NB: Sorry for the lat post on this session! I am following up on JD again, but have yet to read his thing, since I have been slow to finish my own reflections on our Sebald/Ankersmit/Oppenheimer week.

Really strong thematic resonances sounded through the stuff we prepared for seminar this week. The Ankersmit, for all its faults, frames the problem of “experience” in relation to history with, I think, genuine precision — especially in the introductory chapter. Sebald’s Vertigo activates questions of history and memory as lived/literary experience in a very distinctive way (the narrator can even be understood as something like a fictional figuration of an Ankersmitian seeker-after-sublime-historical-experience). Finally, Oppenheimer’s film (which remains for me one of the very most powerful works of art I feel I have encountered in the last decade) uses a destabilizing series of historical-actor-directed reenactments to bring the issues of history, memory, experience, and trauma into a conjunction so implicating/imperiling that the language of sublimity seems quite appropriate.

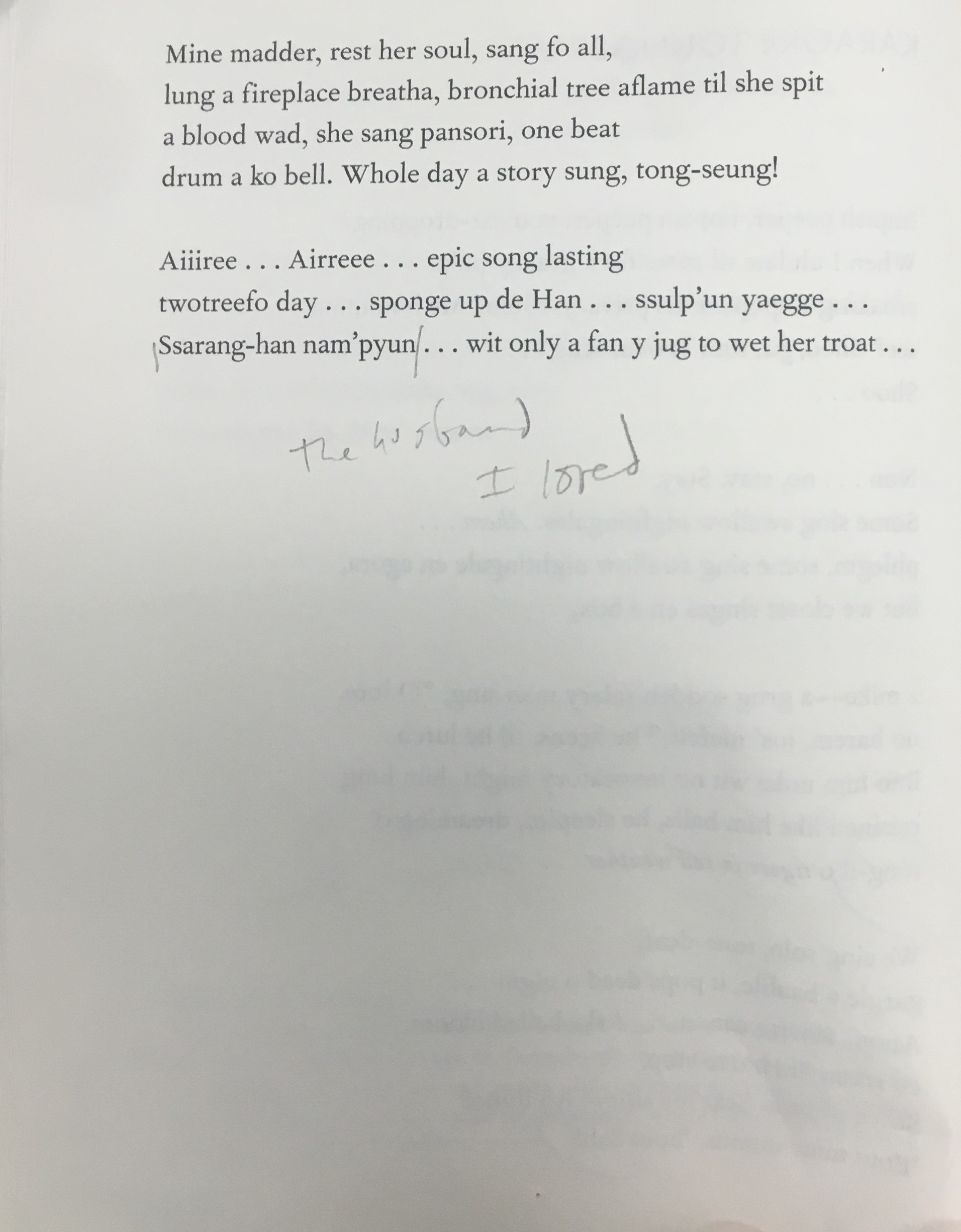

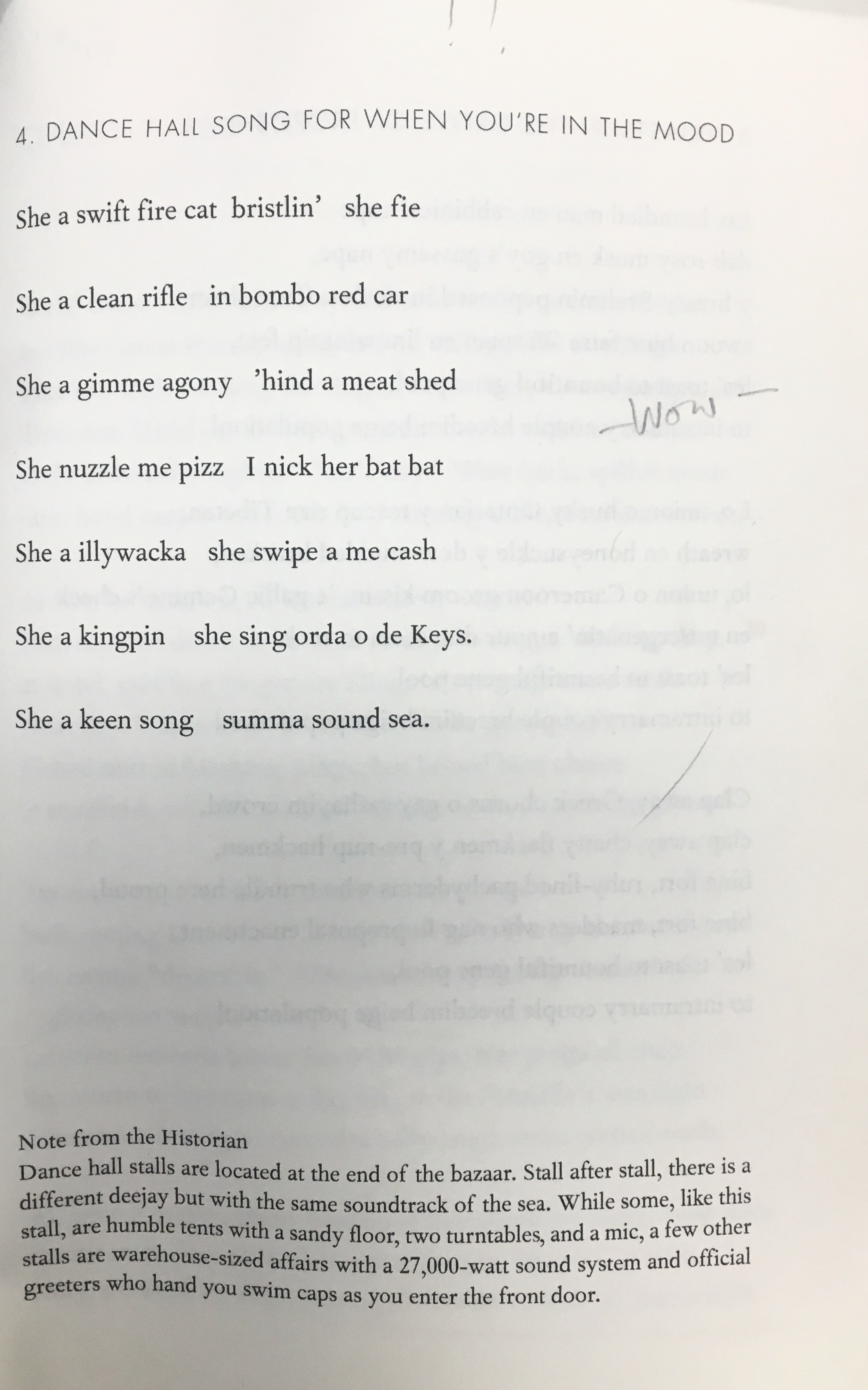

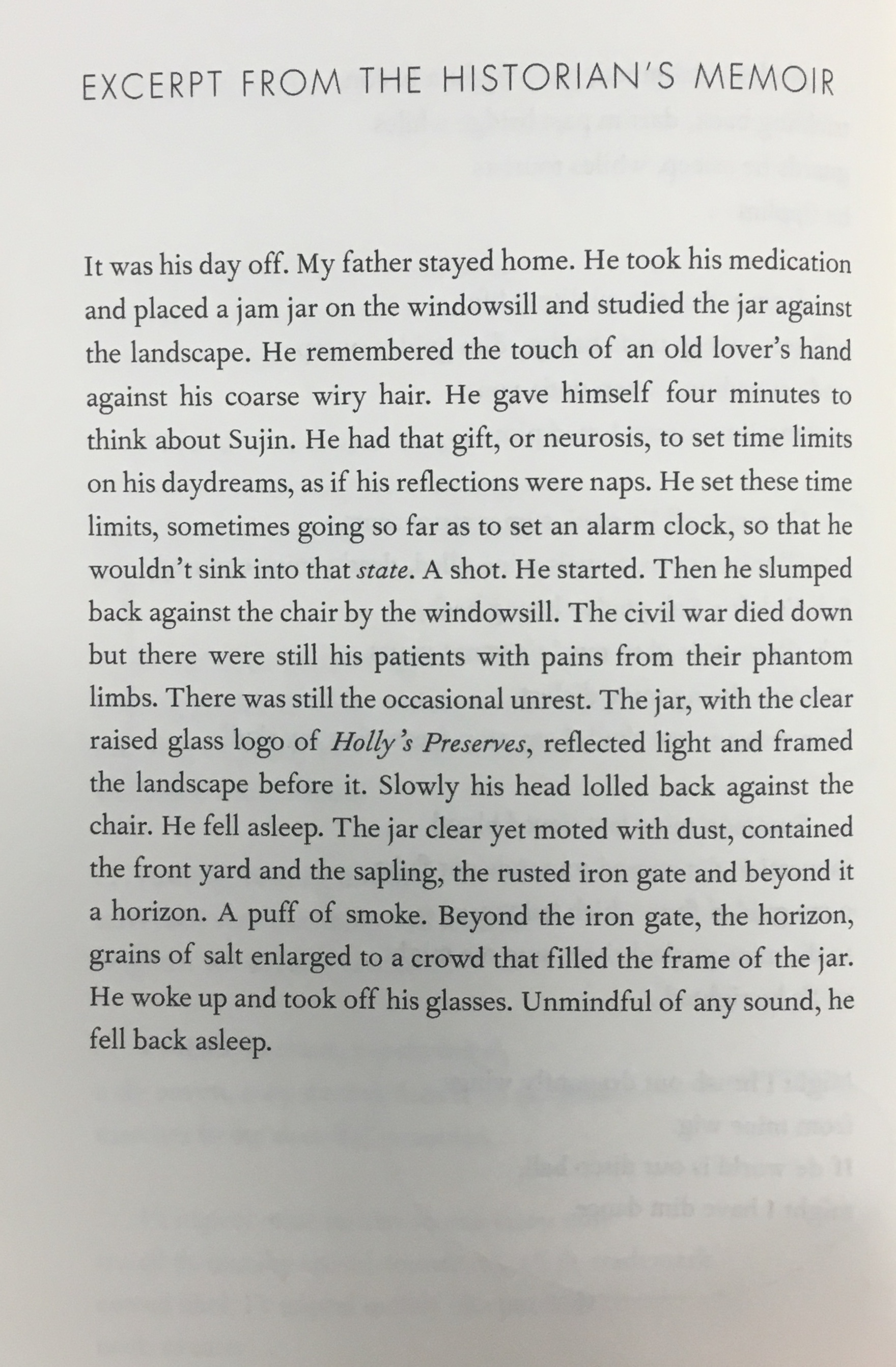

