for example), but to change vision.

Figure 2 — A blurry couple approaches in Man Ray’s L’étoile de mer.

Thus Dalí leans on the credibility of Moholy-Nagy as a scholar of new vision, taking up Moholy-Nagy’s association of the camera with the eye, a metaphor which bears weighty consequences for perceived “truth” of the image. If the camera is the eye, then what we see on screen is what we see in reality; we can trust film and photography to reproduce our perception with accuracy. Dalí leverages this trust in the image towards Surrealist ends. Through the use of these “technical possibilities”—macro lenses and extreme close-ups, slow motion, footage played in reverse, the hand-held camera, etc.—Surrealist film can present unfamiliar images, which stretch the limits of vision and imagination, with a certain level of veracity. As such, the milky blur of many a shot throughout L’étoile de mer (fig. 2), for example, apparently achieved by placing an imperfect glass filter in front of the lens, are read not as abberations of the film, but as abberations of our own vision. Thus, the “film-fact,” the apparent truth of what is presented on screen, becomes “poetic magic,” by means of the “transformative powers” of the camera, which correspond to various mechanical techniques of film making. Cinema becomes a ‘priveleged instrumted for the derealizing of the world,’ a ‘transmutation of reality,’ as Bretón says.[3] A lump of sugar, by means of the extreme close-up, is rendered literally larger than a cityscape, before our eyes.

Figure 3 — Eye of a marabou from Moholy-Nagy’s Painting Photography Film

A similar transformation is illustrated by Dali’s photograph, via Moholy-Nagy, of the marabou’s eye (fig. 3). The wrinkled skin, robbed of its surrounding context by means of the close-up, now resembles a scorched landscape seen from above[4]—wrinkles become mountain ridges, splotches become vegetation, the eye at the center of the photography becomes a still lake. In the lake is reflected the silhouette of the photographer himself, a man in a hat, creating an unspoken shot-countershot relationship. The camera is the eye, our eye, and thus the man reflected in the eye is our self.

Figure 4 — Extreme close-up of a butterfly from Un Chien andalou

This “inventive visuality” is demonstrated yet again in Un Chien andalou, in the shot mentioned by Ades, this time to even greater transformative effect. A butterfly rests on the wall; in two successive cuts, one with a circular vignette, the camera moves to an extreme close-up of the butterfly’s back (fig. 4), the pattern resembles a human face, another cut and a man appears in place of the butterfly. Here the transformative power of film goes beyond the “photographic imagination,” and the transformation which might otherwise take place in the mind of the viewer, is realized on screen. The film often progresses by the use of such associations, such that it is no longer merely the viewer’s perception (their relation to the external world, the eye) which is projected on to and associated with the frame, as in Moholy-Nagy’s photograph, but the viewer’s thoughts (their relation to the internal world, the mind’s eye) which are projected on screen. Thus, in film, “Breton called for the abolition of artificial boundaries between what we see and what we only ‘begin to see’, or have never seen before,” or as Fotiade puts it, “[s]urrealism senses the miraculous potential of the cinema in this direction of the unseen, the unknown.”[5] The intense obsession of Surrealist film with vision results, in fact, in an quintessential Surrealist contradiction: the point of contact between vision and that which cannot be seen, the unseen.

[1] Dawn Ades, “Why Film?” in Dalí and Film, ed., Matthew Gale (New York: MOMA, 2008), 17.

[2] Ibid.,19.

[3] Bretón quoted in Ramona Fotiade, “The slit eye, the scorpion and the sign of the cross: surrealist film theory and practice revisited,” Screen 39, no. 2 (1998): 114.

[4] Aerial photography itself was still a relatively new form of vision, pioneered by Nadar at the end of the 19th century, and one which Moholy-Nagy himself explored, as in his photograph from the top of the “Berlin Radio Tower”.

[5] Fotiade, “The slit eye, the scorpion and the sign of the cross,” 114.

