Section IV: Surrealist Objects and Perception

Objects were an important part of the Surrealist agenda to revolutionize the world, so naturally the Surrealists were concerned with how their objects would be interpreted. The ways in which Surrealist objects were perceived (or meant to be perceived) by the senses was critical to their subversive function, especially in comparison to offshoots of the movement elsewhere in the world. In particular, it is worth looking more closely at filmmakers of the Czechoslovak New Wave movement because of the new perspective on Surrealist objects proposed by their films, especially in the way that objects derive meaning by context. This section will trace distinctions between the Czech and French Surrealist groups, the role that cultural milieu played in each group’s approach to objects, and provide a new way of understanding Surrealist objects and their contexts through the work of the Czech Surrealists and their artistic descendants. Largely devoid of the fantastic element so often associated with Surrealist works, Czech New Wave cinema of the 1960s in fact uses a documentary-influenced style to reveal the Surrealist nature of objects through their everyday contexts, unlike French Surrealist objects which typically were displayed in more rarefied and eccentric contexts.

Whether an object is perceived as Surreal or not has everything to do with context–Surrealism itself was defined by Breton in the First Manifesto as the juxtaposition of “two distant realities” to form a new one. Sensory perception, of course, is inherently diffuse and subjective, and the Surrealists recognized this ambiguity to be correspondent with the multiplicity of meanings in everyday objects. This lent Surrealist objects a certain political or revolutionary capacity: because objects could be perceived in many different ways, the Surrealists could use them to subvert traditional signification. In addition, the senses often define “reality” as such, and in turn the Surrealists created highly specific environments to shape the perception of their objects, such as the exhibitions discussed in a later section of this blog.

Early Surrealist works demonstrate a preoccupation with visual perception and the eye, suggesting an endorsement of vision as the foremost arbiter of sensory information. In the First Surrealist Manifesto (1924), Breton famously recalls seeing “the faint visual image” of a man cut in two by the window. Indeed, much of the material we associate with the Surrealist movement (and Surrealist objects in particular) is intimately tied to the way we see them. Yet these works did not necessarily reflect an attraction to or admiration of vision; Buñuel’s Un Chien Andalou (1929) features the famous (or infamous) scene of an eye sliced in half by a razor blade, suggesting a degree of mistrust in the literal sense of vision. As Johanna Malt notes in Obscure Objects of Desire, Breton was first and foremost a poet, and saw poetry as the ultimate surrealist medium. Though he grew increasingly interested in vision and objects from the late 1920s onward, Breton saw language as “the prime mediating force between the subject and the world” (Malt 146) As Malt points out, the images Breton is so preoccupied with are in fact images of the mind’s eye, created in response to language, rather than perceptual or imaginary images recorded in visual form.

Luis Buñuel, Un Chien Andalou (1929)

Luis Buñuel, Un Chien Andalou (1929)

Perhaps, then, a more useful term for the primary Surrealist sensation (at least according to Breton) is a sort of “imaginative vision”–perceiving images in the mind as sparked by language, not necessarily as perceived by the eyes. Certainly, the Surrealists were very concerned with interiority and personal experience, and as such their objects were meant to affect the human subject through an imaginative sensation. The Surrealists were often attacked for what many of their contemporaries considered to be an overemphasis on the imagination and interior (un)consciousness. Some critics see Breton’s recourse to the object and his attempts to objective language as a response to his own intuition of the problems of subjectivity that his work presents (Malt 151). The Surrealist movement in Czechoslovakia is an interesting phenomenon to study in this regard both because of that group’s close ties to French Surrealism and in light of their unique cultural milieu (Czech Surrealist work was often influenced by closer ties to the Communist Party and its origins in Marxist materialism). Modifying the Paris group’s approach to reality (if ever so slightly), the Czech Surrealists’ position was perhaps best encapsulated by Vratislav Effenberger, one of the leaders of the group after World War II: “Imagination does not mean turning away from reality but its antithesis: reaching through to the dynamic core of reality” (Hames 34). For the Prague group (and especially the artists and movements they influenced), this “reaching” would address objects differently in regard to their contexts through both literal and imaginative vision. Comparing French Surrealist objects to Surrealist objects in Czech New Wave film perhaps provides a clearer or more developed model of how we perceive objects to be Surreal.

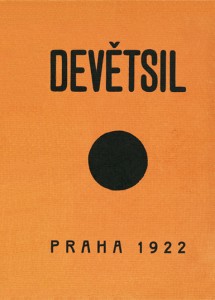

While French Surrealism grew out of the Dada movement, Czech Surrealism found its origins in Poetism, which was part of a larger avant-garde movement in Czechoslovakia known as Devětsil. Devětsil, like Dada, reacted to the barbarity of WWI and rejected modern technology, but was less nihilistic than its French counterpart, embracing leftist politics, folk art, traditiona l lifestyles and “simple pleasures” (Frank 40). Devětsil would turn toward a more Constructivist position by 1922, privileging technology instead of rejecting it, and Poetism emerged within Devětsil in 1924 as a more playful and imaginative offshoot, even hedonistic. Devětsil and Surrealism evolved toward each other in the late 1920s: the Czechs grew more interested in the unconscious (as evidenced in Karel Teige’s Second Manifesto of Poetism, 1927-28), and Breton’s Second Surrealist Manifesto (1929) “reflected a commitment to dialectical materialism” (Frank 41). Viětslav Nezval, one of the foremost writers and thinkers of Devětsil, met Breton in Paris and founded the Czech Group of Surrealists in 1934. In 1935 the Czech group presented the first Czechoslovak Surrealist Exhibition; later that year, Breton and Eluard visited Prague for two weeks, and Breton gave three lectures (including one on “The Surrealist Position of the Object”). Breton and his companions were generally well-received in Prague, but most Czech activist-artists (particularly those outside the Czech Surrealist group) were more strongly affiliated with Communism, more concerned with socialist realism, and less interested in the unconscious (Huebner 248). Reflecting their social milieu, Czech Surrealist objects became much more political and pessimistic after World War II.