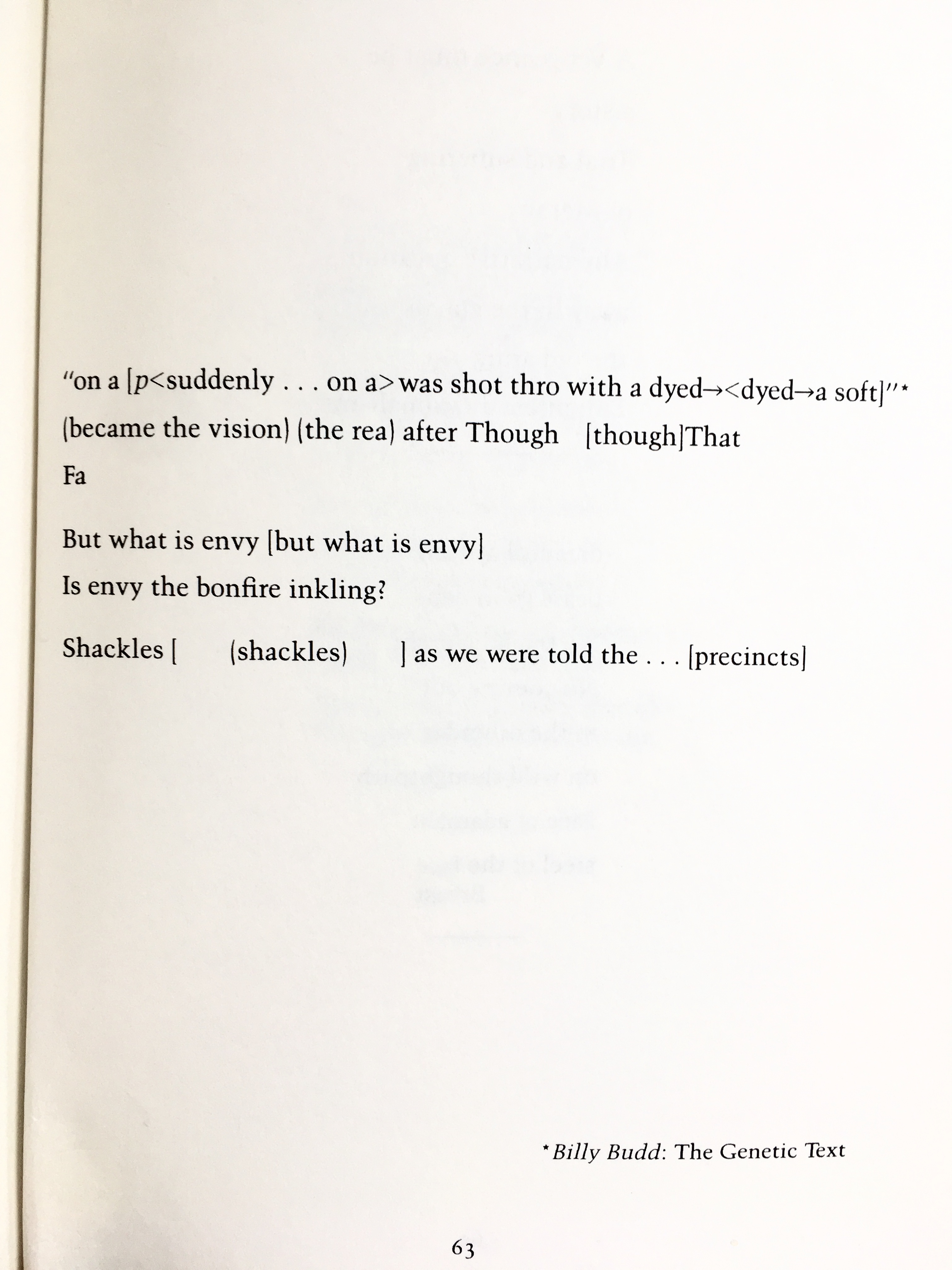

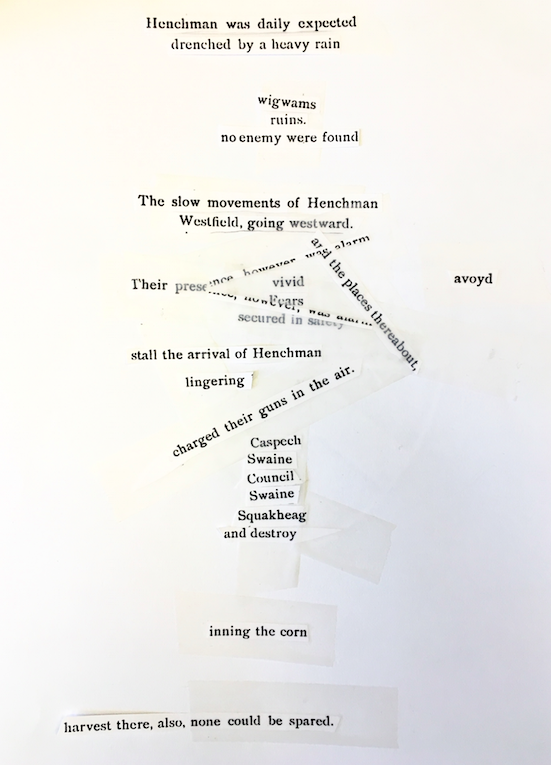

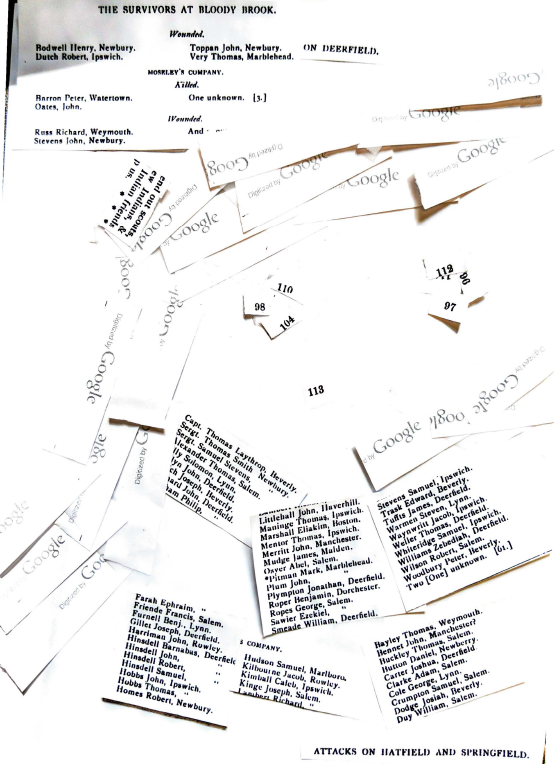

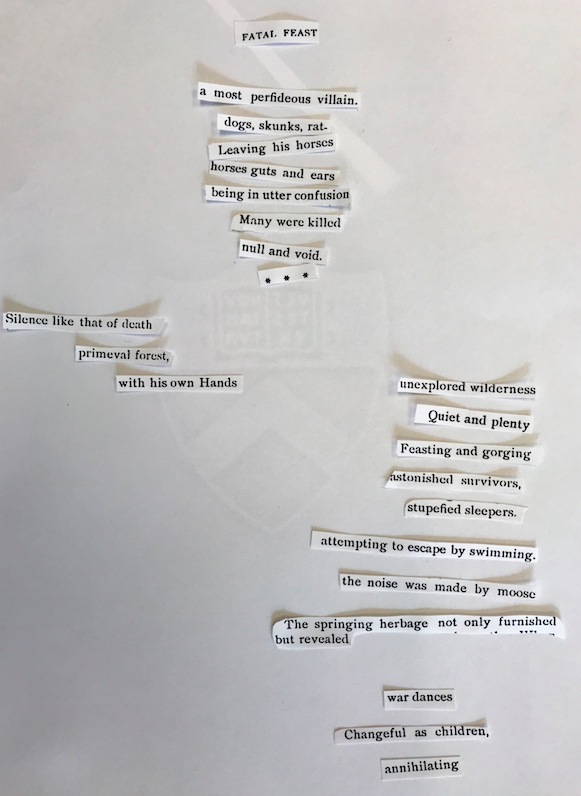

We launched our discussion from the punctum exercises. Recall the assignment this week: “Render your punctum as an experience. That is: make it available to a reader, viewer, listener, not as knowledge; not as narrative, nor argument; not as fact, nor information; but as … experience. You may use language, but bear in mind Ankersmit’s sense of the fundamental antagonism between language and experience.”

There was, I think, a general consensus that there were no easy escape routes by which to slip out of the “prison house of language.”

Lisa brought cinematic technique to her laptop — and by making a documentary screen capture video of her own searches and researches, she succeeded in creating something a little uncanny (since, watched on one’s laptop, it is possible to experience an odd disorientation in relation to what is happening on one’s screen; I mentioned that this effect is used to notable power in Camille Henrot’s “Grosse Fatigue,” about which I wrote here; also, Greg mentioned Kevin B. Lee’s “Transformers: The Premake”; all of this is related to an emergent genre, the “Desktop Documentary” ).

James also used moving images — but in a more archival key. By sifting YouTube for “home-movies” from the region and time he’s thinking about for his punctum, and then by re-cutting and composing those fragments, James created a “vertigo” of sorts: memories that are not his, but that he started to experience as weirdly his own. I was quite drawn to the way this exercise leveraged the new, strange, cosmic scope of the navigable archive-manifold (the ALL). The newness of this phenomenon (and thereby, the newness of our relationship to it), and the broader implications for our “historical consciousness,” cannot be overstated.

Several of you (Jeewon and Fedor) seized on the paper technologies of “administralia” as a mechanism by which to (make words) do something. A “missing persons” form does indeed create/imply an “experience” in a very particular way — a way that is recognizably different from the language work happening in a short story, poem, or historical narrative. Similarly, language in the shape of an examination is also very definitely the occasion for an “experience” — the experience of taking a test.

