Sexualization of the Eye

In addition to imposing violence and physical alterations onto the eye, surrealist artists also transformed this body part by sexualizing its nature. Surrealists presented various interpretations of the sexual experience via photographs of sex professionals, images of the nude female form, manipulation of mannequins, and biographical accounts of intimate relations. For the purposes of this blog we have chosen to narrow our attention to the sexualization of the eye, rather than the body as a whole. This theme is evident from paintings, drawings, photographs, and literature. As we see will in the images of Toyen and René Magritte, some artists went so far as to replace the eye with body parts more commonly associated with the act of sex. There are often commonalities between this treatment of the ocular and the violation of the eye. In instances of violent imposition on the eye, surrealist artists often simultaneously transform its nature. In other words, one must look past the physical mutilation in order to see the deeper change of the essence of the eye as a body part. Other works offer a more superficial conflation of the eye with sexual organs: their images literally replace the eye with body parts directly associated with the act of sex.

In relation to the essential transformation of the eye, it is important to note that one of the core aims of the surrealist movement was to emancipate human desire (Tate). The first definition of the word desire is an intense want for something, but it is alternatively defined as “sexual appetite or sexual urge” (Collins). According to the surrealists’ vision, desire was central to “love, poetry, and liberty” and it was the “authentic voice of the inner self, and the key to understanding human beings” (Tate). André Breton proclaimed in his work “L’amor fou” that desire is “the sole motivating principle of the world, the only master humans must recognize” (Breton). Yet Breton also concedes to the power vision, describing the eye as an entity that “maintains an existence of its own, or at least exists profoundly enough to be distinctive” (Darya). Surrealists reconcile this tension by making the eye into an object to be controlled by humans rather than allowing the eye to remain as a human substance, thereby choosing desire of vision as their reigning force.

Erika also explores this process, stating “Bataille takes the eyeball and makes it into an object that has lost its original function of seeing, and is instead used for sexual pleasure, like a sex toy. Taking an object and robbing it of its original function by giving it a sexual pleasure purpose is seen very often in surrealist works” (Erika). I would extend Erika’s argument by saying that the surrealists not only changed the original function of the eye, but also altered its nature.As put by Darya, Breton also describes the eye as savage, implying that “this part of the body is particularly pure, untainted by civilization…wild and untamable” (Darya). Removing the agency of the eye and transforming it into a sexual object allowed surrealists to control its savage character, thus completely changing the innate qualities of the eye. By destroying the independent power of the sense of sight, surrealists free their desire from the influences of visual perception in order to engage sexual cravings that originate from the unconscious, rather than from reactions to visual stimulation occurring in conscious reality.

The power of the eye as an independent actor is also theorized by Georges Bataille in his article “The Pineal Eye”. He postulates, “the [pineal] eye, at the summit of the skull, opening on the incandescent sun in order to contemplate it in a sinister solitude, is not a product of the understanding, but is instead an immediate existence it opens and blinds itself like a conflagration, or like a fever that eats the being, or more exactly, the head” (Bataille, 1985 82). The pineal eye in this case does not refer to an actual eye ball, but to the pineal gland found in the center of the brain that was once coined as “the seat of the soul” by Descartes (Lokhorst). This expresses the paradox explained by Darya, in which the Surrealists view vision as an authority-in that is determines and shapes our reality-but it cannot be trusted (Darya). They seek a new portal for vision in the sense of enlightenment/unbridling of the unconscious. Bataille’s definition of the pineal eye offers this ideal alternative type of vision wherein the ‘eye’ is a reliable, powerful authority figure that reflects the images of the soul rather than the outside reality.

In the subsequent analyses I will highlight works in which surrealists replaced the eye with more typically sexualized body parts, then I will explore works in which we see the transformation of the eye’s nature described above. All of the following images evoke the feeling of the ‘uncanny’, as defined in Sigmund Freud’s 1919 aptly titled article “The ‘Uncanny’”. He asserts “the ‘uncanny’…belongs to all that is terrible-to all that arouses dread and creeping horror; it is equally certain, too, that the word is not always used in a clearly definable sense, so that is tends to coincide with whatever incites dread” (1). He continues, “it implies some intrinsic quality which justifies the use of a special name” (1). “The ‘uncanny’ is that class of the terrifying which leads back to something long known to us, once very familiar” (1-2).

