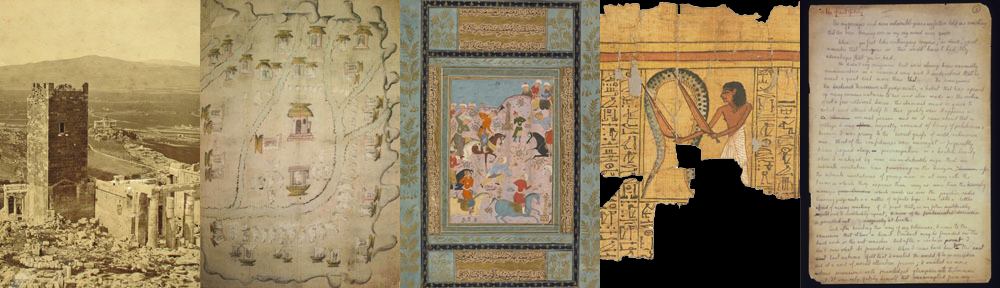

Two of Princeton’s illuminated Byzantine manuscripts of the Gospels have been on view in an exhibition, Jerusalem 1000–1400: Every People Under Heaven, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in New York, from 26 September 2016 until 8 January 2017. The two manuscripts are among over 200 works of art from some 60 lenders worldwide, including the Vatican Library and Bodleian Library. From the Manuscripts Division is Garrett MS. 3, Gospels, 12th century, gift of Robert Garrett, Class of 1897; and from the Scheide Library is Scheide M70, Gospels, 11th century, bequest of William H. Scheide, Class of 1936. The manuscripts were formerly in Greek Orthodox religious institutions in the Jerusalem area. Garrett MS. 3 was written in the Monastery of St. Sabas (Mar Saba), located in the Judean desert, east of Jerusalem, in 1135/36, according to a scribal note; and Scheide M70 was in the library of the Anastasis Church and later the Monastery of Abraham, both in Jerusalem, at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. For descriptions of these and other Byzantine and post-Byzantine manuscripts in the Library, see Greek Manuscripts at Princeton, Sixth-Nineteenth Century: A Descriptive Catalogue, by Sofia Kotzabassi and Nancy Patterson Ševčenko, with the collaboration of Don C. Skemer (Princeton: Department of Art and Archeology and the Program in Hellenic Studies, in association with Princeton University Press, 2010). The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s exhibition focuses on the important role played by art in the spiritual lives of multiple faiths and cultural traditions that coexisted in the Holy City between 1000 and 1400. Nearly a quarter of the objects will come from Jerusalem itself, including loans from its religious communities. Almost a third of the items in the exhibition are manuscripts, including examples in Greek, Hebrew, Georgian, Armenian, and Arabic. Metropolitan Museum of Art curators Barbara Drake Boehm and Melanie Holcomb curated the exhibition and prepared the published catalogue.

Author Archives: Don Skemer

Revolutionary Times at Prospect Farm

History remembers Colonel George Morgan (1743-1810), a Philadelphia native and merchant, as an officer in the Continental Army, an American agent for Indian Affairs, and a speculator in Western lands. In his 1932 biography of George Morgan, the historian Max Savelle emphasized Morgan’s role as a “distinguished citizen” of America, which had to secure political and economic independence, tame the frontier, and forge effective relations with indigenous peoples. In 1779, Morgan organized George Washington’s meeting with Lenape (Delaware) Indian chiefs, and he also assumed responsibility for the education of three Lenape boys in Princeton. Morgan even became an honorary member of the Lenape. Also in 1779, he bought more than two hundred acres of land in Princeton, including the land now occupied by Prospect House and Prospect Gardens, and there he built a multi-storey stone farmhouse for himself and his family. Views of the farmhouse survive. Prospect Farm was a short distance southeast of the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University), which was then largely a residential college confined to Nassau Hall, with the President’s office, classrooms, dorm rooms, dining facilities, and the library. When John Witherspoon became President in 1768, his duties went far beyond administration. He preached sermons and taught moral philosophy, history, and other subjects.

Revolutionary times posed special problems for the town of Princeton and its leading citizens, beginning with the Battles of Trenton and Princeton. Morgan recorded in his journal (1762-1806), which is in the Manuscripts Division’s George Morgan Collection (C1394), that he planted rows of cherry trees, in part to replace those cut down by occupying British soldiers for firewood in the winter of 1776. In April 1780, he wrote a memorandum in his journal about planting rows of cherry trees along roads leading to his house, in part to remedy damage, and noted, “The British Army in December 1777 burned & destroyed all the Houses of the Farm & most of the Apple Trees for Firewood.” The cherry trees were also for the pleasure of Princeton undergraduates. At Prospect Farm, Morgan could be a gentleman farmer specializing in scientific farming and agricultural experiments, such as growing different varieties of corn. Bee culture and insect control were other interests. Morgan also rebuilt houses on his land as well.

The George Morgan Collection includes several letters that he wrote to Brigadier General Lewis Morris (1726-98), a fellow landowner and developer. Originally from Morrisania, New York, Morris was a Signer of the Declaration of Independence and a delegate to the Continental Congress. At the time the letter was written, Morris was living in Rocky Hill, near Princeton. Morgan opens an undated letter with an expression of his joy “on the late happy Events.” This probably refers to the recent surrender of the British army under Lord Charles Cornwallis at the Battle of Yorktown (19 October 1781), after being defeated by Continental forces under George Washington and French forces under the Comte de Rochambeau. George Morgan asks Lewis Morris to a celebratory dinner and ball at Prospect Farm. In addition, Morris was to extend the invitation to a group of people on his side of the “Mountain,” a word no doubt referring to Ten Mile Run Mountain (geologically part of the Rocky Hill Ridge), east of the Millstone River. “We have fixed on Saturday,” Morgan wrote, “that we may not interfere with Trenton, where they have a Dinner & Ball on Monday. I expect the Cards from thence for your family, some time today. I have dispatched Beekman for the best Casks of Wine & Claret he can find in the City and have wrote to Mr. Shippen to come up with all his Musick, so that I hope your principal Trouble will be in your seat as President. All the Ladies, married and single, propose to wear an union Rose in their Breasts.”