Surrealist Film Themes: Religion

The presence of the Church and the function of religion in Western society were powerful and prominent themes in many Surrealist films. Given that surrealism first had its start in the early 1920s after the First World War, major Surrealist thinkers at the time including André Breton were at the forefront of critiques and discussions about theories of governance and social organization as well as about the efficacy of the powerful, ruling institutions which were rooted in capitalistic theories of efficiency and structure. Breton and many of his peers, in fact, were affiliated with Communism at the beginning of the Surrealist movement, and Breton even mentioned the “specter of Communism” over Europe in his First Surrealist Manifesto. Thus, Breton and other surrealist thinkers were deeply concerned with the methods of social and political organization that have an effect on the everyday lives of the individual.

The political, social, and religious are and were all erroneously intertwined and prescribed by these ‘contemporary regimes’ that profited off stifling the imagination and desires of the individual argues Clifford Bower in one of his two extensive biographies of Andre Breton entitled André Breton, Arbiter of Surrealism.[1] Bower maintains that Breton was particularly interested in the formation of and replacement of popular myths. It is no wonder then that Breton argued that modern art and poetry that could replace the myth perpetuated these regimes. In fact, modern art and poetry could create a ‘myth nouveau’ that would protect people from these contemporary systems of thought and place satisfaction of human desires as a main priority whilst ignoring and destroying the political, scientific, and religious institutions currently in place.

Film is, arguably, one of the most powerful forms of modern art, because it combines both visual and narrative, whether or not that narrative makes perfect sense is another story, so as to emphasize some of the themes of the Surrealist movement. As Breton argued, visual and artistic mediums were also at the forefront and early stages of creating this new myth that could replace the myths promoted by political regimes. As Clifford Bower states, modern art and poetry were creating “embryonic forms” of a “mythe nouveau” that would be essential for creating a “future civilization” that could “supplant moribund Christianity, demolish scientific positivism and satisfy the deep human desires repressed or ignored by all contemporary regimes.”[2] As such, art and poetry were essential for promoting Surrealist ideals and overriding the myths currently perpetuated by the powers that be, particularly capitalism, corrupt government systems, and the Catholic Church. In many ways, the few surrealist films made seem to be a combination of art and poetry that often deliberately and quite explicitly point out flaws in the current ruling institutions including that of religion.

Allusions to religion as a social and political institution are made quite obvious in many surrealist films including the films that we have looked at more in-depth throughout this blog. Most of the films feature the complicated relationship between the authority of the Church and religion and the presence of the thoroughly commonplace and yet lionized human sexual desire. The reference to religion and authority is made clear in the title of Germain Dulac’s film The Seashell and the Clergyman wherein a priest struggles with his intimate desires for the wife of a military general. Luis Buñuel’s Un Chien Andalou features a young man thoroughly overcome by sexual desires doing things like wearing a nun’s habit, carrying the Ten Commandments on stone tablets, and pulling two priests through a bedroom, all in the perverse pursuit of satisfying his sexual desires with the main female protagonist.

Buñuel’s L’ Age D’Or features some of the most overt references to the hypocrisy and failings of the Church especially as it relates to the creation and maintenance of a rich and desirous elite class of people with little concern for the lives of those in the working class. As scholar of surrealism, Allen S. Weiss, argues, the setting of the film is, in itself, quite ironic and expository. The film is set in Rome and St.Peters, the site of the Vatican and a center of Christianity. Yet the film ends at the Chateau de Selliny where a violent orgy took place. The last scene in the film showcases a cross adorned with the scalps of those who participated in the orgy.[3] Weiss concludes that “surrealism attempted to constitute one such set of sovereign, revolutionary laws, and utilized a perverse iconography to express its rebellious critique of culture. L’Age d’or is a love story which is organized according to such a transgressive mode of eroticism.”[4] Thus, L’Age D’Or like Un Chien Andalou, is an atypical romance meant to confuse but also to elucidate the connection between sex, violence, and religion by way re-appropriating symbols like the cross in L’ Age D’Or or the nun’s habit in Un Chien Andalou. Surrealism was meant to be a “rebellious critique of culture” as both Allen Weiss and Clifford Bower explain, and surrealist film succeeded in doing this often by placing the political, cultural, and social institution that is the Church at the forefront of this argument.

[1] Clifford Browder, André Breton, Arbiter of Surrealism (Genèva: Droz, 1967), 147.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Allen S. Weiss, “Between the Sign of the Scorpion and the Sign of the Cross: L’Age d’Or,” in Rudolf E. Kuenzli, ed., Dada and Surrealist Film (New York: Willis, Locker & Owens, 1987), 159.