The Eye takes a New Shape

René Magritte’s Le Viol (1934)*

This painting replaces human facial features for those of the torso, substituting the eyes with female breasts and the mouth with a vagina. The title of the piece, Lei Viol, implies that some act of violence is occurring, specifically sexual abuse. A human face is a familiar ‘object’ with distinct features that take one recognizable shapes and forms, despite the relative variety in appearances across the human species. By manipulating the familiar, Magritte penetrates the mind of the reader, penetrating the accepted range of what constitutes as a face and causing a the feeling of the uncanny.

Toyen’s Untitled drawing of a woman’s face (1931)*

Toyen’s untitled drawing of a woman’s face also has penetrative elements, but in a more obvious, tangible sense. The bird’s beak is literally penetrating the vagina, which has replaced the mouth of the face. Like Magritte’s painting, this image shatters all expectations of what constitutes a face. The act of poking or plucking out an eye is instinctually uncomfortable and unwanted, whereas the idea of penetrating the female organ or mouth is more acceptable, but the sight of a bird pecking a vagina located on the face is a new type of disturbing. It creates anticipation that the bird’s next target may be the eyes (vaginas), indirectly offending the viewer. Toyen creates layers of uncanny, first by obstructing and sexualizing the familiar physique of a face, and then by penetrating both the sensitive female organ and the audiences sensibilities.