On the verso of the letter is a “List of the Gentlemen & Ladies over & on the Mountain to be invited to a Dinner & Ball.” The invitees clustered in the area of Rocky Hill, in Somerset County, less than five miles northeast of Prospect Farm and Nassau Hall. The names of the grandees on the invitation list (see below) must be reconstructed because it omits first names and has alternative spellings for several surnames. Invitees appear to include Major John Berrien (1759-1815) and General Stephen Heard (1740-1815), with their wives and children. “Mrs. Berrian” was probably Margaret Berrien, mother of Major Berrien and widow of Justice John Berrien (1711-72), whose Rockingham home served as George Washington’s final headquarters during the American Revolution. Washington stayed there from August to November 1783, while Congress was meeting at Nassau Hall, and it was at Rockingham that Washington wrote his farewell address to the Continental Army. “Col. Vandike” was most likely Henry Van Dyke, a militia officer from Somerset County. “Mr. Rutherford” may have been John Rutherfurd (1760-1840), Princeton Class of 1776. Rutherfurd was a nephew of William Alexander, Lord Stirling (1726-83), a Brigadier General in the Continental Army; Rutherfurd later married Helena Magdalena Morris (1762–1840), daughter of Lewis Morris. Also invited were unidentified members of the Mercer, Lawrence, and Van Horne families. However the dinner and ball turned out, this was hardly George Morgan’s last chance to invite prominent people to Prospect Farm. On June 25, 1783, Morgan wrote to Elias Boudinot (1740-1821), President of Congress, to invite members of the Continental Congress, then assembled at Nassau Hall, to be his guests at Prospect Farm.

For more information about New Jerseyana holdings of the Manuscripts Division, see the recent blog-post, or contact Public Services, at rbsc@princeton.edu

George Morgan’s invitation list

Commonplace Books and Uncommon Readers

From the Renaissance to the nineteenth century, educated people often used what we call “commonplace books” to store and retrieve bits of text and other information, chiefly gleaned from printed books. European readers filled blank paper notebooks with information organized under specific headings to facilitate later retrieval and use. While the word commonplace (from the Latin term locus communis) suggests learned themes or arguments, these notebooks could be used for information of any sort, from theology and natural philosophy, to popular songs and recipes, brief quotations and extracts, and practical information for working professional physicians and lawyers. Over the centuries, commonplace books became so ubiquitous in the western world that more than two hundred such volumes survive just in the Princeton University Library’s Manuscripts Division. They are of research interest not only for the information they contain, but also because of how that information was gathered, the variety of sources, and what the contents may tell us about the life and reception of particular authors, books, and ideas. Commonplace books are perhaps most fascinating and revealing when they act as a window into the minds, social milieu, and intellectual circles of people, whether famous or obscure, who kept and used them so long ago. We can see this vividly with the Manuscript Division’s most most recent acquisition, a commonplace book of medicine and secrets.

Bernardino Ciarpaglini (b. 1655), an Italian physician and experimental anatomist, kept this volume in Tuscany from around 1680 to 1730. His ownership is attested by an inscription written on the turn-in of the upper cover, which records his birth date and hour, as well as that of his brother Belisario. Ciarpaglini copied most of the entries in 23 alphabetical sections, within a blank stationer’s volume, using heavy laid paper with a tre lune watermark, especially popular with Venetian papermakers at the time. The text block was modified with a thumb index cut along the fore edge (see illustration below). Ciarpaglini was born in Pratovecchio and practiced medicine there until he relocated to Cortona, some 75 kilometers to the southeast. There he spent the rest of his professional life and even served for a while as one of the priori of the Communal Council of Cortona, 1716–22. To judge from the contents of the commonplace book, Ciarpaglini was something of a general practitioner, interested in everything from gout to plague. Ailments of women and children were part of his practice. At the same time, he developed a strong professional reputation, which was no small achievement at a time when physicians had to compete with charlatans and healers.

Ciarpaglini is mentioned positively in contemporary medical and scientific literature for his expertise on epilepsy, concerning which there is extended discussion in the commonplace book; fistulas of the tear ducts; and other disorders. While still living in Pratovecchio around 1679, Ciarpaglini conducted anatomical experiments, unfortunately on live dogs, to remove an entire spleen and a portion of the liver. In 1680, he was among the distinguished physicians who observed the Italian anatomist Giuseppe Zambeccari (1655–1728) performing an excision of a dog’s spleen. In 1723, he provided autobiographical information before giving expert testimony to the Sagra Congregatione de’ Riti about the state of the sacred body of St. Margaret of Cortona (canonized in 1728), including the condition of her head, face, eyes, mouth, arms, hands, and feet. His appearance as an expert witness was ancillary to the Church practice since the second half of the thirteenth century to call on respected physicians to testify in canonization processes in order to establish that miraculous cures had no natural explanation. Concerning such cases, see Joseph Ziegler, “Practitioners and Saints: Medical Men in Canonization Processes in the Thirteenth to Fifteenth Centuries,” Social History of Medicine, vol. 12, no. 2 (1999), pp. 191-225.

