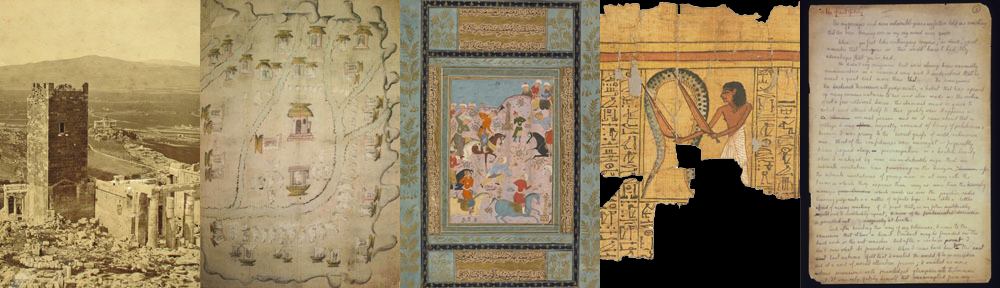

The Peck Shahnamah, on display in the exhibition “Princeton’s Great Persian Book of Kings,” at the Princeton University Art Museum (October 3, 2015-January 24, 2016), is among the most treasured books in the Manuscripts Division. But the Manuscripts Division holds five additional illuminated Shahnamah manuscripts and hundreds of other Persian and Mughal illustrated manuscripts and miniatures, among nearly ten thousand Islamic manuscripts. Approximately two-thirds of these were part of the 1942 donation of Robert Garrett (1875-1961), Class of 1897. One aspect of Persian book arts that has not previously received much attention, at least with regard to Princeton’s extensive collections of Islamic manuscripts, is the Persian lacquer binding. The Manuscripts Division holds dozens of examples, several of which are featured in a recent article by Lindsey Hobbs, Collections Conservator, Preservation Office: “Persian Lacquer Bindings,” The New Bookbinder: Journal of Designer Bookbinders, vol. 35 (2015), pp. 49-56.

Persian lacquer bindings first developed in the fifteenth century and reached their height of popularity in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. These bindings most commonly feature elaborate floral designs, like the upper cover of the Qur’an illustrated below. But examples at Princeton also feature animals, birds, braid patterns, mandalas, ringlets, rosettes, and fleurons. Their inclusion was the result of the influence of cultural contact as Islam spread east and west from the seventh century. The first step in producing a lacquer binding, typically, is to prepare the pasteboard covers for painting by applying a layer of gesso; that is, a white mixture of a binder and chalk, gypsum, pigment, or a combination of these ingredients. After this application comes an initial coat of varnish. Water-based paint is used to create a painting or design, which is coated with several additional layers of varnish. The surfaces are then smoothed and polished. In some cases powdered mother-of-pearl, gold particles, or other inlay materials are added to the varnish before drying. There are also lavish early examples that combine decorated leather with lacquer painting. The result is a brilliant sheen that gives Persian lacquer bindings a distinctive character.

One of the more notable examples at Princeton dates to 1520 CE. The Dīvān-i Hāfiz, a well-known anthology of Persian classical poetry, features a symmetrical array of flowers, birds, and animal heads surrounding a central eight-pointed star. The cover design reveals inspiration from the Far East, possibly a vestige of the Mongol invasions from earlier centuries. The book has orange leather doublures, highly decorated with gilt. The richly illuminated text is written in Nasta’līq, a calligraphic script often used for deluxe Persian manuscripts, and contains six full-page miniatures. While the manuscript was likely resewn and given a new spine at some point in its history, this is one of very few examples of lacquer bindings that seems likely to have retained its original covers.

For more about Persian lacquer bindings, see Lindsey Hobbs’s article in The New Bookbinder, a journal in the Firestone Library’s circulating collections. There are Voyager bibliographic records for each of the manuscripts illustrated in her article. For information about Islamic holdings in the Manuscripts Division, contact Public Services.

Qur’an (upper cover),

Islamic Manuscripts,

New Series, no. 1984,

Manuscripts Division.

You must be logged in to post a comment.