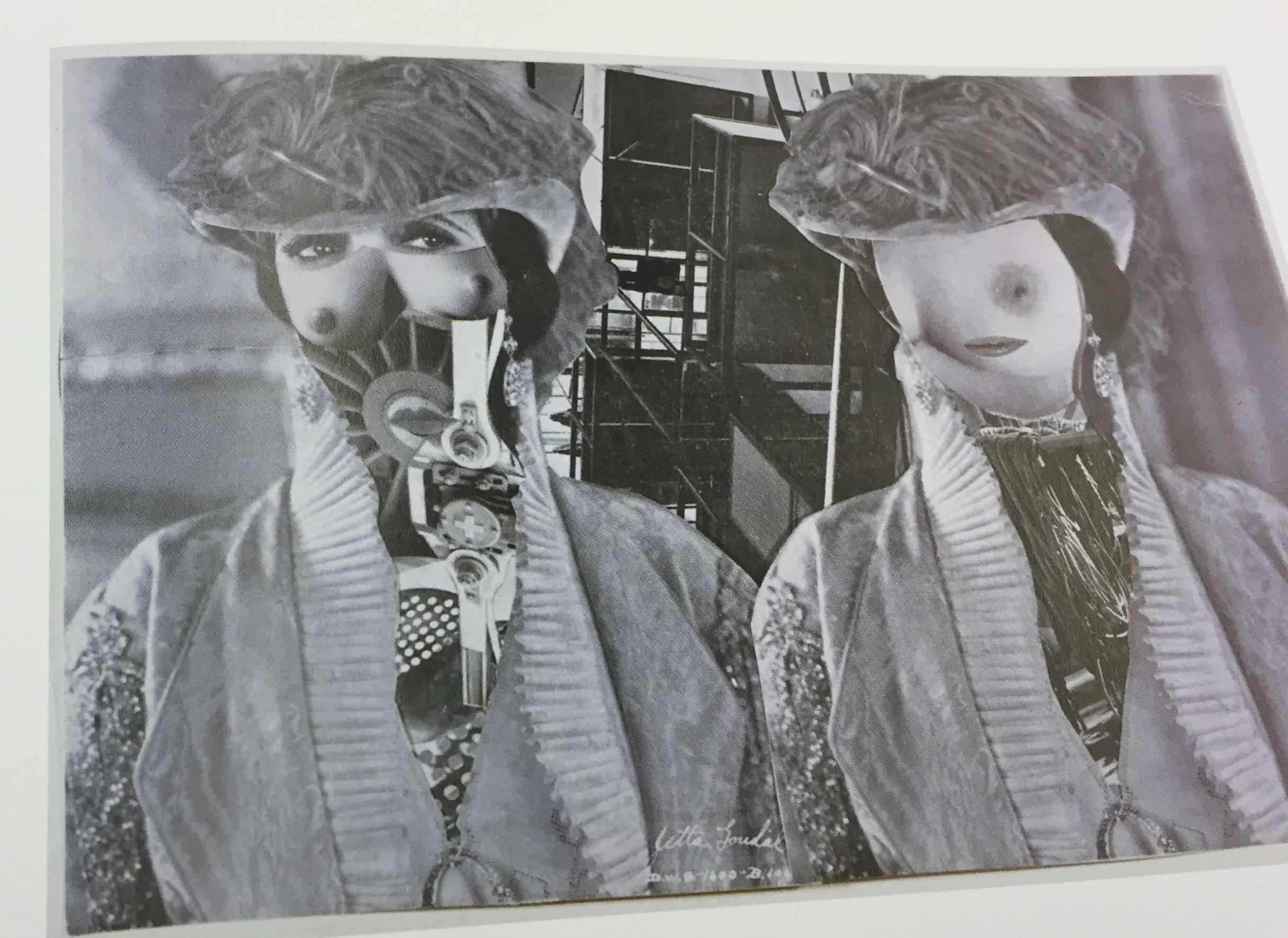

Karel Teige’s Untitled and Hans Bellmer’s illustration are not nearly as disturbing as the first two, but they similarly represent the surrealist trend of imposing sexual physical forms onto the face, specifically onto the eye. In Tiege’s collage, the eyes are still present in the left face, whereas the face on the right is a single breast with a small mouth placed at the bottom. Untitled seems more impersonal than Bellmer’s illustration, as if Teige has no relation to the subjects in his collage. This may be due to the gray scale of the image and the use of mechanical features to fill the space of the neck and chest. In this case, the eye is sexualized but it is not sensual or sexy.