Our physician wrote his entries in Italian, always in a rapid but clear cursive hand. Some of the content was copied from published books, such as the reference on the turn-in of the back cover, mentioning Albertus Magnus (d. 1280), Liber mineralium (“Libro de minerali”). Many entries are credited to particular physicians and clerics in Tuscany, probably by oral transmission. There are recipes of every type, many of which are preceded by the Latin abbreviation Rx, indicating a medical prescription. There are preparations for a wide array of conditions and circumstances, such as to induce vomiting, help one fall asleep, clean teeth, facilitate childbirth, and suppress lactation. Particular remedies include a Chinese elixir said to have been used by King Louis XIV; an aphrodisiac ointment made from crushed ants; and a cure for sexual dysfunction, prepared from chocolate, orchids, champagne, and other ingredients. A few recipes were crossed out with critical notes saying that they were ineffective. Some recipes identify their source and note where and when they were transcribed. Secrets include alchemical transmutation of lead into silver, production of a liquid that would turn a person’s face black, removing stains, cleaning gold objects, fishing effortlessly, preparing tobacco, preserving wine, and making a woman tell the truth in her sleep. There is a five-page section on cryptology, accompanied by an separate cipher table and key written on a small piece of parchment, probably for use while traveling. Ciarpaglini notes that he had learned the cipher from Giuseppe da Contignano, a local Capuchin friar. There is also a loose paper copy of a 1599 recipe for wine vinegar, attributed to a certain Giacomo Buonaparte.

To identify relevant holdings in the Manuscripts Division, one should search for “Commonplace Books” (as a subject heading) in the online catalog, where bibliographic records are found by country and century; and in the finding aids site. One can also do a Subject Browse search in Blacklight. Please contact Public Services for other information, at rbsc@princeton.edu

Scott and Zelda Document Their Lives

The Manuscripts Division is pleased to announce that the scrapbooks of F. Scott Fitzgerald (Class of 1917) and Zelda Fitzgerald are now online in the Princeton University Digital Library (PUDL). The Fitzgeralds’ daughter Scottie gave the scrapbooks to the Princeton University Library in the decades following the donation of most of the Fitzgerald Papers in 1950. F. Scott Fitzgerald saw life as raw material for literature. His gift for autobiographical observation and self-documentation can be seen in the way he kept his papers and scrapbooks. He chronicled his early life in “A Scrap Book Record, compiled from many sources of interest to and concerning one F. Scott Fitzgerald,” as he wrote boldly in white ink to label the volume. He traces his life from birth through Princeton and service in the U.S. Army during World War I, concluding with the acceptance of his short story Head and Shoulders for publication in The Saturday Evening Post (1920). Fitzgerald was perhaps inspired to keep scrapbooks by his mother, Mary “Mollie” McQuillan Fitzgerald, who chronicled his formative years until 1915 in The Baby’s Biography, by A. O. Kaplan, with Pictures by Frances Brundage (New York: Brentano’s, © 1891). Between 1920 and 1936, Fitzgerald compiled five other scrapbooks, in which he usually emphasized his published books and short stories, sometimes adding unrelated materials about his life, travels, and friends. Zelda Fitzgerald kept a scrapbook of her own until 1926, chiefly relating to her family and childhood in Montgomery, Alabama; and early married life with Scott and Scottie.

Scrapbook contents include newspaper clippings, book reviews, and interviews relating to F. Scott Fitzgerald’s life and writing; tearsheets of magazine articles and short stories; dust covers and promotional announcements for books and collections; printed ephemera; formal studio portraits of the author, photographs of friends and acquaintances, and family photos (mostly small snapshoots) of the Fitzgeralds (Scott, Zelda, Scottie); memorabilia; and occasional documents and letters from authors, publishers, and friends. Many of the photographs and clippings are well known and have been often reproduced. But there are a few surprising items as well, such as F. Scott Fitzgerald’s check-stub book for the First National Bank of Princeton, October-November 1916, while he was a Princeton undergraduate; his grimacing self-portrait in a Photomaton coin-coperated photo booth, probably at a train station in the late 1920s; and his personal copy of the Directory of Directors, Writers etc. (1931), proudly kept because it includes his name in the company of Hollywood directors and writers. When Fitzgerald moved from Baltimore to North Carolina in 1936, he put the scrapbooks in storage, and though he later had them shipped to him in Hollywood, the author never again added to them.

The best resource for understanding the scrapbook contents, usually unidentified and undated, is Matthew J. Bruccoli, Scottie Fitzgerald Smith, and Joan P. Kerr, eds., The Romantic Egoists: A Pictorial Autobiography from the Scrapbooks and Albums of F. Scott Fitzgerald and Zelda Fitzgerald (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1974). This is because much of the contents was reproduced with commentary in The Romantic Egoists. Scottie Fitzgerald Lanahan noted (p. ix), “ninety percent of the illustrations in this book…was taken from the seven scrapbooks and five photograph albums….” Physical access to the original scrapbooks is restricted for compelling preservation reasons because all but The Baby’s Biography are largely made up of highly acidic newsprint pasted down on equally acidic album paper. The scrapbooks were digitized in 1999 as part of the Library’s Fitzgerald Papers preservation project, funded by the Save America’s Treasures, a grant initiative administered by the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). Over the past fifteen years, researchers have been able to consult the digitized scrapbooks in the Department of Rare Books and Special Collections. The inclusion of the Fitzgerald scrapbooks in the PUDL will now enable everyone to see and appreciate them, along with the manuscripts of This Side of Paradise (1920) and The Great Gatsby (1925). These materials and more can be found in the Fitzgerald Collection.

