Cathy Park Hong’s Dance Dance Revolution is an extraordinary work.

I felt that very strongly as I came into the classroom for our final meeting of the semester. Now, in the wake of our closing discussions, I am the more deeply moved by a sense of having been gifted with her tremendous achievement.

Two important insights that came early in our conversation extended my vision.

First, there was Jeremy’s striking comment that memory feels so remarkably secure here in this book, even as both place and language are so manifestly labile (possibly perilous). What a contrast with Sebald! And in the context of that contrast, one suddenly sees that Sebald’s works have precisely the opposite structure: in Vertigo the narrator’s language is measured, precise, reliable; and the terrain (tired old European places) couldn’t be more blatant and conventional; both language and place are rock solid. Memory however, is everywhere fugitive, fleeting, uncertain.

This observation landed with on me with the force of a real and clarifying counterpoint.

The other early moment that palpably pushed my sense of Dance Dance Revolution was Dolven’s underlining of the extent to which the “Historian” figure must be understood to be engaged not only in a general genealogical inquiry (i.e., a questing after something of his/her “pre-origins” through the ethnographic pursuit of his/her father’s lover), but also in an effort to recover/recuperate some connection to an actual tradition of political resistance/solidarity (given the history of the Kwangju Uprising). This is obviously true and important — but I had somehow missed it (probably in the course of all that demanding work trying to parse “Desert Creole” and generally trying to keep track of a pretty intricate plot — one that is by no means easy to work out, given the polyglot delirium and layered voices of this book).

Once one is holding firmly to this idea that the work of the Historian in the story is to try to use genealogical inquiry to establish some form of connection to a meaningful moment of emancipatory politics, the immediacy and urgency of the book’s project squirm with new vigor. The relevance of the book to our questions (about poetics and historical inquiry; about alternative forms of historical consciousness; about the political implications of these various forms of historicity) is felt with still greater keenness.

Not that the relevance didn’t feel pretty keen to begin with.

It is hard to imagine a more powerful conceit for thinking about representation, history, politics, and language than Hong’s Blade-runner-meets-Babel scenario: her volume successfully voices a trans-historical, transnational patois of the disenfranchised of the globe, and that must be said to address the “poetics of history” with uncommon specificity.