Greg offered us a richly narrative account of his own multiple/failed(?) punctum exercise efforts this week which included everything from a trip to the emergency room (Gasp! We are glad you are OK!), to running runic laps around the local schoolyard, to filming his desk as he tried to do the punctum exercise (in what would have been a little like what Lisa did, perhaps). In the end (and I think it is forgivable this week), he recurred to the familiar ground of a written commentary — in this case describing how difficult it is to do something other than written commentary.

So there you go.

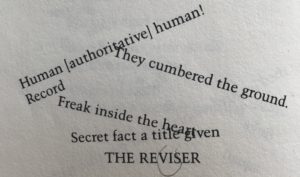

I, too, confessed that I had to fall back on a mere “account” of an experiential relationship to my punctum. My preferred strategy for “creating an experience” — the deployment of that bastard genre of the PROTOCOL, which I think of as something like a “recipe” for making something happen, and hence as a kind of “poetics of experience” — failed me in this instance. I just could not think my way to anything that felt even like a minimally responsible “protocol” for “experiencing” 6 August 1945. I tried. But my spirit rebelled. Anything I came up with felt morally repugnant — even under the sheltering rubric of “experimentation.” So here is what I came up with instead.

As I tried to suggest, my efforts toward my punctum exercise this week definitely had the effect of heightening my sense of confusion concerning the essential nature of “an experience.”

What, exactly is such a thing? The whole matter came to feel like something of a koan. At the same time, the reverie to which this confusion led me (manifest in my exercise above) pleasingly defamiliarized the general enterprise of History in its contemporary academic instantiation. One really could do the whole business a lot of other ways…

I know I say stuff like that a lot. But I think the point bears repeating. Because one cannot really do what one is doing with any meaningful sense of freedom and specificity absent a rich feel for alternatives.

*

We dug in on the materials for the week. I thought conversation around The Act of Killing was a little slower than I might have expected. Dolven was affected, certainly. There was consensus that it was powerful. But I did not sense a rush of strong feeling either way from most of you. I am still a bit puzzled by that. I went back to my notes from the last time I assigned this film in a grad seminar. I am going to link to that discussion here.

Different context. But you can feel the momentum of engagement. And nothing like that quite happened in our session. Yes. Anwar retching hits hard. James and Lisa helpfully held off my gambit that the film ultimately conforms to a (very powerful, but also fundamentally conventional?) structure of contrition/redemption. Working closely with the cinematic language of the climactic scene (the revisiting of that swept-clean terrace where so many of the killings happened), they argued that the camera’s remaining in the space, as Anwar departs, must be read as an expression of the commitment/perspective of the work—which is, finally, with the victims, not with the story of self-transformation through contrition (those of you who want to see Oppenheimer deal directly with the question of victimhood should consider the “sequel” to The Act of Killing — the film The Look of Silence).

It is an important proposition. I want to watch it again with this in mind.

Though it is hard to say that one “wants” to watch the film. Since it is, I think we all agreed, almost unbearable.

Jeewon was interestingly and articulately resistant (is this the right word?) to the film’s powers/virtues — even as he seemed to acknowledge both. The strained question of just who “Joshua Oppenheimer” is/was… lingered for Jeewon. And also questions around the funding for the film. And the issues of insider/outsider, of wealth and power (of race and ethnicity?) — these too were in the air for Jeewon, in ways that he wanted us to consider. No denunciations here. But questions.

Closer to a denunciation? The issue of the ethical implications/consequences of the more brutal and traumatic scenes of reenactment. This was indeed hard to take without compunction.

But in and across all of this, Dolven powerfully asked us to remain sensitive to the extent to which the film “had control” over the domains in which these questions could be found and raised. The posing of the questions could be said to be happening in terms that the film afforded. And this, Dolven suggested, is one of the significant hallmarks of a true work of art.

We took our break.

*

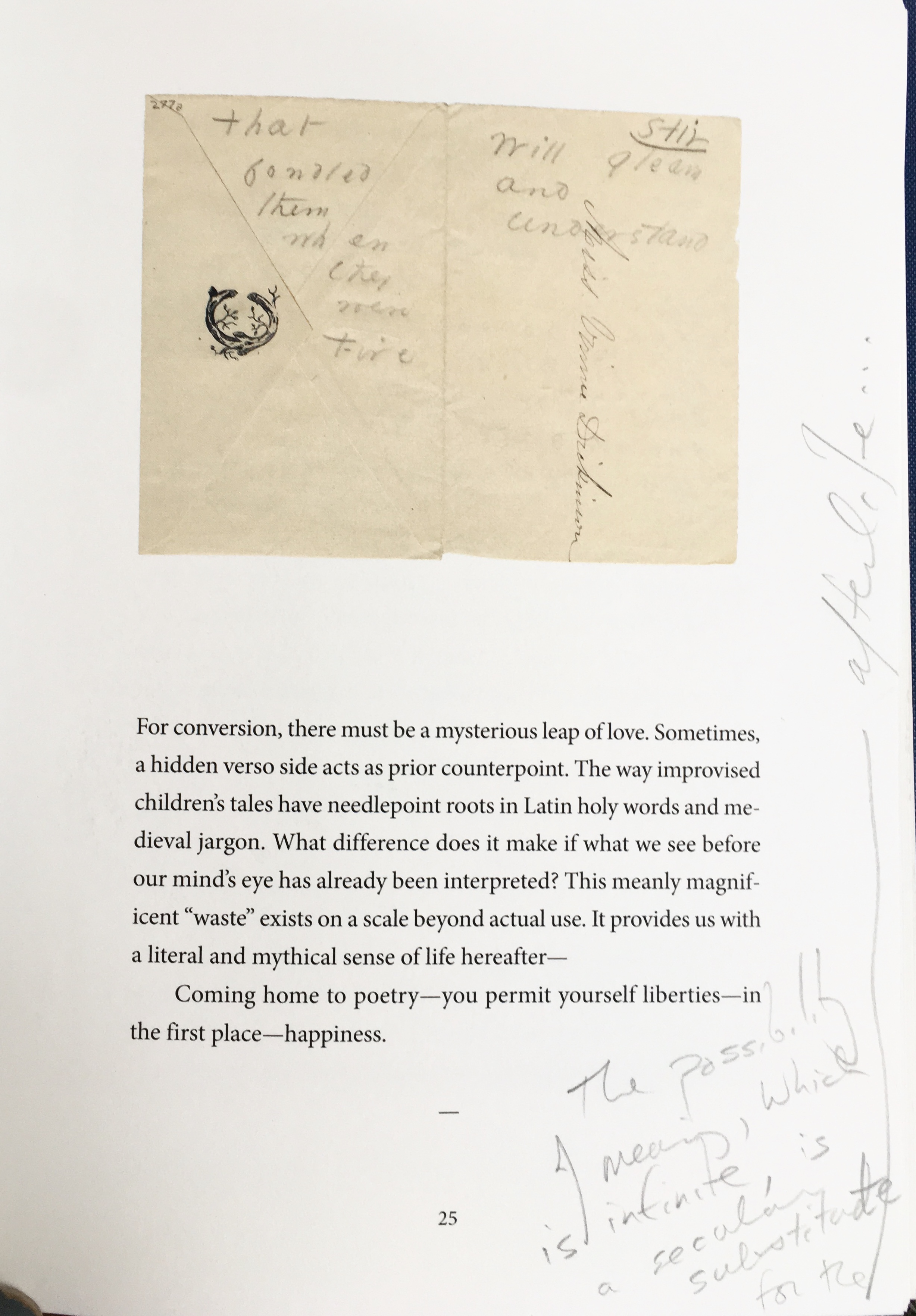

When we reconvened, we took up Vertigo. “Experience” remained a key term in our discussion — and we threaded back to Ankersmit repeatedly over the course of the conversation. Once again, I have snatches of our discussion inscribed on the flyleaf of my copy:

There is no flow without telos.