The online version of the scrapbooks has been digitally watermarked and provides information about “Usage Rights,” including form of citation, reproduction, copyright, and other issues. For information about reproducing selective images in the scrapbooks, please contact Public Services, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections. rbsc@princeton.edu

First page of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s

Scrapbook I, showing dust cover of

This Side of Paradise (1920)

and snapshots of Zelda.

Archival Research on African American Literature and Authors

The Manuscripts Division’s most important archival holdings for African American literature are the Toni Morrison Papers (C01491), the major portion of which are now open for research. But there are other relevant archival collections, chiefly in the archives of American publishing houses and literary magazines, and of American and British literary agenices. The most substantial for research are the author files for Richard Wright (1908-60), dating from 1938 to 1957, found in Selected Records of Harper & Brothers (C0103). These files include editorial and business correspondence with Wright, his agent Paul R. Reynolds, the publishing house’s editors, and promotional staff; reader’s reports; and review media relating to books published over several decades: Uncle Tom’s Children (1938), Native Son (1940), Black Boy (1945), The Outsider (1953), Black Power (1954), and Pagan Spain (1957), as well as books for which Wright supplied introductions. The Harper & Brothers files are complemented by the Wright files of the British literary agency Victor Gollancz Ltd. (C1467), which include correspondence, contracts, and readers’ reports for Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Native Son, Black Boy, and American Hunger (1978). There are also Wright letters and photographs of 1946-49 in the Sylvia Beach Papers (C0108), as well as Wright’s novella The Man Who Lived Underground; and letters of 1945-56 in the author files of Story Magazine and Story Press (C0104).

Several other Harlem Renaissance authors are represented in holdings. For Langston Hughes (1902-67), the Manuscripts Division has occasional letters and photos in the Sylvia Beach Papers and Carl Van Doren Papers (C0072), and in the New Review Correspondence of Samuel Parker (C0111), the Archives of Charles Scribner’s Sons (C0101), and the Archives of the John Day Company (C0123). Posthumous files (1968-72) pertaining to his books are found in the Archives of Harold Ober Associates (C0129), through their British affiliate Hughes Massie Ltd. Additional items are in the Franklin Books Program archives at Mudd Library. The Archives of Charles Scribner’s Sons has author files for Zora Neale Hurston (1891-1960), including 100-plus items, 1947-63, of which 25 are letters by Hurston, mostly pertaining to her novel Seraph on the Suwanee (1948). Some additional Hurston material is found in the Story archives. For the African American poet and editor Kathleen Tankersley Young (1903-33), the Manuscripts Division has correspondence with New York book designer and printer Lew Ney and his wife Ruth Widen, 1928-32 (C1273). Young was editor of Modern Editions Press and Blues: A Magazine of New Rythms during the Harlem Renaissance.

The Manuscripts Division has a folder of letters (1901-5) from the poet Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872-1906) to Harrison Smith Morris, editor of Lippincott’s Magazine, in the Harrison Smith Morris Papers (C0003); as well as correspondence of the African American historian Carter G. Woodson (1875-1950), with fellow historian Charles H. Wesley, 1925-50 (C1310). Woodson was the founder of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History and in his writing called attention to W.E.B. Dubois and the Harlem Renaissance. Also in the Manuscripts Division are the correspondence files of the New York Urban League, 1922-79 (C0869). Three letters of 1905-6 about W.E.B DuBois’s Souls of Black Folk are found in correspondence between the Chicago publisher A. C. McClurg & Company and the London literary agent Charles Francis Cazenove (C1553). Also of interest is a small collection of papers of George Padmore (1903-59), a journalist born in Trinidad, including correspondence with Henry Lee Moon (1901-85), editor of the Amsterdam News (C1247).

Ralph Ellison (1914-1994) and Gwendolyn Brooks (1917-2000) are the best-documented African American authors of the post-war generation in the Manuscripts Division. Ellison materials are primarily found in the archives of the Quarterly Review of Literature [QRL] (C0862). This literary magazine was edited from 1943 to the 1990s by the American poet Ted Weiss, who taught at Princeton, 1967-87. QRL‘s issue files include correspondence with Ralph Ellison, as well as corrected typescripts, and proofs of his second, posthumously published novel Juneteenth. Includes the following. (1) “The Roof, the Steeple and the People,” QRL, vol. 10, no. 3 (1959-60), relating to the nicoleodeon excursion. There are also proofs in box 6, folder 2, and a corrected typescript in box 6, folder 3; (2) “Juneteenth,” QRL, vol. 13, no 3-4 (1965), in box 8, folder 4; (3) “Night-Talk,” QRL, vol. 16 (1972), a movie-going episode in Atlanta, with an edited revision, box 11, folder 4. There are a few Ellison letters in the archives of The Hudson Review and in the recently acquired papers of Joseph Frank (1918-2013), Professor of Comparative Literature, who received a 3-page letter from Ellison in 1964, in which he explains the obscurity of the “pink hospital scene” in his novel Invisible Man by describing how he cut out a 225-page section from the middle of book. Gwendolyn Brooks is documented by 14 folders for the years 1944-58 in the Selected Records of Harper & Brothers (C0103), as well as additional materials in other collections. Recently, the Manuscripts Division acquired a sound recording and transcription of an interview that Playboy Magazine‘s articles editor James Goode conducted with James Baldwin (1924-87) in 1967 and Alex Haley (1921-92) edited and shortened for publication the following year (C1557).

