Section VI: Collective Objects and Exhibitions

After developing an understanding of the theoretical and empirical qualities of surrealist objects, we have examined how these objects are dematerialized and how they are perceived by the senses. To contextualize this study, we have examined a different national type of surrealism and the political import of surrealist objects. We conclude our analysis by discussing the physical context of surrealist objects as they are manifested in collections and exhibitions.

Though surrealist objects surfaced in the twentieth century, their mode of display gets its inspiration from the origins of museums—the cabinet of curiosities. The cabinet of curiosities, also known as the cabinet of wonders, emerged predominantly during the European Renaissance and consisted of eclectic collections of objects with undefined categorical boundaries. These objects may originate in nature, geology, archaeology, ethnography, religion, or art. Seen as extraordinary in some way, they frequently attempted to convey certain themes or narratives. In surrealism, Breton’s objects and compilations often exhibit characteristics of these early “museums.” According to Malt, “Breton’s poème-objets often allude to the traditions of the cabinet of curiosities, drawing on a history of attempts to encompass and order knowledge in the miniaturized universe of a single case.” (Malt 167). In his version of a cabinet of curiosities—his wall—Breton desired to question the conventions of object display and manipulate ordering principles.

Breton’s wall in his studio at 42 rue Fontaine is a clear example of this aim. Constructed over a few decades of wandering auctions, flea markets, ateliers, and the world at large, Olalquiaga calls his a “cabinet of wanders” rather than a “cabinet of wonders.” (Olalquiaga). The wall consists of found objects, interpreted objects, mathematic objects, natural objects, ready-made objects, mobile objects, and works of art, which are displayed on his desk and wall within various cases and rows of shelves. With his compilation, Breton rejects rules of rational classification and instead draws on a more irrational, poetic aesthetic. Operating under the concept of the “will to objectify” (Olalquiaga), Breton strives to divorce objects from intellectual abstraction and practical usage and instead emphasize the unique experience they provide. His objects and collections are important in the experience they facilitate, rather than in and of themselves.

To shape and transform its experience, Breton carefully assembled the wall behind his desk. A photographic portrait of Breton and his wall referenced by Malt suggests a close identification between Breton and his wall. The myriad of objects from a wide time frame show various aspects of Breton’s interests and mentality. The wall’s variety and shift over time relates to Breton’s own restless spirit and his support of the notion of changing in order to remain true to oneself. According to Olaquiaga, this change may entail political alliance, love partners, or objects themselves. It also represented his “subversive desire that chose representation as its privileged territory of combat.” (Olaquiaga). In essence, she contends that the wall contained his heart and mind in fragments. A tension may exist in this interpretation in that observers view the wall with the set purpose of gaining insight into Breton’s identity rather than simply allowing themselves to experience the sentiments provoked by the collection without ulterior motives. However, it seems likely that in assembling the wall Breton focused on the experience it would provide rather than its biographical role.

The wall itself exhibited an extremely varied collection of objects and mediums. Among the three largest paintings hanging directly on the wall is Le Double Monde: L.H.O.O.Q (1919) by Francis Picabia, containing a reference to Duchamp’s assisted ready-made L.H.O.O.Q. The center painting is Peinture (Tête) (1927) by Joan Miró, while the third and rightmost tableau is Jean Degottex’s Pollen Noir (1955). These three rather abstract paintings are from different decades and do not display a coherent theme or recognizable pattern. Because they do not seem to intentionally convey a specific, intellectualized meaning, then, it seems that these objects exist rather as a means for creating an experience. In addition, by providing such abstract representations, these paintings sharply contrast with the material objects on the desk below. With this tension, Breton adds complexity to the experience offered by his compilation.

Other objects displayed on the wall consist of paintings, photography, and tribal, sculpted pieces.

An Untitled 1943 work by Roberta Echauren Matta.

Vassily Kandinsky’s Petit Blanc.

Untitled work by Roberto Echauren Matta resembling a white, vaginal-like opening.

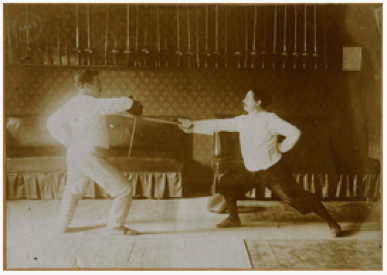

Photograph by an unknown photographer showing Jarry the fencer with Master of Arms Blavie.

