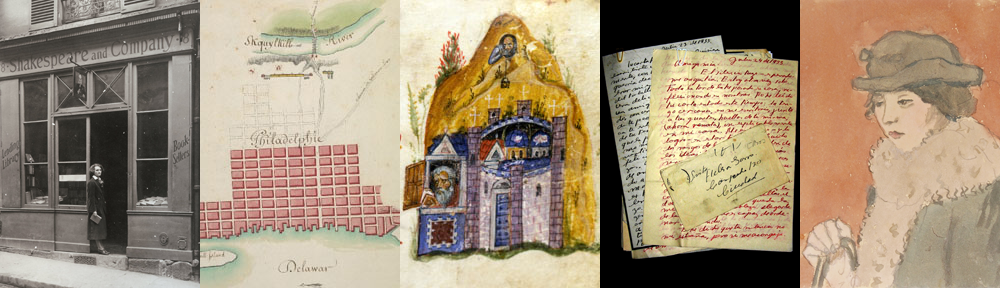

Every old manuscript, however fragmentary, has a story to tell. And such is the case with Garrett Hebrew MS. 4. Robert Garrett (1875-1961), Class of 1897, one of the Princeton’s most celebrated collectors, donated it to the Library 75 years ago as part of the extensive Garrett Collection. Long overlooked, the two parchment strips (see images below) appear to be remnants of a lost 16th-century Hebrew pilgrimage scroll, probably brought back from the Holy Land by a Jewish pilgrim. The fragments depict Temple utensils (sometimes called Sanctuary implements) used in religious ceremonies at Jerusalem’s ancient Temple; as well as the recommended itinerary for other Jewish sacred places in the Holy Land. Images of the Temple and its sacred implements had been depicted on illuminated double-pages bound into deluxe Hebrew Bibles from Castile, Catalonia, and Perpignan between the 13th and 15th centuries. These visualizations have been interpreted as representing the Messianic hopes of the Sephardic Jews in the Iberian Peninsula, when they began to face Christian persecutions and proselytizing during the final centuries of the Reconquista. The Garrett Hebrew scroll was informed in part by such imagery yet belongs to a later book tradition.

In the second half of the 16th century, Jewish scribes and book artisans in Jerusalem and Safed, under Ottoman Turkish rule, began to custom produce Hebrew pilgrimage guides on parchment scrolls for the growing numbers of Jewish travelers to the Holy Land. No doubt, some were Sephardic Jews, whose families had fled the Spanish Inquisition and forced conversion. Several pilgrimage guides were definitely brought back to Italy as souvenirs, and a few most likely served as models for similar guides produced in Italy. Most of the seven extant pilgrimage guides are configured like medieval scrolls; that is, reading from top to bottom in one long column. This is the form of two well-preserved pilgrimage scrolls at the Jewish National University Library (nos. 1187 and 6947), respectively 140.0 cm and 219.0 cm in length. The first of the two was in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s recent exhibition Jerusalem, 1000-1400: Every People under Heaven. They each have substantial text accompanying stylized images. Clearly, not all the holy places and objects were still extant or could actually be visited by Jewish travelers. Scroll producers did not hesitate to show the Dome of the Rock, topped by a crescent, as a stand-in for the Second Temple. But even when a physical visit was impossible, these scrolls could still serve far-flung Jewish communities in Europe and the Near East as visual reminders of sacred places and objects. Rolling them out for wall display or table-top consultation offered a virtual pilgrimage.

Garrett Hebrew MS. 4 is somewhat different than the best-known Hebrew pilgrimage scrolls of that era. To judge from what survives, which is perhaps a third to a half of the scroll’s original length, the text is more limited and the images not well executed. Moreover, it was configured in the form of a classical scroll, being unrolled and read from right to left, as were Torah scrolls and small-format scrolls of particular Hebrew Books of the Bible, intended for use on specific holidays: Ecclesiastes (Sukkoth), Book of Esther (Purim), Book of Ruth (Pentecost), The Song of Songs (Passover), and Lamentations (Ninth of Av). The small size of pilgrimage scrolls made them portable. Jewish pilgrims could easily transport them in a leather or fabric sack. Equally portable was a small codex, such as one produced in 1598 for a member of the Jewish community of Casale Monferrato, in northern Italy (Leeds University Library, Roth MS. 220). But scroll format had the advantage of laying out the entire itinerary in a straight line.

Mounted together, the two fragments of Garrett Hebrew no. 4 depict sacred places and objects as stylized illustrations, executed in iron-gall ink and red tempera, and individually labeled in Hebrew. Section A (12.7 x 41.5 cm) relates to the Temple of Jerusalem (right to left): Two Shofars, below which is the Ark of the Covenant, containing the Ten Commandments, each tablet with an abbreviated title; forceps for rites; the Altar of Sacrifice and Stairs; Menorah; Foundation Stone (checkerboard design, called The Drinking Stone); Shim’i the Ramati (or Place of our Lord) with hanging oil lamps. Section B (12.4 x 45.5 cm) includes scenes outside Jerusalem (right to left): Cave of Machpelah (near Hebron), which Abraham bought for the burial of Sarah and which came to serve as the burial place for the patriarchs and matriarchs; an unidentified cave identified as the Three Wells of Stone; Tomb of Rachel, with double arch, located between Jerusalem and Bethlehem; Tomb of Zechariah, an ancient rock-cut stone monument in the Kidron Valley.

Garrett Hebrew MS. 4 is also reproduced in Rachel Sarfati, ed., Offerings from Jerusalem: Portrayals of Holy Places by Jewish Artists (Jerusalem, The Israel Museum, 2002), pp. 48-49. For further reading on pilgrimage scrolls and imagery, see Bianca Kühnel, “Memory and Architecture: Visual Construction of the Jewish Holy Land,” in Doron Mendels, ed., On Memory: An Interdisciplinary Approach (Bern: Peter Lang, 2007), pp. 177-93, figures 8.1, 8.2; Eva Frojmovic, “Messianic Politics in Re-Christianized Spain: Images of the Sanctuary in Hebrew Bible Manuscripts,” in Imagining the Self, Imagining the Other: Visual Representation and Jewish-Christian Dynamics in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Period, edited by Eva Frojmovic (Leiden: Brill, 2002), pp. 91-128; Eva Frojmovic and Frank Felsenstein, Hebraica and Judaica from the Cecil Roth Collection (Leeds: Brotherton Library, University of Leeds, 1997), pp. 16-17, no. 5. Special thanks to Professor Susan Einbinder, University of Connecticut, for deciphering the inscriptions in Garrett Hebrew MS. 4.

Garrett Hebrew MS. 4

You must be logged in to post a comment.