Beyond African American authors, the Manuscripts Division holds some literary collections relating to the Afro-Carribean experiences. The best example is in the papers of the contemporary American author Madison Smartt Bell (C0771), Princeton Class of 1979, including manuscripts, corrected typescripts, and proofs for his trilogy about Toussaint Louverture and other leaders of the Haitian Revolution. The first novel was All Souls Rising (1995), which was a finalist for the 1995 National Book Award and the 1996 PEN Faulkner Award, and won the 1996 Anisfield-Wolf Award for the best book of the year. The novel was continued in Master of the Crossroads (2002) and The Stone Builder Refused (2004). Providing context for Bell’s writing is his correspondence with his publishers, agents, and friends. The Manuscripts Division also holds the correspondence of Professor Léon-François Hoffmann with the Haitian poet René Depestre, 1984-2003 (C1103).

Archival, printed, and audiovisual materials about African American literature and history can be found in the various divisions and collections of the Department of Rare Books and Special Collections. For general information about holdings, please contact Public Services, at rbsc@princeton.edu

Toni Morrison Papers Open for Research

The Princeton University Library is pleased to announce that the major portion of the Toni Morrison Papers (C1491), part of the Library’s permanent collections since 2014, is now open for research. The papers are located in the Manuscripts Division, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, in the Harvey S. Firestone Memorial Library. They contain more than two hundred linear feet of archival materials that document the life and work of Toni Morrison, Nobel Laureate in Literature (1993) and Robert F. Goheen Professor in the Humanities (Emeritus) at Princeton University. Morrison’s papers were gathered from multiple locations over more than two decades, beginning with the files recovered by the Library’s Preservation Office after the tragic fire that destroyed her home in 1993. Over the past eighteen months, the most significant of the papers have been organized, described, cataloged, and selectively digitized. The papers are described online in a finding aid.

Most important for campus-based and visiting researchers are some fifty linear feet of the author’s manuscripts, drafts, and proofs for the author’s novels The Bluest Eye (1970), Sula (1973), Tar Baby (1981), Beloved (1987), Jazz (1992), Paradise (1997), Love (2003), A Mercy (2008), Home (2012), and God Help the Child (2015). The only exception are materials for Song of Solomon (1977), which are believed lost. In the interest of preservation, by agreement with the author, all of these manuscripts have been digitized in the Library’s Digital Studio. Research access to digital images of Morrison’s manuscripts will be provided in the Rare Books and Special Collections Reading Room. The study of Morrison’s manuscripts illustrates her approach to the craft of writing and help trace the evolution of particular works, from early ideas and preliminary research, to handwritten drafts on legal-size yellow notepads, and finally corrected typescripts and proofs. The early drafts often differ substantially from the published book in wording and organization, and contain deleted passages and sections.

A single yellow notepad may contain a variety of materials, including content related to other works, drafts of letters, inserts for later typed and printed versions, and other unrelated notes. Corrected typescript and printout drafts often show significant revisions. Material from various stages of the publication process is present, including setting copies with copy-editor’s and typesetter’s marks, galleys, page proofs, folded-and-gathered pages (not yet bound), blueline proofs (“confirmation blues”), advance review copies (bound uncorrected proofs), and production/design material with page and dust-jacket samples. In addition to documenting Morrison’s working methods, the papers make it possible to see how books were marketed to the reading public and media, and also to trace the post-publication life of books, as they were translated, repackaged, reprinted, released as talking books, and adapted for film.

Among unexpected discoveries that came to light during archival processing are partial early manuscript drafts for The Bluest Eye and Beloved; and born-digital files on floppy disks, written using old word-processing software, including drafts of Beloved, previously thought to have been lost. Morrison also retained manuscripts and proofs for her plays Dreaming Emmett (1985) and Desdemona (2011); children’s books, in collaboration with her son Slade Morrison; short fiction; speeches, song lyrics; her opera libretto for Margaret Garner, with music by the American composer Richard Danielpour; lectures; and non-fiction writing.

Also valuable for researchers is Morrison’s literary and professional correspondence, approximately fifteen linear feet of material, including letters from Maya Angelou, Houston Baker, Toni Cade Bambara, Amiri Baraka, Gwendolyn Brooks, Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee, Leon Higginbotham, Randall Kennedy, Ishmael Reed, Alice Walker, and others. Additional literary correspondence is found in Morrison’s selected Random House editorial files, where her authors included James Baldwin, Toni Cade Bambara, Angela Davis, and Julius Lester. Morrison also retained drafts, proofs and publication files related to two works by Toni Cade Bambara, which Morrison posthumously edited for publication; as well as photocopies of selected correspondence of James Baldwin, 1957-1986, and materials relating to Baldwin’s literary estate.

The remaining Morrison Papers are being processed and will be made available for research gradually over the next year, with arrangement and description to be completed by spring 2017. These include her Princeton office files and teaching materials, fan mail, appointment books (sometimes called diaries), photographs, media, juvenilia, memorabilia, and press clippings. Complementing the papers are printed editions of Morrison’s novels and other published books; translations of her works into more than twenty foreign languages; and a selection of annotated books. Morrison’s additional manuscripts and papers will be added over time.

Beyond the Toni Morrison Papers, the Department of Rare Books and Special Collections holds other archival, printed, and visual materials about African American literature and history. The best files are in American publishing archives. For example, the Manuscripts Division holds the Harper & Brothers author files for Richard Wright’s books Uncle Tom’s Children (1938), Native Son (1940), Black Boy (1945), Outsider (1953), Black Power (1954), and Pagan Spain (1957); Charles Scribner’s Sons author files for Zora Neale Hurston, chiefly pertaining to her novel Seraph on the Suwanee (1948); and the Quarterly Review of Literature files of Ralph Ellison’s corrected typescripts and proofs for three extracts from early working drafts of his second, posthumously published novel Juneteenth (1999).