Tribal objects from far ranging places from New Mexico and New Guinea to Australia and New Zealand ornament the walls, including a gold and green disk called Tambour hopi; a carved Asmat shield by Irian Jaya; an Aborigine painting on bark; and a sculpture of a bivalve shell entitled Tiki maori.

Various other assorted objects also exist on the walls, such as Joan Miró’s wood, chain, and metal work entitled Homme et Femme.

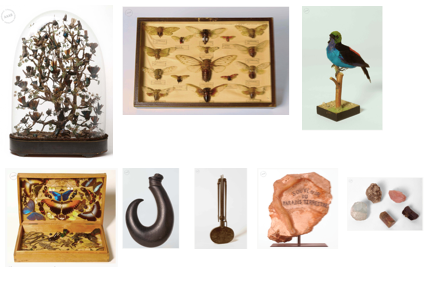

On the surface of Breton’s desk one finds shelves containing a wide variety of seemingly disparate objects. Many of these objects are or are reminiscent of natural creatures. Among this sort we find a globe containing exotic birds, a box of sixteen species of cicada, a blue bird in a glass box, and another box containing butterflies and other creatures. Some objects allude to the use of these animals for human consumption, such as a hook for bait and a mussel opener. Other natural inanimate objects include a wooden fossil, a stone found by Breton and interpreted as a “Souvenir of Earthly Paradise,” and a collection of four stones and one tourmaline.

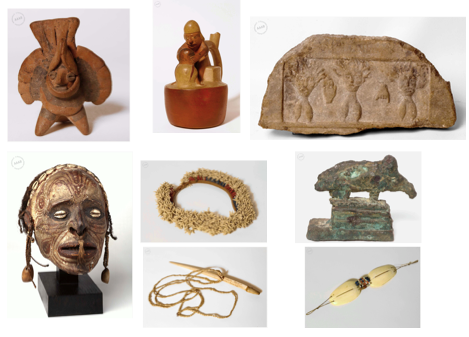

An assortment of human-like statuettes exists as well. In the tribal vein, a series of anthropomorphic, terracotta statuettes from the Mexican valley sit on the shelves, along with a variety of other Mexican feminine statues. Three rock-sculpted, medusa-like women with hanging breasts are separated by 2 inverted hands in Ex-voto. Further, the desk displays an ornamented New Guinean modeled head. Other non-anthropomorphic tribal objects include a crown of pearls, dolphin teeth, and other fibers from the Marquis islands, an arrowhead necklace made out of bone, a bronze boar Egyptian sculpture, and Eskimo glasses. The various head statues are dispersed throughout the shelving atop Breton’s desk, while the statuettes are mostly clustered around the viewer’s eye level. Their clustering evokes reflections on humanity and its more “wild” characteristics but deters the observer from focusing on one specific piece, instead encouraging them to more holistically experience the collection.

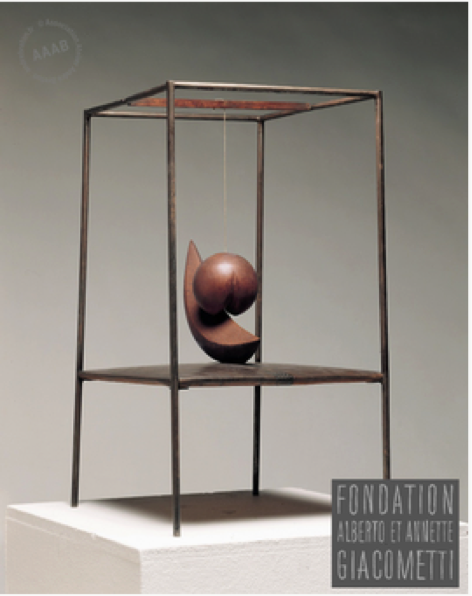

Fewer nontribal objects seem to exist. Among these we find what seems to be Breton’s centerpiece: Alberto Giacometti’s wooden Suspended Ball sculpture. This object occupies such a place of honor because it was said to encapsulate the essence of surrealism. As referenced in the Second Manifesto, Breton closely equated alchemy and surrealism, as both were about relationships between two components. He interpreted this object as an alchemic sun and moon, symbolizing the male and female sexual parts. A sorcerer’s mirror with small, reflective surfaces within the main surface of the mirror is another inanimate, nontribal object of interest which suggests Breton’s burgeoning fascination with the occult.