It is a book of doppelgangers.

Memory/remembering as an ALTERNATIVE to “history” — explanation is, thereby, elided.

If, in the end, representation DESTROYS memory, then this whole project is perfectly perverse.

VAGRANT PRAXIS — repeated, wandering efforts to line up past and present.

Finding any means to make memory possible seems to be the issue.

Is this text avid to make connections? (or afraid of them?)

The longing for a return to childhood (where not knowing history could be excused/forgiven/easy)

Circled in the middle of my back cover is a phrase that I believe Jeewon introduced to the discussion, and that stuck with me: “weak humanism.” I circled that phrase. My recollection is that Jeewon introduced the proposition in a context slightly different from the work I later wanted to make it do, but, for me, the notion helpfully captured something of what I came to sense as a central paradox of this novel.

I closed Vertigo with a very strong feeling of its achievement. I take Sebald to have used language to “show (the human) spirit to itself” in a genuinely novel/unique way. This book and his others actually capture something of the “stream of (historical) consciousness” as lived/subjective experience. Just as Joyce used language to mirror features of psychological/linguistic “inwardness” (and in doing so created a very different kind of novel), Sebald has a claim, I think, to have conjured something comparably new/distinctive. Joyce gave us the modernist consciousness as a kind of annulus through which everything passed; Sebald gives us post-modern consciousness as an empty opacity lightly drifting hither and yon on the conflicting tides and surging eddies of continuous macro-mechanical/violent change.

Ismael was moved. As he put it, “I experience it being like this.” And I think he meant that he experiences consciousness itself as being something very much like the consciousness Sebald depicts/invokes/conveys in Vertigo.

Greg, by contrast, demurred. Perhaps not. Perhaps being here does not feel quite like this — like a morose and ennobling chorographic nostalgus interruptus.

But even if one recoils from the gentle/hapless anomie of this ever-so-earnest lost soul and his empty-handed grasping at phantasms (or is it at the feelings of phantasms?), I think one must acknowledge that one has been forced to confront/inhabit a form of life.

For my part, though I cannot say that I genuinely enjoyed the book (the sense of pointlessness engendered by the drifting by both the character and the elements of the story left me mostly cold), I very definitely wandered around for several days after finishing it with a strong sense of having met a thing that a human being is/can-be/was.

I stick “was” in there advisedly, since I am inclined to feel that the book invokes a kind of personhood that is mostly no longer that relevant. What do I mean? Well, I mean that the extravagant inwardness Sebald achieves in his narrator feels to me like an endgame proposition. Downward to darkness on extended wing (and slightly disoriented) slips the bookish, historically-minded, self-archiving, older-white-European-male. The relationship with memory that he instantiates, and that Sebald dramatizes, is basically yesterday’s problem for yesterday’s form of historical figure.

Much as Susan Howe’s archive-reverie listening to the hum of the HVAC within the tomb of Beinecke Library could feel a little like a form of archive-intimacy mostly irrelevant to those of us who increasingly access the manifold on a laptop while listening to music in a coffee shop; so, too, some German guy with a mustache checking into a cheap pension in Venice while thinking about Winkelmann (or whatever) in a lonely sort of way cannot be said, I think, to go to the heart of the problem of historical consciousness for our time (please see The Act of Killing…).

But one mustn’t be glib.

The phrase “weak humanism” promises a richer way to evoke what I am getting at.

Veritgo very definitely offers an exquisite evocation of the human in its recognizably “humanistic” avatar — but right as that “build” sort of sinks into the quicksand. “Weak humanism” is humanism humbled, chastened, and in the exeunt omnes phase of the drama. One feels some measure of pity and some measure of the delicacy of an old and imperfect hero closing those watery eyes.

There is no final “thumbs-up” here as the upstretched arm vanishes into the boil (promising us a sequel?) — rather, we glimpse only a sort of ambiguous, open-handed gesture, maybe trying to offer us something, maybe reaching, not very persuasively, for help (which is not forthcoming).

But that final gesture could also be a kind of shrug.

It felt a little like that to me at times…

*

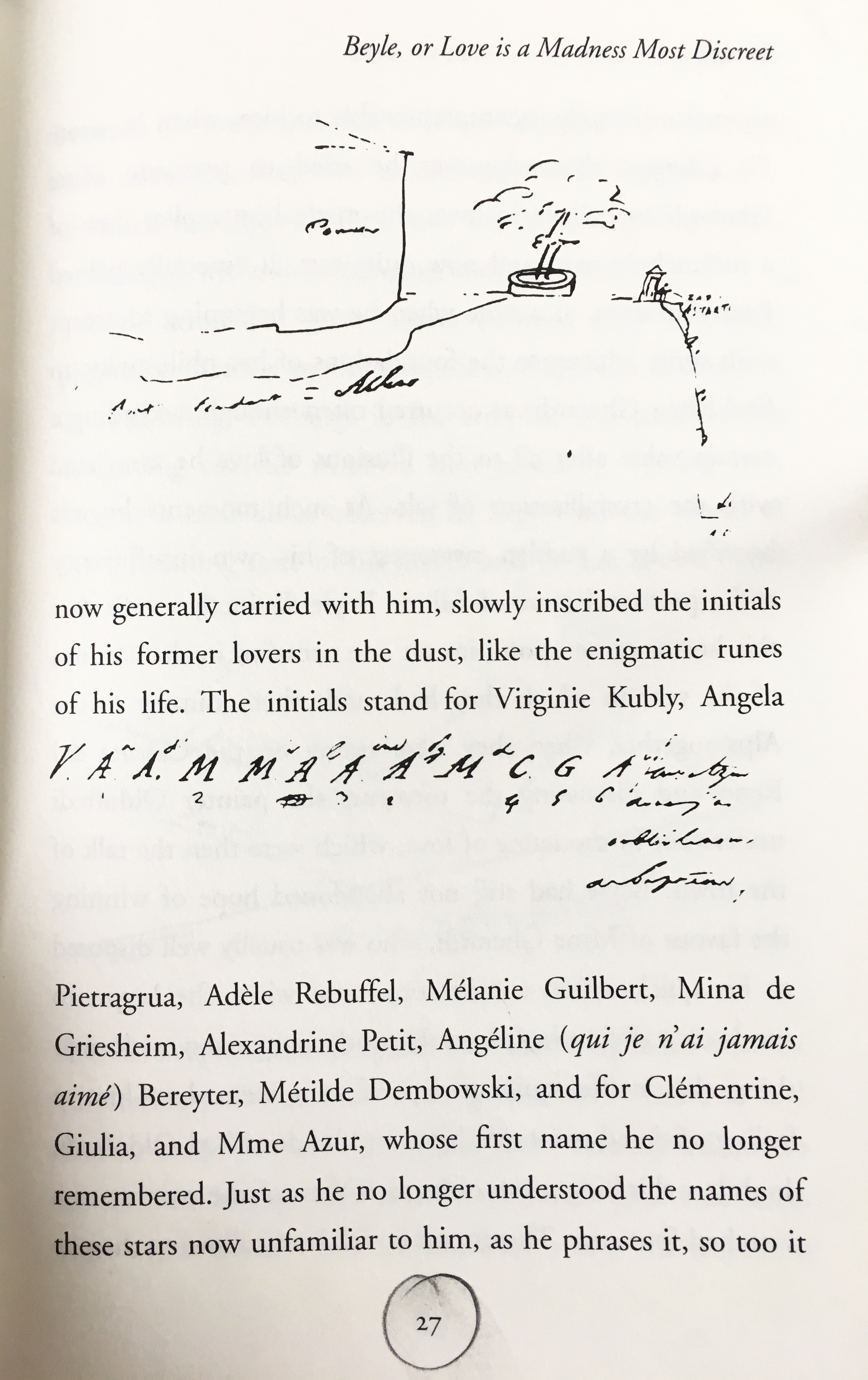

There are two moments in the novel that I think can function as thematic set pieces. We discussed both of them in some detail. The first is here:

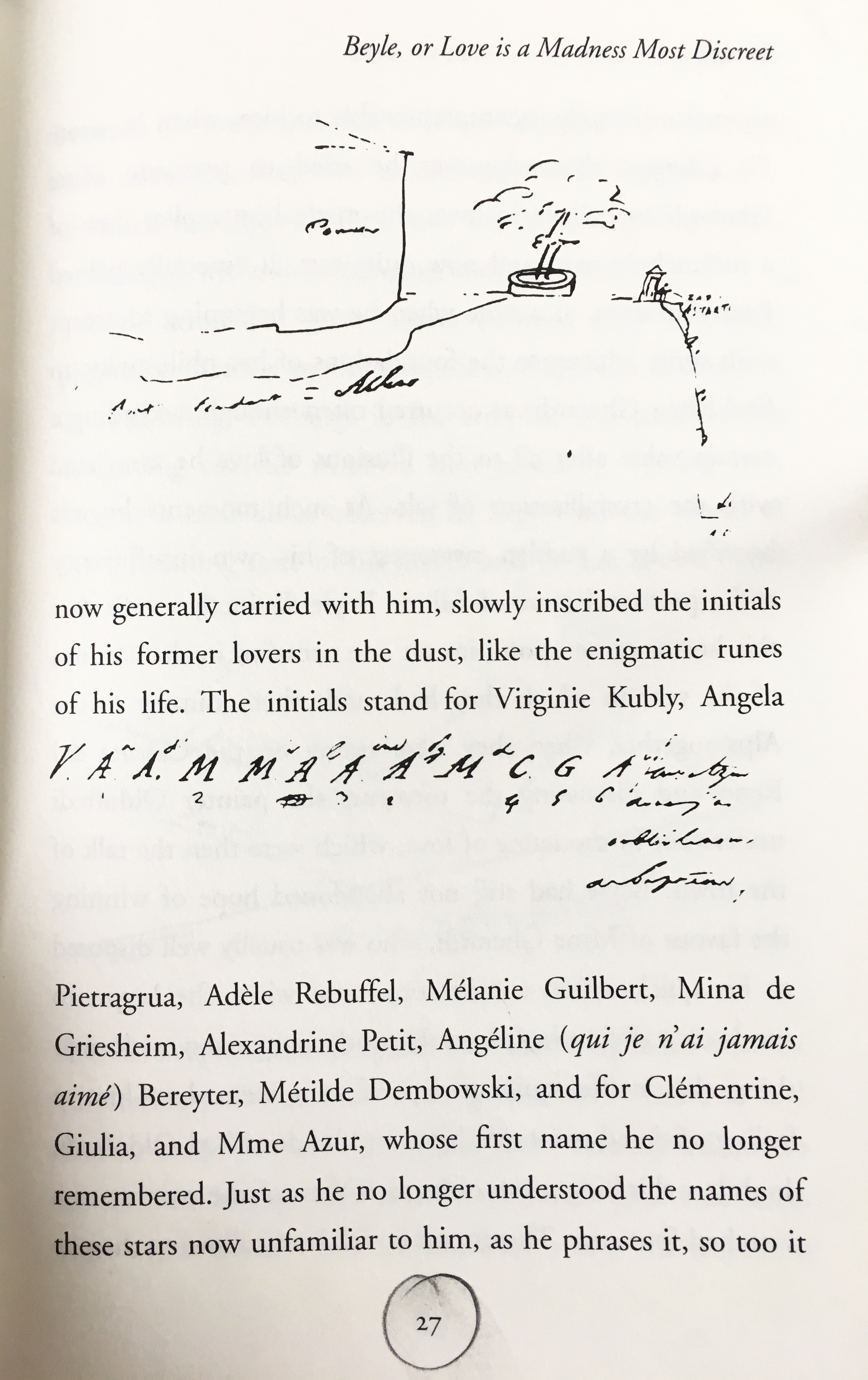

This, above, recall, purports to be a sketch drawn by Marie-Henri Beyle (Stendhal himself), depicting a memory-reverie of his own (and reprised here in the course of the narrator’s own memory-reverie).

The moment of “vertigo” lies in the narrator’s observation that Beyle has depicted the scene from a position he did not occupy — he has depicted himself “in the scene,” but from without. Much of Vertigo can be understood to be disoriented by the historical equivalent of this spatio-perspectival problem.

Again and again we sense the author feeling confused about his own “in-the-scene-ness” of the past (then? now?), and apparently endeavoring to bring the outsider and insider perspectives into some kind of conjunction. Whatever that communion might be, it is perpetually deferred, and the subtending confusion as to what it might actually consist in prevents even its deferral from exerting the organizing libidinal impetus of a proper desire. When the past actually does irrupt into the present (as it does here and there — as when suddenly one is sitting across from King Ludwig II of Bavaria on a train, or when the young Kafka appears in duplicate in the back of a bus), an immediate diminuendo of absurdity and misunderstanding instantly attenuates whatever fleeting satisfaction might have been had. Or, rather, a proleptic diminuendo (the ready state of a subject too uncertain to trust his own intuitions or appetites) suspends both the epiphanic and the ghostly registers of any such “intimacy” in a grey miasma of awkward impotence, shame, and confusion.