For information about the Toni Morrison Papers, please consult the online finding aid. For information about visiting the Department of Rare Books and Special Collections and using its holdings, please contact the Public Services staff at rbsc@princeton.edu

Beloved early draft

Toni Morrison Papers (C1491)

Princeton University Library

Rediscovering Lost Mayan Text

Researchers regularly make discoveries in the reading rooms of the Department of Rare Books and Special Collections. Curators, catalogers, and conservators can make their own discoveries when describing and preparing materials for research use. A case in point is the recent recovery of Mayan textual fragments during conservation treatment of an eighteenth-century Latin American manuscript in the Garrett-Gates Collection of Mesoamerican Manuscripts (C0744.01, no. 177), gift of Robert Garrett (1875-1961), Class of 1897. It was written in 1759 by a scribe named Tomás Ossorio, at San Sebastián Lemoa, Guatemala, and is one of nearly 300 Mesoamerican manuscripts, documents, and related items in the Manuscripts Division, each written in whole or part in one of the indigenous languages of the Americas. Garrett acquired most of his Mesoamerican manuscripts from the collection of William Gates (1863-1940).

This Mesoamerican manuscript contains a single text: Domingo de Vico (1485-1555), Teologia indorum, translated from Latin into K’iche’ (or Quiché), a Mayan language spoken by the people of central Guatemala. It was written in the Roman alphabet and disseminated by scribal copying during the Contact Period. Vico was a Dominican friar, who left his native Spain for the Kingdom of New Spain. He prepared this treatise in Chiapas, Mexico, for the use of Dominicans at the parish level to interact with the indigenous populations and their ancestral religious beliefs, which Spanish conquerors and missionaries viewed as a form of “idolatry.” The Teologia indorum is filled with brief Christian lessons drawn from the New Testament and lives of the saints, with explanations of basic Christian concepts. Vico’s text was translated by native speakers into the Mesoamerican languages of K’iche’, Kaqchikel, and Tzutuhil between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries. The present manuscript includes pen-and-ink drawings, perhaps the work of the scribe himself, depicting the Cross with the Virgin Mary and St. John (fol. 1 v); and the Virgin Mary and Christ Child (fol. 113v). In total, there are at least a dozen extant manuscripts of Vico’s text in translation, of which Princeton has seven (C0744.01, nos. 175-180, 227) and the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (Paris) has five.

When the manuscript arrived in the Library in 1949, it was in a crudely made, repeatedly repaired one-piece animal-hide cover or wrapper, not a contemporary binding. The binding was dysfunctional and was damaging the fragile paper leaves. Whoever was responsible for this later binding had ignored original folio numbers and bound the manuscript out of order. Moreover, one could see portions of five leaves of unrelated contemporary K’iche’ text, written in different hands. These leaves were upside down relative to the Vico text and lined the inside of the animal-hide cover that wrapped around the text block The lining was possibly an attempt to stiffen the wrapper. Mick LeTourneaux, Book Conservator in the Library’s Preservation Office, disbound the manuscript, cleaned and mended the text leaves, reassembled them in the correct order, and rebound the manuscript in a conservation binding employing long-stitch sewing for flexibility. LeTourneaux was able to recover the unrelated text leaves from inside the cover. These leaves were then separated, mended, encapsulated, and rehoused in a custom drop-spine box, along with the rebound manuscript and animal-hide cover.

Don C. Skemer, Curator of Manuscripts, sent digital images of the recovered leaves to Matthew Restall, Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of Latin American History and Anthropology, and Director of Latin American Studies, at Pennsylvania State University. Restall has been a frequent research visitor to the Department of Rare Books and Special Collections. He reads several Mayan languages and does research on the ethnohistory of the Yucatan and Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize. Scott Cave and Megan McDonie, two of Restall’s graduate students, studied the digital images and were able to identify three folios of prayers and other liturgical text, written in K’iche’ with some crossover into Kaqchikel. Like most Mesoamerican religious texts of this era, the text incorporates Christian sacred names and other loan words in Spanish and Latin. The remaining two folios are in K’iche’ and may deal with church business. The texts did not precisely match any known texts and will require more study.

The Manuscripts Division has been working with the Preservation Office for years to conserve scores of Mesoamerican manuscripts that came to the Library in poor condition nearly seventy years ago. Several of the manuscripts have also been digitized in the Library’s Digital Studio and added to “Treasures of the Manuscripts Division,” in the Princeton University Digital Library (PUDL). For more information about the collection, contact Public Services, at rbsc@princeton.edu

Aubrey Beardsley: A British Artist for the 1890s

The Manuscripts Division has particularly rich holdings on Aubrey Beardsley (1872-98), the celebrated fin-de-siècle artist, who is best known for his exquisite black-and-white book illustrations. Beardsley’s books, posters, bookplates, and magazine contributions—most notably Oscar Wilde’s Salome and The Yellow Book—brought him international celebrity before his untimely death from tuberculosis at age 25. Through his art, Beardsley became the leading exponent of a British movement referred to by its detractors as “decadent,” as was Wilde in literature. He completed nearly 1100 drawings in just six years. Beardsley absorbed the Pre-Raphaelites, the Aesthetic movement, Japanese woodblock prints, Greek vases, and eighteenth-century engravings to produce the bold, instantly recognizable “Beardsley style.” Then as now, Beardsley’s artistic vision can be seen as as amusing, grotesque, decadent, perverse, liberating, erotic, or even obscene. But it is always original, unique, and arresting.

