These days, Aaron Burr, Jr. (1756-1836), Princeton Class of 1772, is chiefly remembered as the man who, while serving as the third Vice President of the United States (1801-5), mortally wounded Alexander Hamilton in a duel (1804). Burr’s career in public life all but ended with the duel at Weehawken, New Jersey. Sometimes forgotten, however, is Burr’s earlier distinguished service as a Continental Army officer during the Revolutionary War and his subsequent career as a busy New York City attorney and litigator. He moved there in 1783 to practice law and would handle cases of every conceivable description, including some involving the city’s more than two thousand slaves. As part of ongoing efforts to expand holdings on African American history, the Manuscripts Division has just acquired Aaron Burr’s signed legal complaint in the Mayor’s Court (9 August 1784) relating to his legal client, William Stevenson, a local auctioneer, whose woman slave had been taken “craftily and subtlely” by a certain John Lake, alleged to have “converted and disposed of the said Negroe woman slave to his own proper use to the damage of the said Thomas of eighty pounds.” This was one of three slave cases handled by Burr in 1784, according to Nancy Isenberg’s Fallen Founder: The Life of Aaron Burr (2007). At the time, Burr was a slaveholder, yet surprisingly he also favored the abolition of slavery and opposed restrictions on the rights of New York’s free blacks. The document has been added to the Aaron Burr (1756-1836) Collection (C0089).

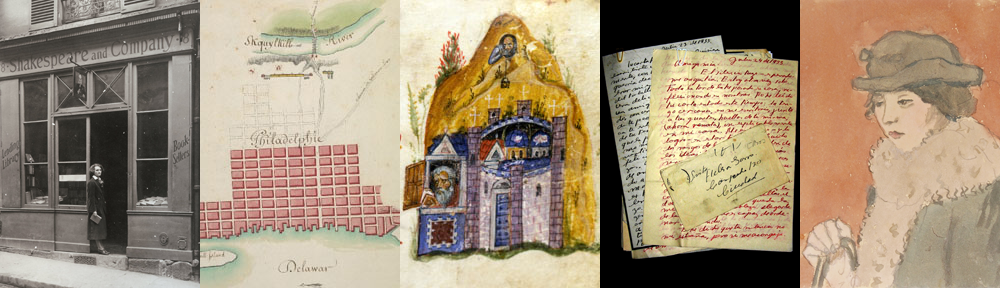

Other recent acquisitions include documents pertaining to the African slave trade and African Americans from slavery to freedom. The oldest is a slim volume of sailing directions for an unnamed English ship trading between the “slave coast” of West Africa and the Caribbean, 1760 (C1210).Added to the same open collection of documents were other items, such as a New Jersey slave bill of sale for a boy named Harry, sold by John Dixon, of Morristown, to Shubal Pitney, of Mendham, 1797 (see image below); a note concerning a runaway slave in Carroll County, Maryland, ca. 1817; a letter from James Holladay to William Langhorne, of Portsmouth, Virginia, discussing an advertisement for the sale of a slave girl, 1820; an order for the arrest and whipping of a black slave named “Negro Frank,” who was accused of insulting and striking John Kelly, a white man, 1851; and a slave bill of sale for five black men in Vicksburg, Mississippi, 1857. The Hooe Family Papers is a separate collection (C1628) relating to a slave plantation in Prince William County, Virginia, 1829-50. Finally, the Manuscripts Division acquired a complete set of eleven Civil War muster rolls (1864) for U.S. Colored Troops, 39th Infantry Regiment and ten of its companies (C1626). Most of the black troops were from Baltimore and its environs, supplemented by others from other places. The regiment saw action in Virginia under the command of Colonel Ozora Pierson Stearns. Among the troops was Sergeant Decatur Dorsey, an African American honored for his actions at the Battle of the Crater (30 July 1864) and later settled in the town of Hoboken, less than two miles south of the Burr-Hamilton duel site.

Previous blog posts have surveyed holdings on the African slave trade and slave society in the Americas. For more information about recent additions, contact Don C. Skemer, Curator of Manuscripts, dcskemer@princeton.edu

New Jersey Slave Bill of Sale, 1797.

You must be logged in to post a comment.