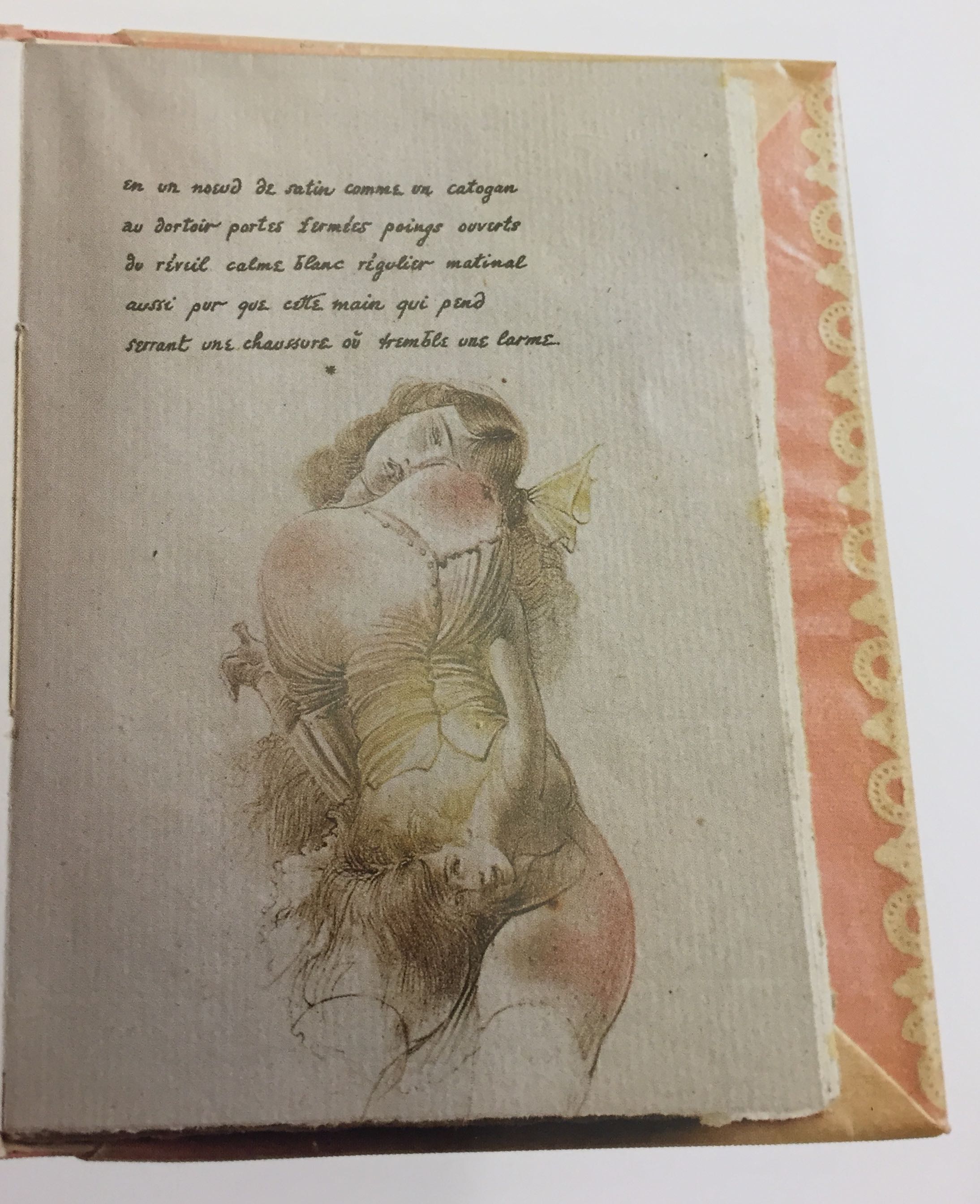

Bellmer’s drawing, however, appears to be drawn in the image of someone fond to the artist. The faces of the two women are certainly sexualized, indeed the entire positioning of the two figures is sexual, but the image maintains its softness and levity. One female is atop the other, with her bottom morphing into a breast that pushes against the other’s face, while the face of the first figure is aligned with the pubic area of the second. Despite the complexity of the illustration, my eyes are drawn to the eyes of the two women, which seem to express both the enrapturing pleasure of sex (the face at the top of the image) and the joy of sexually pleasing someone else (the bottom face).

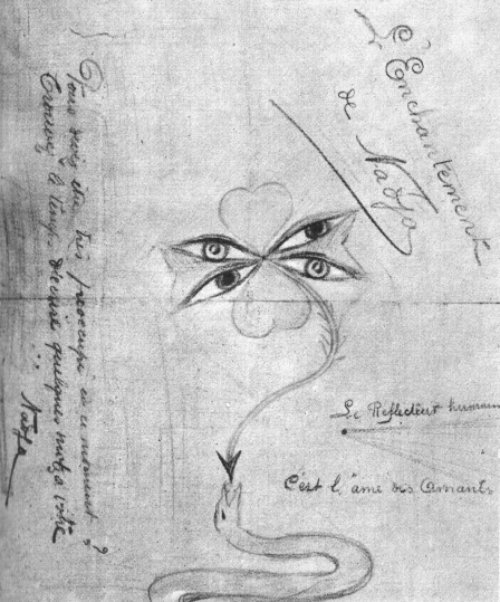

The Lovers’ Flower found in André Breton’s Nadja (1928)

In André Breton’s surrealist novel Nadja, we find among the numerous illustrations a compelling example of how the eye can be sexualized. He writes, “Nadja has invented a marvelous flower for me: ‘the Lovers’ Flower’. It is during lunch in the country that this flower appeared to her and that I saw her trying-quite clumsily-to reproduce it. She comes back to it several times, afterwards, to improve the drawing and give each of the two pairs of eyes a different expression” (Breton 116). The flower is a romantic meeting of two pairs of eyes, taking the shape of a natural object that already has sexual connotations. You may have heard the term “deflowered” used to describe the act of losing one’s virginity, and flowers are often employed as metaphors for female sexuality. This type of metaphor is not pertinent to the larger discussion of sexualization of the eye, but from common knowledge the viewer can understand the sexual connotations of flowers. The sharp stem and snake below the flower adds a phallic element to the drawing, increasing the sexual tones of the piece.