Yet while Beardsley’s art has been much admired since his own time, the daunting task of identifying and locating all of his illustrations would have to wait more than a century after his death. The scholarly world is fortunate that a comprehensive catalogue has finally been published. Professor Linda G. Zatlin, Department of English, Morehouse College, spent three decades preparing a Beardsley catalogue raisonné, including innumerable research trips and photography orders to the Department of Rare Books and Special Collections. Zatlin has carefully identified, described, studied, and reproduced nearly 1100 extant Beardsley illustrations, whether they survive only in printed editions or also in drawings and sketches preserved in libraries and museums worldwide. The result is an indispensable catalogue, both handsome and learned, which will long remain the standard guide to Beardsley’s work.

Linda G. Zatlin, Aubrey Beardsley: A Catalogue Raisonné (New Haven: Yale University Press for the The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2016), a two-volume boxed set, with 75 color and 1145 black-and-white illustrations. Available from Yale University Press, the catalogue provides a full record for each work, with a provenance note and exhibition history; and discusses themes, motifs, symbolism, and critical reception, with an up-to-date bibliography. Among those to whom the catalogue is dedicated is Mark Samuels Lasner, who co-curated the Library’s Beardsley centennial exhibition (1998-99) with Don C. Skemer, Curator of Manuscripts.

More than 100 of the original Beardsley drawings and sketches cataloged and reproduced by Zatlin are in the Manuscript’s Division’s Aubrey Beardsley Collection (C0056). Most of these were donated to Princeton in 1948 by the American artist and art collector A. E [Alfred Eugene] Gallatin (1881-1952). The collection was one of the earliest exhibitions in Firestone Library, curated by Alexander D. Wainwright, Class of 1939. Additions have been made to this collection in the decades since the Gallatin gift. The drawings and sketches were done for book illustrations, borders, chapter headings, title pages, and posters, and book plates.

These are complemented by selected correspondence and manuscripts. Among Beardsley’s major correspondents are Edmund Gosse, Robert Underwood Johnson, and Leonard Smithers. In addition, there is correspondence from Douglas Ainslie, Joseph M. Dent, John Lane, and Beardsley’s mother and sister, as well as photographs of Beardsley and family members. His own literary manuscripts include “The Art of Hoarding,” “Under the Hill,” and “The Ivory Piece.” The Department of Rare Books and Special Collections also has printed editions of all works illustrated by Beardsley.

For information about Beardsley holdings in the Manuscripts Division, including several recent acquisitions, please contact Don C. Skemer, Curator of Manuscripts, dcskemer@princeton.edu

The Criminal Adventures of Jack Sheppard

The latest additions to the Morris L. Parrish Collection of Victorian Novelists (C0171) include two volumes of manuscripts by William H. Ainsworth (1805-82), chiefly for his novel Jack Sheppard: A Romance. This lurid Newgate School novel was serialized in Bentley’s Miscellany (1839-40) and published by Richard Bentley (1839) as a “triple-decker” (3-volume novel). The novel was published with a series of 27 etchings by the eminent British illustrator George Cruikshank, a large collection of whose papers (C0256) is also in the Manuscripts Division. The novel’s protagonist is Jack Sheppard (1702-23), a London apprentice carpenter, who turned to a life of crime and in the course of just two years achieved notoriety as a housebreaker, pick-pocket, and outlaw, until he was executed at the Tyburn gallows. Sheppard’s audacious prison escapes made him an appealing “low-society” anti-hero for the novel, which became a bestseller and outsold Oliver Twist, also published around that time. Yet the novel’s popularity displeased many critics, who considered it unseemly for the publisher and author to profit from a sensationalized life of an unrepentant criminal.

A contemporary of Charles Dickens, Ainsworth was the author of 39 novels, mostly on historical themes, and some of his novels (including Jack Sheppard) were adapted to the stage. Ainsworth began researching the novel in 1837, the year Queen Victoria came to the throne. He drew on eighteenth-century press accounts and on popular literature about Sheppard’s criminal career, daring escapes, and ultimate punishment. The author made many revisions and corrections in his autograph manuscript, entitled “True Account of Jack Sheppard the Housebreaker,” in part at Bentley’s insistence. The text often differs from the published novel. Also included in the two volumes are Ainsworth’s research notes about Sheppard, a synopsis and early drafts of the novel, a letter of 1838 to Charles Ollier about Bentley and publication, portraits of Ainsworth and Sheppard, and fragments from the manuscript of the author’s later novel Old St. Paul’s (1841).

The Jack Sheppard manuscript has been added to the Manuscripts Division’s portion of the Parrish Collection. Ainsworth was one of the British authors comprehensively collected by Morris Longstreth Parrish (1867-1944), Class of 1888, a respected Philadelphia businessman, who bequeathed his extraordinary library of Victorian novelists to Princeton. Parrish’s library was at Dormy House, his residence in Pine Valley, New Jersey. In addition to Ainsworth, Parrish collected Charles Dickens, Anthony Trollope, Charles Reade, Charles Kingsley, Dinah Craik, George Eliot, Elizabeth Gaskell, Thomas Hardy, Thomas Hughes, Charles Lever, George Meredith, Robert Louis Stevenson, William Makepeace Thackeray, Lewis Carroll, and other Victorian authors.

In the many decades since the Parrish bequest, the Department of Rare Books and Special Collections has continued to add to enrich Parrish holdings by gift and purchase. Alexander D. Wainwright, Class of 1939, a life-long curator and administrator at the Princeton University Library, played an instrumental role in this acquisitions effort. While the original Parrish bequest included only one Ainsworth letter, the holdings have grown to nearly 300 Ainsworth letters, including the author’s correspondence with Richard Bentley and 18 letters received from other people. The Parrish Collection includes major parts of the autograph manuscripts of Chetwynd Calverley (1876) and Beatrice Tyldesley (1878); and leaves of other manuscripts. The Rare Books portion of the Parrish Collection has editions of all Ainsworth’s novels. The Graphic Arts Collection has Daniel Maclise’s oil portrait of Ainsworth and 3 volumes with Cruikshank’s etchings for Jack Sheppard, with additional pencil drawings.

