By Emma M. Sarconi, Reference Professional for Special Collections

In early March 1957, “at the urgent request of Mr. William S. Dix” (Princeton University Librarian), educator and dramatist Emily Hale drafted a review of her relationship with poet T.S. Eliot to accompany the collection of letters she donated to the Princeton Library in 1956. Completed in 1965 with the editorial support of Dix, and her long-time friends Princeton English Professor Willard Thorp, and journalist Margaret Thorp, she chronicled her relationship with the famous poet, describes the “unnatural code that surrounded us” as well as expressed her hope that through the letters’ release “at least the biographers of the future will not see this ‘a glass darkly’ but like all of life ‘face to face.’”

Upon learning of Hale’s donation of his letters to Princeton, T.S. Eliot drafted his own review of his relationship with Hale. That text can be found on Harvard’s Houghton Library Blog (see here).

Per the agreement Hale made with the library upon her donation, the material in the Emily Hale Letters from T.S. Eliot had been sealed for fifty years following her death. On January 2, 2020, these items were made publicly available and are now open to view by all patrons. For more information on the release of these materials, please see the blog post drafted by the former Curator of Manuscripts, Don C. Skemer.

For more information on the contents of the collection, please view the collection finding aid. For more information on visiting the Special Collections Department in Princeton, please see the library website or email RBSC@princeton.edu.

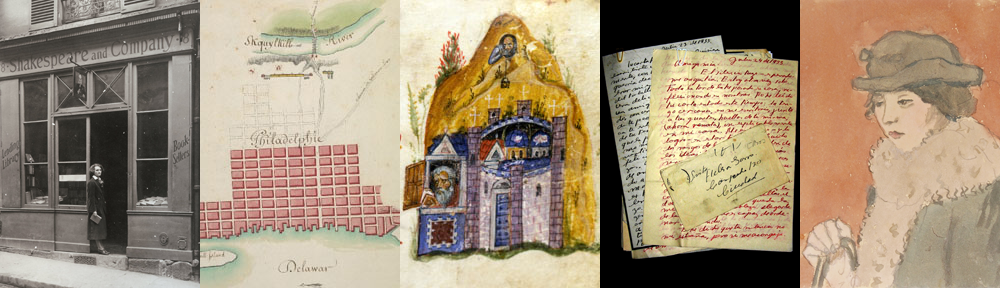

Below, please find images of the final draft of Hale’s three-page narrative followed by a textual transcription. TIFF images of previous drafts as well as some of Hale’s correspondence with Dix, can be found here.

At the urgent request of Mr. William S. Dix, currently Librarian of Princeton University Library, and my long-time friends, Professor and Mrs. Willard Thorp of Princeton (Professor Thorp is a prominent member of the English Department of the University), I am writing this brief review of my years of friendship with T. S. Eliot.

We knew each other first in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he was working on his graduate course preparatory to completing his doctorate in philosophy. He left in 1913 for such preparation in Germany. Before leaving, to my great surprise, he told me how very much he cared for me; at the time I could return no such feeling. His subsequent life in Oxford and later citizenship in England are known by many and everyone who studies his work. At the close of the war he married an English girl whom he had met at Oxford. This marriage was a complete surprise to his family and friends and for me particularly, as he had corresponded quite regularly with me, sent flowers for special occasions, etc.; I meanwhile trying [sic] to decide whether I could learn to care for him had he returned to the “States”.

We did not meet until the summer of 1922, when I was in London with my aunt and uncle. His marriage was already known to be a very unhappy affair which was affecting both his creative work and his health. Only his closest friends at this time knew fully of the miserable relationship between his wife and him. Knowing this, I was dismayed when he confessed, after seeing me again, that his affection for me was stronger than ever, though he had assumed years of separation from his home in America and old friends would have changed his attitude toward me. From this meeting in London until the early 30’s I was the confidante by letters of all which was pent up in this gifted, emotional, groping personality.

He was finally legally separated from his mentally ill wife. That they were never divorced was due to his very strong adherence to his conversion to the Anglo-Catholic Church.

Up to 1935, between trips to America and correspondence, we saw each other and knew about each other’s life – though I had no feeling except of difficult but loyal friendship. I taught during these years at private schools or girls’ colleges; he was becoming more and more acclaimed in the world of letters, everywhere.

Hiw [sic] wife was finally committed to an institution, leaving him emotionally freer, at least, than in many years. From 1935 – 1939, under this change in his life, he came each summer to stay in Compden, Gloucestershire, for a week or so, with my aunt and uncle who rented a charming 18th century house in the town – and to which I came for the whole summer to help my aunt in her entertaining and greatly enjoy the days in the lovely Cotswold village. On one of his visits, we walked to nearby “Burnt Norton” – the ruins of an 18th century house and garden. “Burnt Norton”, as Tom always said, was his “love poem” for me. My relatives knew the circumstances of T.S.E.’s life, and perhaps regretted that he and I became so close to each other, under conditions so abnormal, for I found by now that I had in turn grown very fond of him. We were congenial in so many of our interests, our reactions, and emotionally responsive to each other’s needs; the happiness, the quiet deep bonds between us made our lives very rich, and the more because we kept the relationship on as honorable, to be respected plane, as we could. Only a few – a very few – of his friends and family, and my circle of friends knew of our love for each other; and marriage – if and when his wife died – could not help but become a desired, right fulfillment. To the general public, and our friends in England and America, I was only “his very good friend”.

Vivian Eliot died in the mid 40’s, at the close of the war, but instead of the anticipated life together which could now be rightfully ours, something too personal, too obscurely emotional for me to understand, decided T.S.E. against his marrying again. This was both a shock and a sorrow, though, looking back on the story, perhaps I could not have been the companion in marriage I hoped to be, perhaps the decision saved us both from great unhappiness I cannot ever know.

We met under these new difficult circumstances on each of the visits he continued to make to this country for personal or professional reasons. The question of his changed attitude was discussed, but nothing was gained by anyffurther [sic] conversation. However, in these years before his second marriage, he always came to see me, was gentle, and still shared with me what was happening to him, or took generous interest in speaking at the school where I then taught.

The second marriage in 1947 I believe took everyone by surprise. He wrote of it to two persons in this country, his sister Marian, and me. I replied to this letter, also writing to Valerie. I never saw T.S.E. nor ever met her after this marriage, although they came to Cambridge two or three times to be with his family and friends, as well as to deliver lectures or give readings.

I can truthfully say that I am both glad and thankful his second marriage brought him the great comfort and remarkable devotion of Valerie; everyone who knew her testified to her tireless care of him, as his health grew worse; his family were delighted with her. The memory of the years when we were most together and so happy are mine always and I am grateful that this period brought some of his best writing, and an assured charming personality which perhaps I helped to stabilize.

A strange story in many ways but found in many another life, public and less public than his. If this account will keep the prying and curiosity of future students from drawing false or sensational conclusions I am glad. After all, I accepted conditions as they were offered under the unnatural code which surrounded us, so that perhaps more sophisticated persons than I will not be surprised to learn the truth about us. At least, the biographers of the future will not see “through a glass darkly,” but like all of life, “face to face.”

(s) Emily Hale

N.B. With the retirement of Curator of Manuscripts Don C. Skemer in November 2019, various Special Collections staff members will author blog posts on manuscript collections at Princeton.

Pingback: Song about ‘A Strange Story’: The Love Song of T. Stearns Eliot love - Love Songs