The proliferation of tribal objects in Breton’s collection is indicative of his wanderings and also perhaps of his ideology. The tribal objects, alongside the animal-related objects, stimulate a certain kind of experience that evokes the subconscious or basic desires connecting human and animal. The largely sexual nature of these desires is consistently evident among the objects found on Breton’s wall—with phallic elements and various orifices in the objects all tied together by the central Suspended Ball piece—thereby connecting his collection with some of the principle tenets of surrealism.

Turning to focus on exhibitions of surrealist objects, we will first note that this personal exhibition of Breton has been exhibited at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. The Centre Pompidou organized a broader exhibition of surrealist objects, entitled “Surrealism and the Object,” from October 30, 2013 to March 3, 2014. The exhibit encompassed numerous other surrealist exhibitions, dating back to 1933, and contained excerpted versions of each exhibit in different rooms. In this way, this Pompidou exhibit treats each of the earlier exhibits as large, collective objects in and of themselves. The following video clip gives a brief overview of the exhibit and surrealism as a movement.

This modern exhibit includes three major pre-war surrealist exhibits: that of 1933, 1936, and 1938. The International Exhibition of Surrealism at the Pierre Colle Gallery in 1933 is aptly characterized by Tristan Tzara in the preface of the accompanying catalogue: “Unpleasant objects, chairs, drawings, sexes, paintings, manuscripts, objects to sniff, automatic and unmentionable objects, wood, plasters, phobias, memories from the womb, elements of prophetic dreams, dematerializations of desires…do you still remember the time when painting was considered “an end in itself”? We have moved on from the period of individual exercises…time passes. Through the emotional characters of your meetings. Through the experimental explorations of Surrealism…” (“Surrealism and The Object.”) The Centre Pompidou’s informational guide describes the Surrealist Exhibition of Objects at the Charles Ratton Gallery as quintessentially surrealist and focusing on the ability to transfigure and transmute objects, and thereby reality itself. Finally, the International Exhibition of Surrealism of 1938—quite extraordinary for its time—included an entrance hall of mannequins taken from department store windows and lining either side of the surrealist street to greet their visitors. Inside, visitors used flashlights to view the objects displayed in a darkened room with newspaper-filled coal bags lining the ceiling.

The onset of World War II prompted a significant shift in the surrealism movement. Many of its major contributors moved to the United States, causing the forties to be deemed a period of surrealism in “exile.” Beginning in the late 1930s, objects became increasingly prevalent features of surrealist exhibitions. The 1947 exhibition at the Maeght Gallery in Paris was prefaced by Breton’s characterization of assemblages of ordinary, everyday objects: “recent poetic and plastic works…have a power over minds that surpasses that of the work of art in every sense.” These exhibitions and their creators further distanced their objects from aestheticism of other artistic movements by utilizing esotericism. In the later International Exhibition of Surrealism at the Daniel Cordier Gallery in 1959-1960, Duchamp wanted to add the element of eroticism—the movement’s “most secret and constant inspirational power.” (“Surrealism and The Object.”) The exhibit included collages and ready-mades in playful, erotic constructions and incorporated objects such as umbrellas, sewing machines, and mannequin’s legs.

These exhibits do show a progression in the focus of surrealism. However, they support Sarah Elizabeth Harvey’s assertion that surrealism did not die with World War II and the American exile, but instead continued into the 1960s. According to Harvey, the late exhibitions forge a bridge between the historical avant-garde and the neo-avant-garde phases of modernist art. For example, neo-avant-garde artist Robert Rauschenberg interacted with surrealism through the medium of these exhibits. A key neo-Dada movement artist, he diverged from the ideas of many of his predecessors. Rauschenberg merged the realms of kitsch and fine art, entering new aesthetic territory that reiterated the Dada inquiry into the definition of art. Seemingly the modern successor of the surrealist objects’ movement, Rauschenberg used both traditional media and found objects in his works. Wanting his viewers to independently interpret his works, he left the placement and combination of his objects to chance so that there were no predetermined meanings within them. Though the surrealists were more intentional in their construction of collected objects, they too focused on the experience provided by their work rather than a prescribed meaning. Collective objects and compilations facilitate this focus by drawing attention away from specific pieces and instead toward the holistic creation and the sentiments it provokes. In this way, the collective objects and exhibitions of the surrealists have a persisting, durable impact in the realm of modernist art.