[4] Ibid., 161.

Surrealist Film Themes: Violence and Desire

Surrealists sought for a more expressive means of existence; one that resided in the unconscious mind and needed to be liberated from the tyrannical oppression of the conscious mind. The surrealists “sought a revolution against the constraints of the rational mind; and by extension, the rules of a society they saw as oppressive” (“MoMA Learning”). They recognized the traits valued by society: logic, reason and productivity, and devised a way to challenge this. Contrary to the Dada movement, which focused on protest but did not necessarily propose alternatives, the surrealist offered a way of life. They explored topics such as desire, religion and violence, “breaking taboos and shocking viewers in their depiction of mutilated, dismembered, or distorted bodies” (“MoMA Learning”). They challenged the rules of society by not depicting topics that had been tacitly proscribed. While they were widely perceived as avant garde, their response was appropriate for the time and “such visions may have had particular resonance given the still-pervasive sight of World War I veterans—many left limbless or using prosthetics” (“MoMA Learning”). They choose to address all the ideas and discontents that had been silenced, particularly in regards to the government’s dictation of how people should live and its manipulation of and disregard for what is in the best interest of its citizens.

In the Dada Manifesto of 1918, Tristan Tzara writes, “I speak only of myself since I do not wish to convince, I have no right to drag others into my river, I oblige no one to follow me and everybody practices his art in his own way” (Lippard 15). Tzara expresses desires to neither restrict not define art. As a Dadaist, he uses it as a form of protest, a practice the surrealist movement continues. While the surrealist are concerned with the way art is experienced and used as a means of protest, they are very concerned with the way people experience the world, and they would like to revolutionize everyday life. Their disappointment with the thousands of people being wounded, maimed and killed in war pushes one group to revolt, and the latter to propose an alternative, a way of living focused on the individual and their personal fulfillment.

The surrealists dedicate their time to themes such as violence, religion and desire. They were fond of Sigmund Freud, notable psychoanalyst, who published his discussion about the basic instincts and the stigma associated with them in his entitled work, Civilization and Its Discontents. He writes, “It is impossible to overlook the extent to which civilization is built up upon a renunciation of instinct,” identifying the very problem surrealist are determined to address: neglect of the imagination and suppression of the unconscious mind (Freud 84). Surrealists continue this discourse about instinct, and engage the concepts of Eros and Thanatos, ideas that Freud had previously broached in Beyond the Pleasure Principal in 1920. Eros refers to the desire of self-preservation and pleasure. It encompasses the instinct to reproduce and the pleasure associated with sex, self-nourishment and the instinct to avoid pain. Thanatos is the death instinct, the violent part of each being. Surrealist work is constantly juxtaposing the two. Erotic images and powerful, sensual colors are often coupled with death and violence (Freud 334 Beyond the Pleasure Principle). They capture the natural preoccupation with the body, its fulfillment but also its pending demise. They readmit the importance of urgency into the lives of those who would like to join the movement, they believed that the “creativity that came from deep within a person’s subconscious could be more powerful and authentic than any product of conscious thought” but this requires embracing what is natural to oneself and not what society has demanded (“MoMA Learning”).

An Andalusian Dog illustrates the interest in eroticism and violence (discussion to follow). A man cuts a woman’s eye; perhaps a representation of the way the unconscious mind, associated with femininity, is inhibited by a male dominated society. Someone plays with a severed hand; the concept of being maimed recurs in Surrealist work, a reflection of the discontent with WWI. There is the juxtaposition of concepts that society has deemed worthless and unnecessary. It has convinced people to renounce their desires and pursue what is best for the common good, inhibiting the imagination in the process. Surrealist are not arguing for a world filled with debauchee, they are arguing against the way society has manipulated its citizens for its own purposes and failed to allow the individual personal fulfillment and access to the unconscious. By depicting the very instincts society has oppressed or perverted for its own benefit, they force the viewers to confront the nature of the lives that have been imposed upon them and encourage them to embrace a new way, the way that can be illuminated through the unconscious mind.

Diderot, Denis, and Jules Assézat. Oeuvres completes de Diderot. Paris: Librairie Garnier Frères. 1751. Print.

Freud, Sigmund, and Peter Gay. The Freud Reader. New York: W.W. Norton, 1989. Print.