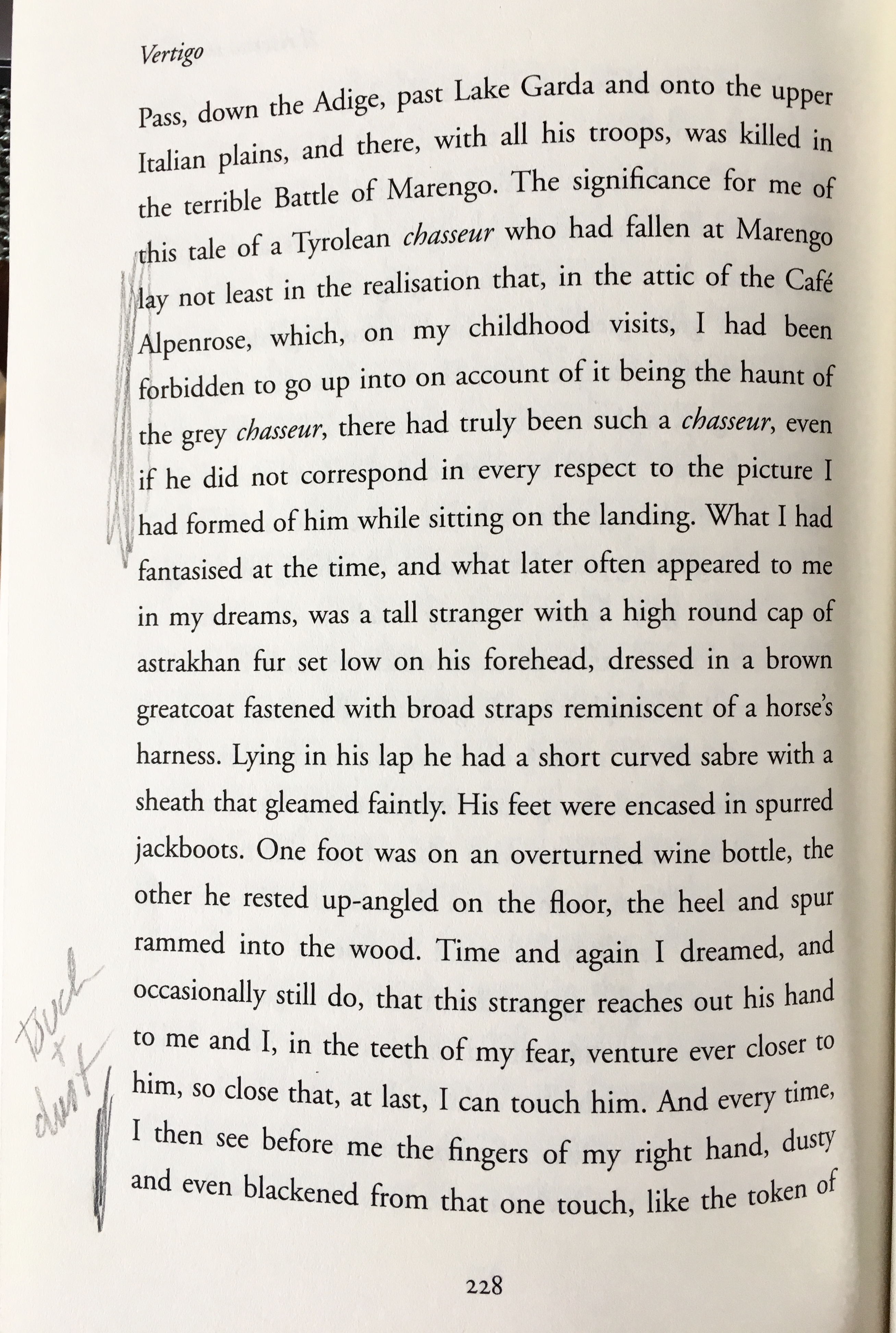

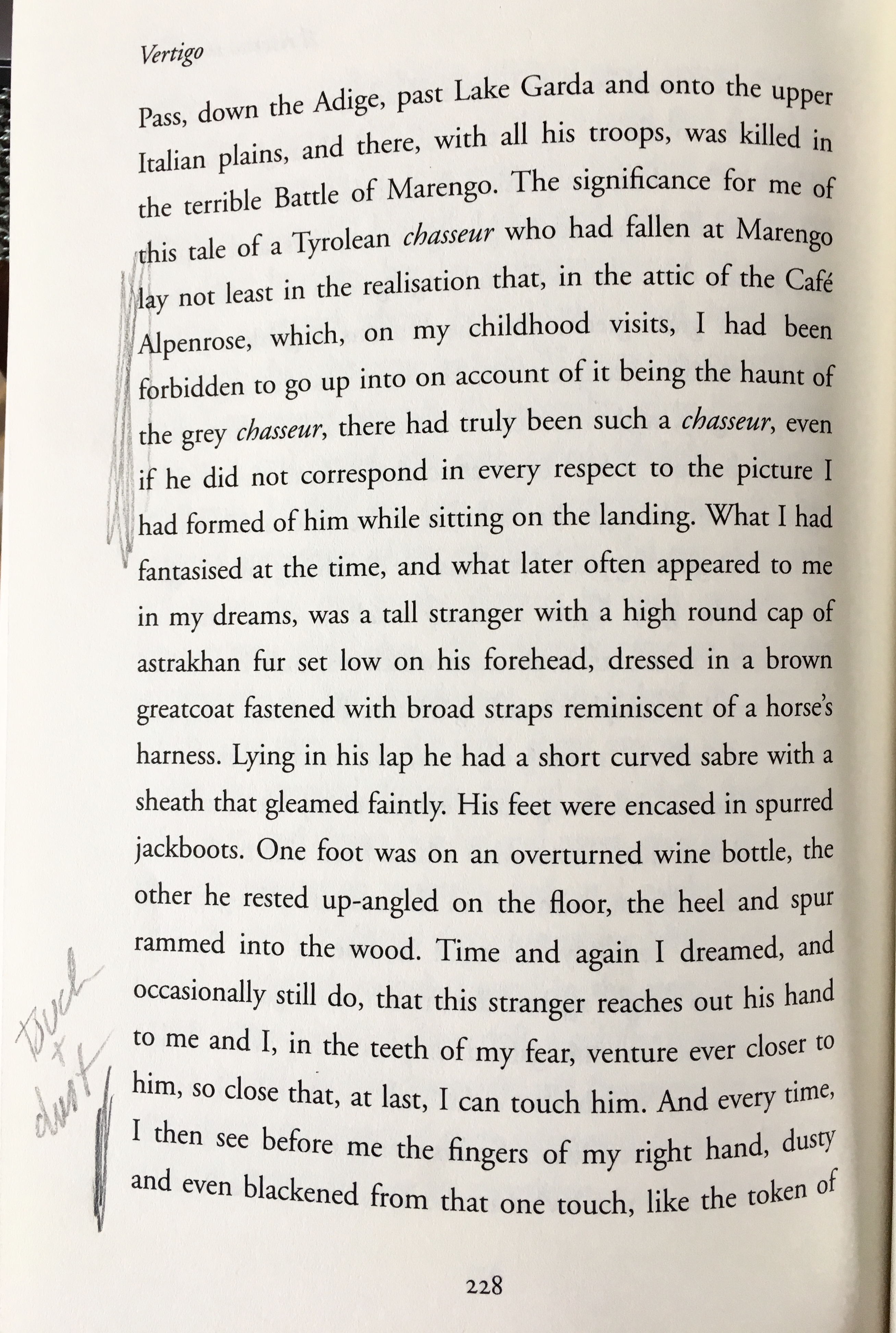

I said that there were two moments that can function as set pieces. I take this to be the other one, which is also, I think, a thematic nucleus of the novel:

What do we have here? It comes perilously close to functioning, I think, as an allegory of the whole project of the book: the past haunts us as a kind of formless/nameless bogey; we are drawn inexorably back toward it, in an almost childlike/dreamlike way; queer moments of sudden intimacy with this history-succubus are (almost) possible, but no sooner is some kind of “contact” actually made, than the very act of intimacy itself instantly causes a collapse/evaporation/falling-away of the historical object. The net effect of all of this is a little grey dust-smudge and a sense of loss/confusion/failure. (To be fair, I have cut off a sentence at the end of this page, and it finishes, “some great woe that nothing in the world will ever put right” — which certainly indicates that there are stakes).

I do not mean to tie the whole thing off with a bow, but it really does seem, even with that indelible smudge, a little tidy.

*

Indeed, at about this time one could, I think, start to feel a little testy about the whole enterprise. One could even get a premonition of some of the controversies that would later (well post-Vertigo) dog the Sebaldian enterprise (e.g., discussions around The Natural History of Destruction).

The After all, is it really quite so simple? Quite so “easy”? The past doesn’t actually dissolve into smudgy powder-dust with a light brush from the hand of an old white German guy. Actually, there are some intractable legacies — durable, dense, barbed. Hello? DO YOU READ ME?

While this kind of critique did not really get rolling with any genuine momentum in our class discussion, it did float, for me, over the latter phase of our seminar. And it had implications for our thinking about the Ankersmit as well.

