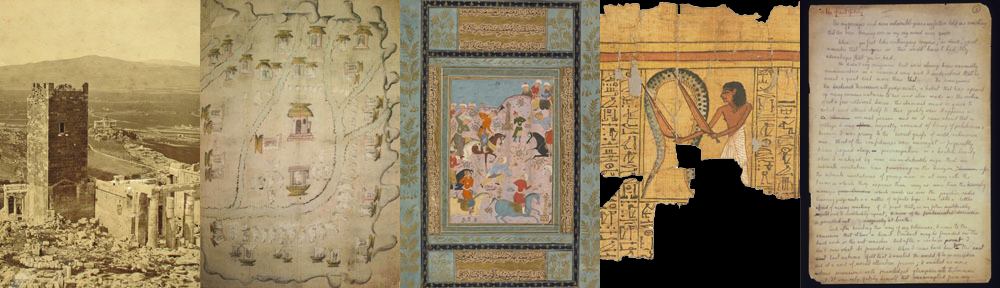

The chance survival of autograph manuscripts by unknown women of centuries past can help to illuminate their lives and times, innermost thoughts, and writing methods. Looking back at England in the 17th century, in addition to well-known authors such as Aphra Benn and Katherine Philips, there were obscure women writers yet to be discovered. A case in point is an abridged history of medieval England by a certain Susan Pigott (RTC01, no. 238), probably writing early in that century. Her 104-page manuscript, recently acquired by the Manuscripts Division, begins with a signed dedicatory letter to the king of England, filled with tantalizing autobiographical details. Pigott describes herself as a “poore oppressed widdowe,” with two children. Her late husband, Pigott wrote, had rendered “dutiful and dangerous services faythfully accomplished to your heighnes. And this our native countrey, in a forrayne nation, whereby he lost his life.” Since his death, perhaps two and a half years earlier, Pigott claims to have been a victim of “rare opressions and hevy injuries outrageously heaped upon me and myne agaynst all good order of law and like course of justice usual in any Christian Commonwealth.” She even mentions “secrett papers … penned from tyme to tyme” for royal use. Pigott’s signed but undated letter prefaces a summary history of the kings of England, from William the Conqueror to Henry VII. Pigott wrote and corrected her manuscript in English Secretary hands of the early 17th century, consistent with those illustrated in Martin Billingsley’s writing manual, The Pens Excellencie or the Secretaries Delighte (1618). The paper has a heraldic watermark dating from around the same year: a shield with the arms of Strasbourg and fleur-de-lys; below the shield is a terminal flourish “WR,” which in the 16th century had stood for Wendelin Riehel but continued to be used and imitated in later centuries. If Pigott’s epitome is contemporary with the script and paper, then the king in question should be James I (r. 1603-25).

Pigott describes her work as “a shorte sumanary [sic] of examples of youre majesties most noble progenitors, royall kings of this your heighnes realme sethens [i.e. since] the last conquest.” She compiled her epitome by paraphrasing (her operative word is “collected”) scattered bits of text from Raphael Holinshead (1525-80?), Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland (1577), a collaborative multi-volume history. Pigott only used the four volumes relating to England and added Holinshead folio references in the margins. This popular work is best known today because William Shakespeare used the 1587 second edition of Holinshead as a source of information for King Lear, Macbeth, and various history plays (such as Richard III). Yet the identity of Susan Pigott is uncertain. The Pigott surname (with variant spellings) is of Norman origin and not unusual in England. British public records identify various widowed women named Susan Pigott. Among them is one who was a plaintiff in 1578-79 in a law suit involving a certain John Walton, Richard Groffield, Thomas Southern, and others; and another who in 1658 presented the curate Elnathan Pigott (d. 1675/76) to the Church of St. Marie, Bury St. Edmunds, Suffolk. But neither Susan Pigott can be connected with the author of the present manuscript, and more research will be needed to identify her. There is no way to know if she actually presented it to the king. What we do know is that the manuscript was in various English and Irish libraries, including those of Nathaniel Boothe, 1747; Thomas Connolly, 1860; and Frederick William Cosens, 1890. The manuscript came to the Library in desperate need of conservation treatment. The Library’s Book Conservator, Mick LeTourneaux, has now completed that work.

The Robert H. Taylor Collection of English and American Literature has two other autograph manuscripts by English women of the 17th century. The best known is My Booke of Rememberance by Elizabeth Isham (1608-54), an autobiographical work written around 1638, when she was about thirty. She was the daughter of Sir John Isham and once fianceé to John Dryden. In Isham records her fervent religious beliefs and inner thoughts, while living at Lamport Hall, her family’s Northamptonshire home (RTC01, no. 62). Isham’s manuscript has been digitized and is available online in DPUL (Digital Princeton University Library). An online edition is available from the University of Warwick. Another autograph memoir in the Taylor Collection is that of Mary Whitelocke (b. 1639), dating from the 1660s and bound in a contemporary embroidered binding (RTC01, no. 226). Whitelocke’s memoir is an intimate and detailed account of a wealthy Puritan gentry woman, whose father was a London merchant. Addressed to her eldest son, Whitelocke’s memoir encompasses her life from the time of her first marriage at age sixteen to Rowland Wilson (d. 1650), a Member of Parliament, also from a London mercantile family. Whitelocke’s second marriage in 1650 was to the prominent lawyer and politician Bulstrode Whitelocke (1605-75), with whom she had seven children. The memoir often focuses on Whitelocke’s family and domestic affairs, though discussion of public affairs and events is also in evidence, particularly in connection with her second husband’s public life. For more information, contact Public Services, rbsc@princeton.edu

You must be logged in to post a comment.