The German chemist, Justus von Liebig (1803-1873), made major contributions to agricultural and organic chemistry, and is regarded as one of the greatest chemistry teachers of all time. In addition to his academic work, he invented a way of producing beef extract from carcasses, which could provide a cheap, nutritious alternative to real meat (we know this today as beef bouillon). In 1865, Liebig formed the Liebig Extract of Meat Company and, like many companies at the time, had a number of trade cards printed to advertise his business. More than 1,900 Liebig cards have been documented, containing pictures of animals, landscapes, or portraits of historical figures along with the company logo.

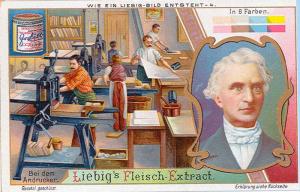

The graphic arts collection holds a large group of late 19th- and early 20th-century trade cards, among them one 1906 set of cards for Liebig’s company entitled Wie ein Liebig-bild entsteht. Each of the six cards depict one segment of the process of making chromolithographs, and the entire set is beautifully printed by chromolithography. Although I’m sure the Liebig extract of meat was very tasty, it is the views of chromolithographic process that make these cards of value to our collection. To see a wonderful exhibition on chromolithography, visit the Museum of Printing in Lyon, France, or their website: http://www.imprimerie.lyon.fr/imprimerie/sections/fr/expositions

Lithography was developed in the 1790s, as a convenient way to reproduce an image drawn on a flat, stone surface rather than carved from a wood block or cut into a metal plate. A picture or text is drawn with a greasy crayon onto a flat surface and then, the surface is chemically treated so that the drawn areas attract ink and the rest of the stone repels it. In this way, a drawing can be inked and printed many times to produce a number of sheets with the same image.

Color prints are created by printing many different stones, inked in different colors, onto a single sheet. In chromolithography, overlapping colors of oil-based inks create a thick, relief surface meant to replicate the look of an oil painting. Although “chromos” could be mass produced, it can take about three months to draw colors onto the stones and another five months to print a thousand copies.

The first American chromolithograph is a portrait of Reverend F. W. P. Greenwood, printed by William Sharp in 1840. The Graphic Arts collection is fortunate to hold the first American book illustrated with chromolithographs: Morris Mattson (1809?-1885), The American Vegetable Practice, or, A New and Improved Guide to Health, Designed for the Use of Families (Boston: Published by Daniel L. Hale …, 1841). The volume contains 26 plates; 24 are chromolithographs drawn by Sharp, Mattson, Miss C. Neagus, and Mrs. Anne Hill, and printed by Sharp, Michelin & Co. [Graphic Arts Collection (GAX) 2007-1967N]