Secondary Qualities of the Eye associated with those of the Female Organ

Raul Ubac Untitled (1938)*

It serves the viewer well to analyze Man Ray’s photograph Larmes and Raul Ubac’s work in relation to each other because they represent the physical similarities between the eye and the female organ. Both the eye and the vagina are capable of producing moisture, and in a sense the vagina has its own form of tears, Ubac seems to comment on this by placing a gelatin teardrop onto the vagina in his piece. The viewer is invited to search for more commonalities between two organs that have starkly different functions for the body and society. By being compared to the vagina, the eye is debased from its simultaneously centric and elevated in society.

The Eye takes on a New Nature

In his chapter “The Deviations of Nature” from Visions of Excess: Selected Writings, Bataille invokes the theory of Pierre Boaistuau, “nothing is seen that arouses the human spirit more…that provokes more terror of admiration to a greater extent among creatures than the monsters, prodigies, and abominations through which we see the works of nature inverted, mutilated, and truncated” (Bataille, 1987 53). The works studied within this blog evoke this fear of the perverted natural.

Man Ray Minotaur

Man Ray Minotaur (1934)*

Man Ray’s photograph executes similar trickery as the images from Magritte, Teige, and Bellmer, portraying the female human torso as the head of a minotaur by way of cropping techniques and lighting manipulation. The raised arms become the horns of the beast and the breasts appear as the eyes, clearly the focal point of the image. This photograph personally does not evoke the Freudian feeling of the uncanny, perhaps because the face of the minotaur is not an object of familiarity for me. The image remains striking and atypical, but it does not violate the sense in the same way as Le Viol. Most resonant is the softness of the image despite the beastliness it is meant to represent. Man Ray has ultimately feminized an archetypally male creature, thereby changing the sexual nature of the object. However, this is in contrast to the transformations we will explore in Story of the Eye and Manhood because, as we learned in class, the minotaur was sexualized in his original myth. Yet in Bataille’s and Leiris’ works, the eye is not innately sexual until the author manipulates it. The eye’s original role is as previously described by Breton: it is an independent, savage agent, untainted by civilization.

Manhood Michel Leris

Surrealist author Michel Leiris recounts the childish games he played with his sister in his literary self-portrait Manhood, one of which involved being blindfolded and guided to ‘put one’s finger through someone’s eye’. He writes, “You blindfold the one who is ‘it’ and tell him you’re going to make him ‘put someone’s eye out’. You lead him, index finger extended, toward the supposed victim, who is holding in front of this eye an egg cup filled with moistened bread crumbs. At the moment the forefinger penetrates into the sticky mess, the supposed victim screams. I was ‘it’, and my sister the victim. My horror was indescribable” (46). We then are able to glean that Leiris’ horror stems from his association of the eye with female genitalia. thus to penetrate the eye is to penetrate the female organ. He confesses, “The significance of the ‘eye put out’ is very deep for me. Today I often tend to regard the female organ as something dirty, or as a wound, no less attractive for that, but dangerous in itself, like everything bloody, mucous, and contaminated” (Leiris 46).

The shared mucous qualities of the eye and vagina level their status in Leiris’ eyes: they are two tainted objects capable negatively affecting his life. Here we see the sexualization of the eye as a basic transformation, not a superficial change. The eye loses its agency, but it is still viewed as something that cannot be controlled, hence the potential for danger from dirt, mucous filled objects like the eye and vagina. In her work Surrealism, Feminism, and Psychoanalysis, Natayla Lusty explicates Leiris’ type of terror in relation to a different surrealist art piece. She writes, “Un chien andalou signals an acute agressivity by the male desiring subject against the body of the desired object, so that the violation of the eye, the organ of desire and identity, produces an annihilation that registers the seductive terror of the love object” (52). Leiris’ childhood experiences embody this phenomenon, for he displays agressivity towards what he believes to be an eye. He is uncomfortable with the desire the vagina sparks inside himself, and he also fears the act of giving in to the love object, to the end of penetrating its form and experiencing its wet danger.