While I continue to feel that the first chapter of the Ankersmit lays out a very significant problem for historical thinkers, I expressed considerable frustration with what Sublime Historical Experience actually finds itself saying and doing by the end.

Hölderlin? Really? Are you SERIOUS? The effort to discern something — ANYTHING! — that can be said to stand beyond or beneath or against the typhoon-totalizing (non)reality of language winds its way to another freaking teary-eyed Teuton musing about the lyric of Hölderlin? Again? REALLY???

[visualize emoji of Munch’s Scream, but with Munch’s Scream faces for eyeballs, each of which faces has more Munch-Scream-faces for eyeballs all the way down – in a kind of Pokemon-mise-en-abyme]

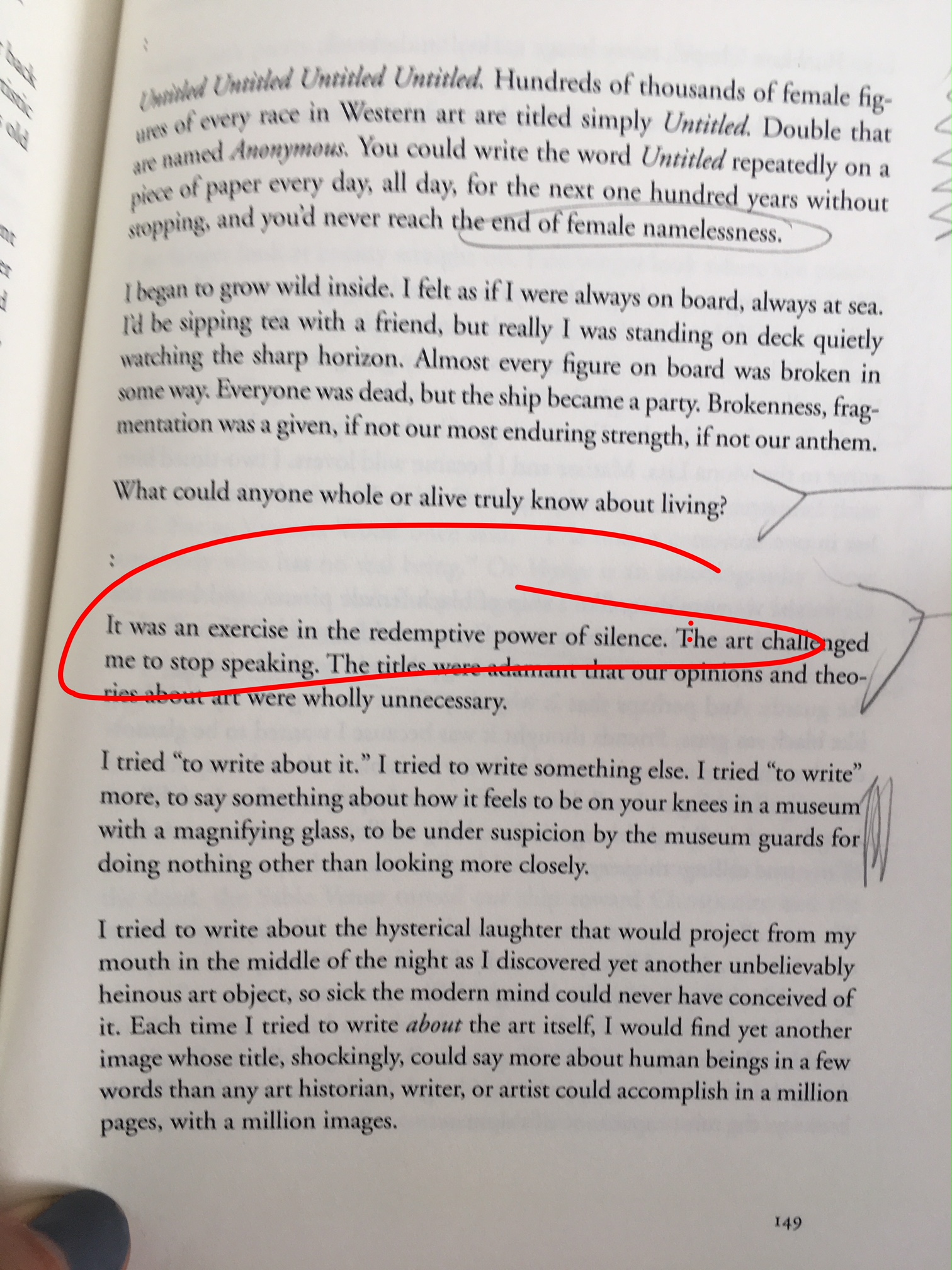

It is enough to make one side with the most virulent critics of the “experiential turn.” I am thinking, for instance, of Joan W. Scott’s hard-hitting essay “The Evidence of Experience” from 1991, where the we are warned that the language of experience can easily function to veil exactly the categories most in need of critical scrutiny. She concludes:

What counts as experience is neither self-evident nor straightforward; it is always contested, and always therefore political. The study of experience, therefore, must call into question its originary status in historical explanation. This will happen when historians take as their project not the reproduction and transmission of knowledge said to be arrived at through experience, but the analysis of the production of that knowledge itself. Such an analysis would constitute a genuinely nonfoundational history, one which retains its explanatory power and its interest in change but does not stand on or reproduce naturalized categories.

Or take a look at Michael S. Roth’s very forceful (and ultimately negative) review of Ankersmit’s book itself. Roth quotes Ankersmit on the promise of sublime historical experience (“Historical experience pulls the faces of the past and present together in a short but ecstatic kiss,” from p. 121), and then tells us that he (Ankersmit) quickly wants to reassure us that “this certainly does not imply that we have now entered the domain of mysticism and irrationality.” Except, as Roth icily notes, “It seems to this reader that this is precisely the domain that Ankersmit has been forced to enter, for this is the only alternative he has left himself after rejecting pragmatism, hermeneutics, and the problematics of representation.”

It is a stinging charge. Clear and direct. And it demands to be reckoned with. Especially by those of us (and I am calling myself out here) who again and again want to toe up to the very edgey-edge-edge of exactly that threshold. And you all, having endeavored some of the exercises we do in this class, may well have come to feel you have yourselves wandered (been pushed?) pretty close to that edge.

Well, here is what I have to say about all of this:

Disappointed as I am with the Ankersmit, I do believe, in the end, that his work fails in a genuinely noble and absolutely necessary quest. It falls to us, I believe, to stay at this quixotic urgency — and this class has been (is), for me, centrally ABOUT that. It IS that for me.

Why? How?

If Roth is right, the task isn’t “quixotic” in some noble-folly way. It is just stupid and wrong-headed and even reactionary.

Correct. But I don’t think, in the end, that Roth is right.

For here is where he comes out, at the end: “As the tide of language recedes, we may find many things, but I can’t see that purity and a direct connection to the world through something deep and authentic in our souls is among them.”

And you know what? If that is what you think, I am not with you.

Because I think that “a direct connection to the world” is exactly what human beings need. It is what, above all, we seek. We are made of that longing. And the profound longing for exactly such a connection isn’t going to go away because we have now read some Foucault. Or, for that matter, some Derrida.

And so if the world of historical scholarship renounces that notion of a “direct connection to the world” as simple naiveté, historical scholarship renounces service to what is deepest in human beings. And others (who may or may not be scrupulous or sensitive or good or knowledgeable) will address those needs — without the historians.

I think this would be very unfortunate.

And so, we go onward, working to fail well at something very hard. Something worth attempting. Again and again.

-DGB