l lifestyles and “simple pleasures” (Frank 40). Devětsil would turn toward a more Constructivist position by 1922, privileging technology instead of rejecting it, and Poetism emerged within Devětsil in 1924 as a more playful and imaginative offshoot, even hedonistic. Devětsil and Surrealism evolved toward each other in the late 1920s: the Czechs grew more interested in the unconscious (as evidenced in Karel Teige’s Second Manifesto of Poetism, 1927-28), and Breton’s Second Surrealist Manifesto (1929) “reflected a commitment to dialectical materialism” (Frank 41). Viětslav Nezval, one of the foremost writers and thinkers of Devětsil, met Breton in Paris and founded the Czech Group of Surrealists in 1934. In 1935 the Czech group presented the first Czechoslovak Surrealist Exhibition; later that year, Breton and Eluard visited Prague for two weeks, and Breton gave three lectures (including one on “The Surrealist Position of the Object”). Breton and his companions were generally well-received in Prague, but most Czech activist-artists (particularly those outside the Czech Surrealist group) were more strongly affiliated with Communism, more concerned with socialist realism, and less interested in the unconscious (Huebner 248). Reflecting their social milieu, Czech Surrealist objects became much more political and pessimistic after World War II.

The role of objects in Czech New Wave cinema in particular allows a useful framing of the Surrealist object in terms of its various contexts, both interior and exterior. Though not formally influenced by either the French or Czech Surrealists, the New Wave built on these groups’ use of objects, pushing the Surrealist function of objects to a different and perhaps broader social realm. The Czech New Wave was a cinematic movement that emerged in the 1960s. Like Czech Surrealism, the movement evolved out of Devětsil, though the New Wave was primarily inspired by pre-World War II Surrealism and Poetism, and less so by the Czech Surrealist Group which was still active in the 1960s (Frank 41). Though the two movements overlapped in their profound concern for physical reality, New Wave films were starkly realist and often took a documentary approach. Czech New Wave filmmakers (especially the documentary-influenced branch of the movement) also took a comic approach to everyday objects, portraying them as having multiple meanings. Though these directors were interested in social realism (and many of these films are categorized as such), some critics have suggested that this approach was inherently Surreal (Frank 43). Of course, the Czech New Wave emerged decades later than the primary thrust of Surrealism, and indeed the medium of film itself was critical in allowing this kind of everyday appeal. Yet this is not to say that this kind of portrayal would not have been possible without film. This analysis compares Czech-filmed objects to physically-displayed objects in Paris in order to propose the potential for a broader and more profound exploration of Surrealist objects via their contexts in Czech New Wave film. As “real” as Surrealist objects were—that is to say, as physically and materially accessible to the viewer—they were nonetheless presented as art objects on display. With a few notable exceptions, perception of these objects was largely restricted to the sense of vision, not unlike their counterparts in Czech New Wave film.

Věra Chytilová, Daisies (1966)

By expanding on the prior critical analysis of certain New Wave films, a useful framework emerges for categorizing the perception of Surrealist objects. These categories encompass and expand on Surrealism’s imaginative interiority through three types of context: objective, subjective, and symbolic. In an article in the film journal Kinema, Alison Frank discusses three New Wave directors in particular (Miloš Forman, Ivan Passer, and Jan Němec, together known as ”The Forman School”) and the way their films portray everyday items in a number of different contexts, making them Surreal. Objects are made Surreal by three types of context in these films: objective or physical context, subjective or experiential context, and functional or symbolic context. Notably, these contexts are defined in relation to the lives and perspectives of the films’ characters; unlike objects on display in French Surrealist exhibits, which are directly presented to the viewer, these films obscure the Surrealist function of their objects by interactions between ordinary individuals, requiring a secondary order of interpretation and firmly planting objects within a constructed social reality.

Passer’s Intimate Lighting (1965) follows Peter, an urbanite symphony musician who visits his old friend Bambas in provincial Czechoslovakia. When a flock of chickens finds its way into Bambas’ garage, Passer presents a Surrealist image that characterizes the first type of context: objective or physical. This image is Surreal precisely because the live, frantic, dirty chickens are physically juxtaposed with the still, silent vehicle that Bambas works so hard to keep presentable. Later, Bambas angrily chases the chickens out of the garage, “while his mother-in-law protests that he is scaring them and that ‘they’ll stop laying eggs’” (Frank 48). Here Bambas’ perception of the chickens as a nuisance stands in contrast to his mother-in-law’s concern for the chickens as living creatures, and this confrontation is inherently Surreal as well, demonstrating the second type of context (subjective or experiential). Finally, Bambas’ bitter observation that the chickens have made his garage “‘more like a hen house’” highlights the functional type of context (Frank 47). The garage, intended as a space for storing the car, is contrasted with an incongruous function—that is, of facilitating the hatching of chickens’ eggs. This suspension of function is too a Surreal one, and contexts such as these lend the film much of its humor.

Ivan Passer, Intimate Lighting (1965)

Ultimately, while French Surrealists and Czech New Wave filmmakers shared a concern for the perception of objects, the latter group expanded the notion of what could make an object Surreal by aesthetically exploring social contexts for these objects in documentary-style film. These films allow a more profound understanding of the kind of contexts which lead us to perceive everyday objects as Surrealist ones.