Georges Bataille Story of the Eye

The fear of the female organ and they eye expressed by Leiris is entirely absent from Georges Bataille’s singular work Histoire de l’Oeil or Story of the Eye. As aptly put by Martin Jay in his article “The Disenchantment of the Eye: Surrealism and the Crisis of Ocularcentrism.”, an important implication Bataille’s novel is “whether understood literally or metaphorically, the eye is toppled from its privileged place in the sensual hierarchy to be linked instead with objects and functions more normally associated with “baser” human behavior. This is, indeed, the most ignoble eye imaginable” (18). He also notes. “the eye in this story, to borrow Brian Fitch’s phrase, l’oeil qui ne voit pas” (18).

Bataille wants a reversal of Freud’s claim found in Civilization and its Discontents, “human civilization…only began when hominids raised themselves off the ground, stopped sniffing the nether regions of their fellows and elevated sight to a position of superiority. With that elevation went a concomitant repression of sexual and aggressive drives, the radical separation of “higher” spiritual and mental faculties from the “lower” functions of the body” (19).

Enucleation is a theme of the work, graphically represented in Chapter 10, “Granero’s Eye”, and Chapter 13, “The Legs of the Fly”. Chapter 10 is a reproduction of an actual event Bataille witnessed in 1922, which was the bullfight where a bullfighter was stabbed trough the eye by the bull’s horn (Bataille 74). Chapter 13 is a fictional recounting of murderous sexual escapades that resulted in removing the eye of a priest and using it as an object of sexual pleasure. The narrator and his lover Simone are the main figures of the work, and Simone initiates the enucleation in this final chapter (94). After sexually abusing and killing the priest, Simone proceeds to fetishize his eye, begging the narrator to let her play with it (94). She inserts it into her body, and the narrator explains his reaction to this sight, “Now I stood up and, while Simone lay on her side, I drew her thighs apart, and found myself facing something I imagine I had been waiting for in the same way that a guillotine waits for a neck to slice. I even felt as if my eyes were bulging from my head, erectile with horror; in Simone’s hairy vagina, I saw the wan blue eye of Marcelle, gazing at my through tears of urine” (96). Marcelle is a former lover of Simone and the narrator whom they obsessed over. Here we return to the concept of horror at associations of the eye with the vagina, the particular type of horror being the uncanny feeling described by Freud. The eye is familiar to the narrator, and it perhaps was always sexualized in the sense that it is part of the body of their former sexual partner, but its removal from its natural location and exploitation as a completely sexual object that evokes the uncanny. The eye no longer controls desire, but is an object through which the characters can fulfill their desires.

Also relevant are the thematic transformations on which the story’s characters fetishistically focus. Throughout the story, eggs, testicles and the sun are linked to the eye, as are the liquids associated with them (tears, egg yolks, and sperm) (Bataille 107). In the second part of the work, Bataille explains the possible inspirations for his novel, retelling his memories of watching the expression of his father’s eyes when he urinated, the whiteness of which he directly linked to “the image of eggs and that explains the almost regular appearance of urine each time eyes or eggs occur in the story (107).

Barthes also comments of Bataille’s work in his critical essay “Metaphor of the Eye”, asserting, “it is the very equivalence of ocular and genital which is original…everything is given on the surface and without hierarchy, the metaphor is displayed in its entirety; circular and explicit, it refers to no secret” (241). I am in agreement with Barthes, and of the works studied in this blog, The Story of the Eye is the most complete transformation of the eye into a sexual object. It violently removes the eye’s independent power and rejects the superiority of vision in favor of the dominance of desire.

*This image was found in Surrealism: Desire Unbound.