Freud, Sigmund, and James Strachey. Beyond the Pleasure Principle. New York: W.W. Norton, 1975. Print.

Freud, Sigmund, and James Strachey. Civilization and Its Discontents. New York: W.W. Norton, 1962. Print.

Lippard, Lucy. Dadas on Art: Tzara, Arp, Duchamp and Others. New York: Dover Publications. 1971. Print.

“MoMA Learning, Surrealism.” MoMA Web. 12 May 2015

Surrealist Film Themes: Language and Dreams

There exists a close relationship between Surrealist film, dreams and language. In film, the “surrealists hope[d] that the new medium would overcome both the static nature of painting and the shortcomings of spoken or written language—becoming the medium of academic art.”[1] The possibility of a visual language was one that was especially exciting to the Surrealists, who saw from the very beginning that automatic writing was “especially conducive to the production of the most beautiful images”.[2] Could film, then, provide a means of bringing those images to life? Indeed, “[i]nteresting connections can be made between the discovery of the cinematographic image, of editing, and the ‘automatic writing’ proposed by Breton and his friends as a deconstructivist technique, uncovering the unconscious processes of desire in their fragmentary, illogical form.”[3] Film, the Surrealists soon discovered, exhibited many of the qualities of language: syntax, metaphor, metonymy, synecdoche, etc. In film the peculiar transformations, associations and combinations allowed by syntax and grammar are found once again, though in a visual means.

This is especially true of montage, a technique which was itself developing concurrently with Surrealism; Sergei Eisenstein, pioneer of filmic language and an avid supporter of montage, released his seminal film Battleship Potemkin (1925) just one year after the first Manifesto of Surrealism (1924). Montage was particularly well suited to the Surrealist penchant for disjunctive images and seemingly unconscious associations, both visual and textual. Indeed the Surrealists often combined, as in the “Si belle! Cybèle?” from L’etoile de mer (see the previous page). Despite these inherent connections however, the translation of automatic writing from page to the silver screen remained a question, one which was perhaps never answered successfully: “It is doubtful that surrealism ever succeeded in validating its practice of automatic writing in film, although the suggestion for such spontaneous expression of one’s deepest feelings and desires might have come from the cinema, as well as from Freudian investigations of the unconscious.”[4] While the connections between filmic language and the language of automatic writing were strong, film did not enjoy the same direct connection between creation and consumption. One might right an automatic text and call it a screenplay, but to translate it into images on film required a long series of conscious decisions—staging, lighting, props, filming, editing, etc.—and that assumes that the whimsical, unconscious screenplay was physically possible to stage in the first place (and for this reason, many Surrealist screenplays remained un-filmed).

A possible solution, however, lay at the intersection of these three vectors, the unconscious, language and image—in dreams. In fact, dreams, it seemed to the Surrealists were already cinematic in themselves, exhibiting “all the expressive and visual processes of the cinema are found… the simultaneity of actions, soft-focus images, dissolves, super-impositions, distortion, the doubling of images, slow motion.”[5] Wendy Everett continues:

The parallels between film and dream are too numerous to be explored in detail here, and are in any case widely recognized: both normally occur in the darkness; both create alternative universes which absorb and enthrall; both proceed via moving images which are simultaneously real and unreal, illogical and disturbing; both express the hidden realms of desire and the subconscious and so on. However what really interested the surrealists was not a facile imitation of dream content, nor yet the attempt to make films that pretend to be dreams… but the exploration, through film, of the mechanics of the dream… ways in which dream and film function as systems of communication which differ significantly from verbal language.[6]

As Everett explains, it is not only that film displayed “perceived similarities to the state of dreaming,”[7] but that this relationship could work in reverse; that not only could film imitate dreams, but that dreams could provide for film, through their shared system of visual language (rather than the verbal), a script for a film. In the dream, as in film, our mind combines images with the ease with which we combine words in sentences. In this way, the dream might be seen as the automatic writing of a film script. Such is supposedly the case for Un Chien andalou, which is the result of several dreams had between the filmmakers, Dalí and Buñuel. Of course, however, the mediation in between the dream and the creation of the film was still a present problem, and perhaps this accounts for the extreme scarcity of Surrealist films produced.

hi