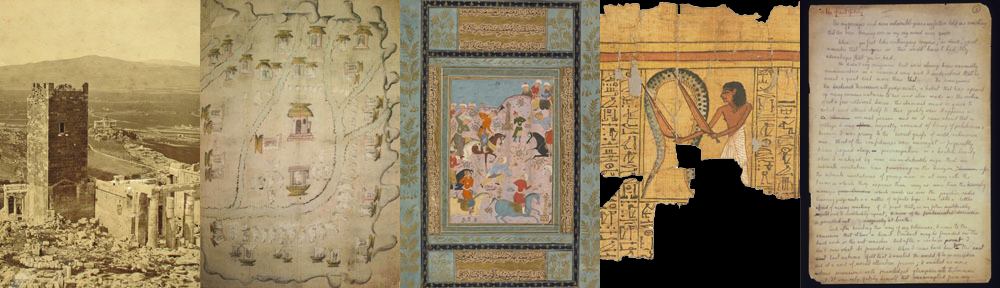

Armenian manuscripts have long been studied by medieval art historians for the quality of the book production, elegant script, distinctive illumination, vividly colored decoration, and original or treasure bindings (when extant). The Princeton University Library is fortunate to have a small but fine collection of Armenian manuscripts, dating from the 11th to 18th centuries. Most are in the Manuscripts Division, including those in the Garrett Collection of Armenian Manuscripts, which was part of the great 1942 donation by Robert Garrett (1875-1961), Class of 1897. Reproduced below is a two-page opening from one of Garrett’s finest Armenian manuscripts, an exquisitely illuminated Gospel Book (1449), here open to Baptism of Christ (left) and the Last Supper (right). In the 1930s, Seymour DeRicci and W. J. Wilson, Census of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts in the United States and Canada (1935-40), included Armenian manuscripts among western manuscripts, no doubt because of the Byzantine influence on Armenian book illumination. But other artistic and cultural traditions played a role as well.

DeRicci, vol. 1, p. 868, listed seven of Garrett’s Armenian manuscripts, and this numbering was followed decades later in a far more authoritative catalogue: Avidis Krikor Sanjian, A Catalogue of Medieval Armenian Manuscripts in the United States (1976), pp. 392-417. At the same time, Princeton was using different sequences of manuscript numbers for Garrett’s Armenian manuscripts, which were shelved them next to Princeton Armenian Manuscripts. This led to confusion about the numbering of Princeton’s Armenian manuscripts because of their inclusion in two published surveys. In the interest of clarity, what De Ricci had designated nos. 17-23 (among western manuscripts) became Garrett Armenian, nos. 1–7; followed by Garrett Armenian Manuscripts, nos. 8-14, which Sanjian had designated Armenian Supplementary Series because they were not in DeRicci. In 1993, two other Armenian manuscripts were discovered in the Garrett Collection and assigned Garrett Armenian numbers. The list below provides old and new manuscript numbers, which will also be indicated in Voyager bibliographic records.

Three other Armenian manuscripts are in the Princeton Collection of Armenian Manuscripts and two in The Scheide Library. These are also described in Sanjian, pp. 418-32. Princeton Armenian, no. 2, accessioned by the Princeton University Library in 1951, has an interesting Garrett family connection. The Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople gave this manuscript to Cleveland H. Dodge (1860-1926), Class of 1879, in New York, on 3 January 1919, in recognition of his humanitarian and philanthropic work for the Armenian people during World War I. The manuscript passed by descent to his twin sons, Cleveland E. Dodge and Bayard Dodge, both members of the Class of 1909. Bayard Dodge’s daughter Margaret married Johnson Garrett, one of Robert Garrett’s sons, in 1936. In addition to the excellent descriptions in Sanjian, a number of the manuscripts have been described in an Armenian journal Sion (July-August 1971), vol. 45, pp. 265-70; and exhibited at the Pierpont Morgan Library and described in Treasures in Heaven: Armenian Illuminated Manuscripts, edited by Thomas F. Mathews and Roger S. Wieck (1994). For additional information, contact Don C. Skemer, Curator of Manuscripts, dcskemer@princeton.edu

CHECKLIST

● Garrett Armenian MSS., no. 1. Gospel Book, Late 17th century. Formerly Garrett MS. 17.

● Garrett Armenian MSS., no. 2. Gospel Book, 1449. Formerly Garrett MS. 18.

● Garrett Armenian MSS., no. 3. Psalter and Breviary, 16th century. Formerly Garrett MS. 19.

● Garrett Armenian MSS., no. 4. Breviary, 17th century. Formerly Garrett MS. 20.

● Garrett Armenian MSS., no. 5. Hymnal, 17th century. Formerly Garrett MS. 21.

● Garrett Armenian MSS., no. 6. Psalter, 16th century. Formerly Garrett MS. 22.

● Garrett Armenian MSS., no. 7. Alexander Romance (6 illuminated leaves), 1526. Formerly Garrett MS. 23.

● Garrett Armenian MSS., no. 8. Discourses by St. Gregory the Illuminator, 10th-11th century. Formerly Supplementary Series, no. 1.

● Garrett Armenian MSS., no. 9. Gospel Book, 11th century. Formerly Supplementary Series, no. 2.

● Garrett Armenian MSS., no. 10. Astronomical text, 1774-75. Formerly Supplementary Series, no. 3.

● Garrett Armenian MSS., no. 11. Amulet Roll (Phylactery) with 11 miniatures, 18th century. Formerly Supplementary Series, no. 4.

● Garrett Armenian MSS., no. 12. Armenian Gospel miniature, 1311. Formerly Supplementary Series, no. 5 (missing since 1980).

● Garrett Armenian MSS., no. 13. Gospel Book, 16th century? Found in 1993 among Garrett Islamic MSS, Enno Littmann series.

● Garrett Armenian MSS., no. 14. Uncataloged. Found in 1993 among Garrett Islamic MSS, Enno Littmann series.

● Princeton Armenian MSS., no. 1. Menologion, 1683 (2 leaves).

● Princeton Armenian MSS., no. 2. Gospel Book, 1730.

● Princeton Armenian MSS, no. 3. Uncataloged.

●Scheide 84.16. Gospel Book, 1239. Formerly Scheide M74.

●Scheide 83.11. Gospel Book, 1625-33. Formerly Scheide M80.

Garrett Armenian MSS., no. 2, fols. 16v-17r.

Gift of Robert Garrett, Class of 1897.

You must be logged in to post a comment.