Other recent additions to manuscript holdings for Parrish authors include selected correspondence of Anthony Trollope, autograph manuscripts by Charles Lever and Wilkie Collins, and a large number of sermons by Charles Kingsley.

For more information about the holdings of the Parrish Collection, contact Public Services, rbsc@princeton.edu

David K. Lewis and Analytical Philosophy

The Manuscripts Division is pleased to announce that the correspondence, manuscripts, and other papers of the philosopher David K. Lewis (1941-2001) have been donated to the Princeton University Library by his widow Stephanie Lewis and are now available for study in the Department of Rare Books and Special Collections. The finding aid for the David K. Lewis Papers (C1520) is available online. Lewis is widely regarded as one of the most important analytic philosophers of the twentieth century. He is the author of Convention (1969), Counterfactuals (1973), On the Plurality of Worlds (1986), Parts of Classes (1991), and over 110 articles. He also published five volumes of collected articles: Philosophical Papers I (1983), Philosophical Papers II (1986), Papers in Philosophical Logic (1998), Papers in Metaphysics and Epistemology (1999), and Papers in Ethics and Social Philosophy (2000). Lewis’s work was highly influential and affected most areas of analytic philosophy. He made significant contributions to philosophy of mind, philosophical logic, philosophy of language, philosophy of science, philosophy of mathematics, epistemology, and metaphysics. His impact and influence was due not merely to the doctrines he defended, but also to the way he framed the philosophical debates in which he engaged. Lewis’s work continues to be widely discussed and remains a central part of contemporary philosophy.

Lewis was a graduate student in philosophy at Harvard University (PhD, 1967), where he studied under Willard Van Orman Quine (1908-2000) and met Stephanie Robinson, Lewis’s future wife and the present donor of the papers. They met in a philosophy of science course taught by J.J.C. Smart, who at the time was visiting Harvard from Australia. In 1966, Lewis accepted an Assistant Professorship at UCLA. In 1970, Lewis became an Associate Professor at Princeton University. He was named Stuart Professor of Philosophy in 1995, and three years later was appointed Class of 1943 University Professor of Philosophy. Lewis and his wife made annual summer trips to Australia from 1971 until his death. Australia became a second home to Lewis, and he became an integral part of the philosophical culture of Australia. Along with the Australian philosopher D. M. Armstrong, Lewis played an important role in reviving metaphysics in the latter half of the twentieth century.

The David K. Lewis Papers include his extensive correspondence with other philosophers and scholars. There are approximately sixteen thousand pages of Lewis’s correspondence, both incoming and outgoing. There is significant volume of correspondence with David Armstrong, J.J.C. Smart, Frank Jackson, Willard Van Orman Quine, Hugh Mellor, Max Cresswell, Allen Hazen, and John Bigelow; as well as smaller amounts of correspondence with R. B. Braithwaite, Peter van Inwagen, Paul Benacerraf, William Alston, Iris Murdoch, Jonathan Bennett, Anthony Appiah, J. Peter Burgess, Paul Churchland, D. C. Dennett, Gareth Evans, Philippa Foot, Margaret Gilbert, Sally Haslanger, Jaakko Hintikka, David Kaplan, Saul A. Kripke, Colin McGinn, Thomas Nagel, Derek Parfit, Steven Pinker, Alvin Plantinga, and many others. Lewis’s letters are often very detailed, as he maintained ongoing conversations regarding many philosophical topics with his colleagues through regular correspondence. Lewis’s writings include drafts of published articles and books, often along with publishing correspondence, reviews, and notes related to each publication. A smaller amount of reviews and unpublished or posthumously published writings are also present, as well as some of Lewis’s undergraduate and graduate student writings, course materials, and notes, including notes from graduate seminars with Donald Williams and others at Harvard and elsewhere, and research files and reports from Lewis’s time as a researcher at the Hudson Institute in the 1960s.

Two research projects now underway make extensive use of the David K. Lewis Papers. The first project is organized by Professor Peter Anstey of the University of Sydney and Stephanie Lewis. They aim to publish the correspondence between Lewis and Armstrong. The second project is The Age of Metaphysical Revolution: David Lewis and His Place in the History of Analytic Philosophy, which is headed by Professor Helen Beebee of the University of Manchester and is funded by the British Arts and Humanities Research Council. The project includes Professor Fraser MacBride of the University of Glasgow as co-investigator, and two postdoctoral researchers: Anthony Fisher, University of Manchester, who provided the biographical information for this blog-post; and Frederique Janssen-Lauret, University of Glasgow. The latter project has the goal of publishing several volumes of Lewis’s correspondence and unpublished papers, as well as a monograph on Lewis and his place in the history of analytic philosophy.

The Manuscripts Division also holds the extensive papers of the eminent mathematical logicians Kurt Gödel (1906-78), C0282, on deposit from the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton; and Alonzo Church (1903-95), C0948, Department of Mathematics. The division also has manuscripts and selected other papers of Princeton philosophy professors Charles Woodruff Shields (1825-1904), C0343; George Tapney Whitney (1871-1938), C0448); and Walter Kaufmann (1921-80), C0469. For information about the David K. Lewis Papers, consult the finding aid. For more information about the holdings of the Manuscripts Division, contact Public Services at rbsc@princeton.edu

David K. Lewis in Cambridge, June 2001,

where he received an honorary D. Litt.

degree from the University of Cambridge.

© Hugh Mellor

You must be logged in to post a comment.