*

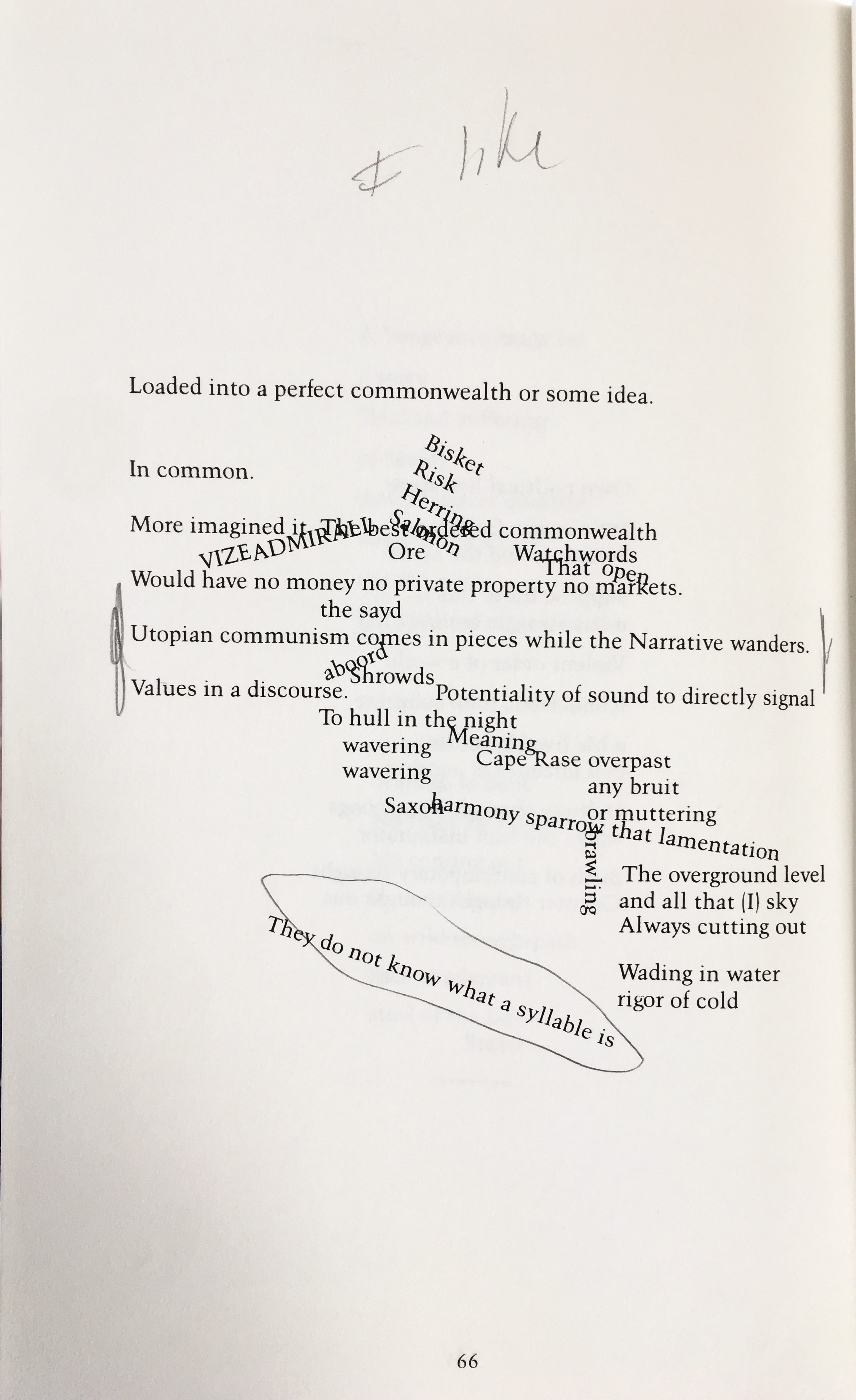

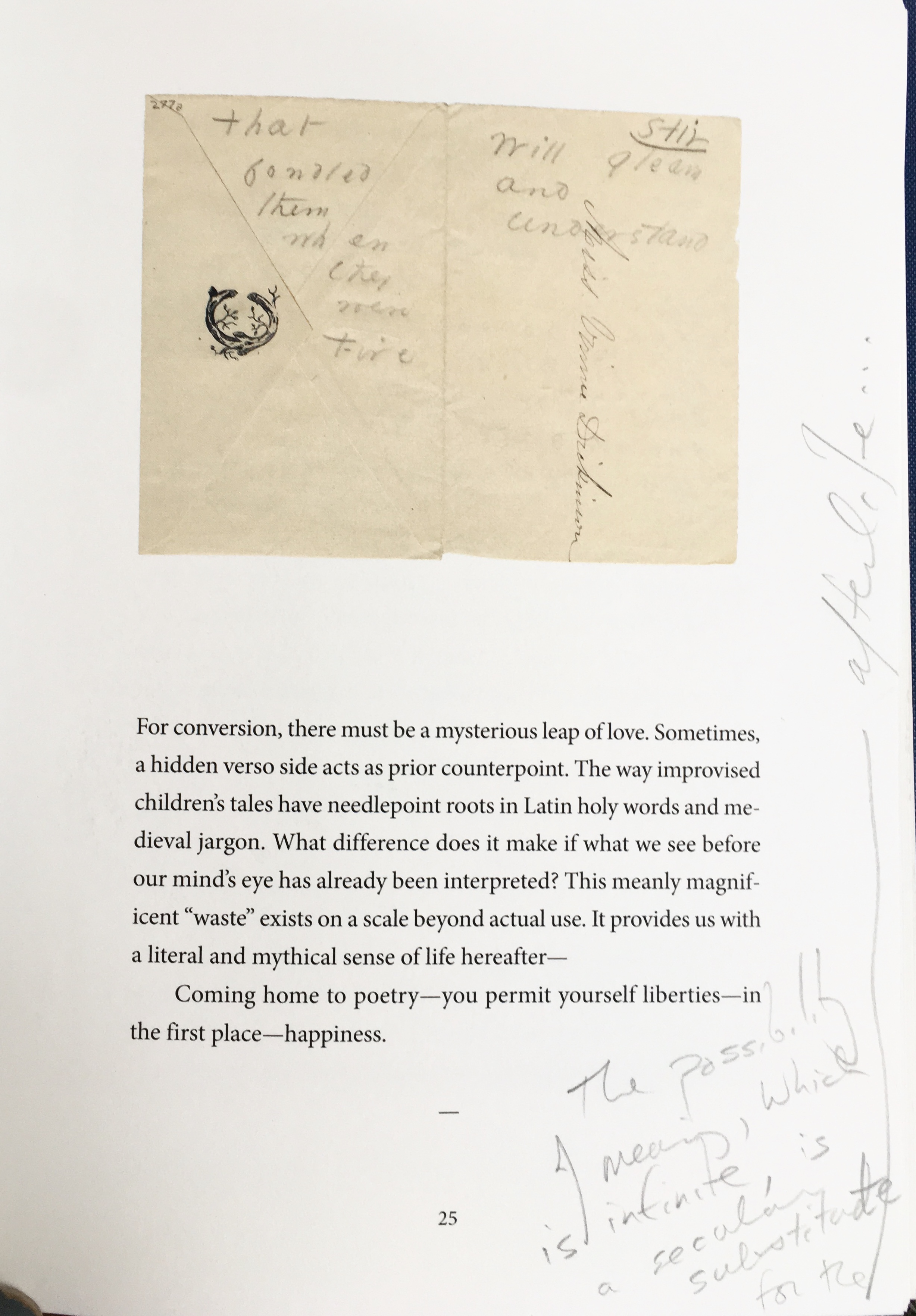

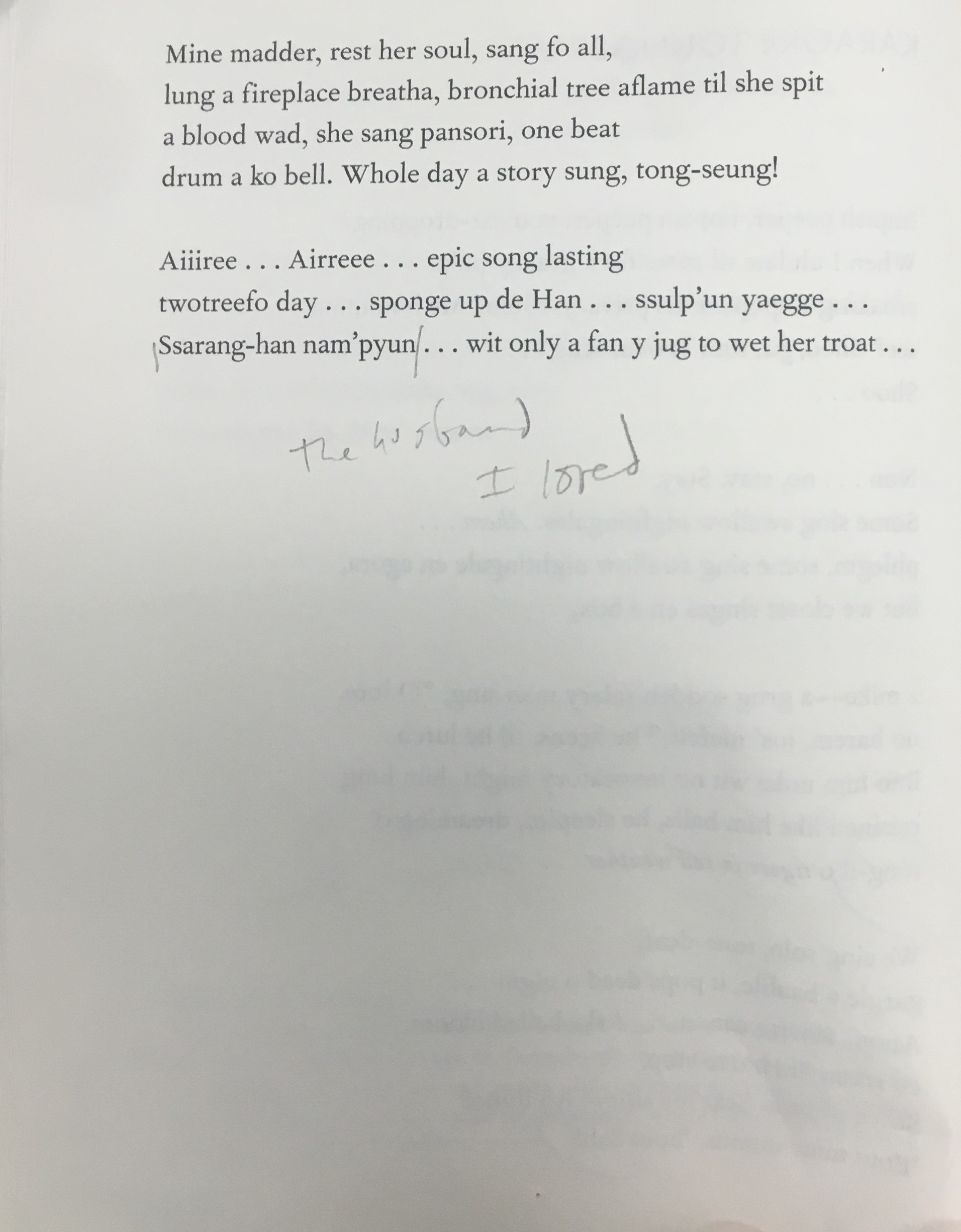

We went in here:

And because this poem was one of a relatively small number of pieces in the book not written in the challenging language of the Guide, we moved into a discussion of the “Intermission” section of the volume (pages 69-84), in an effort to understand the status of these evidently (more) “conventional” works of contemporary poetry. How to account for this “middle voice” — neither the expository writing of the Historian nor the phonetic tangle of the Guide’s pidgin?

Several alternatives were offered, ranging from the suggestion that we might be getting some of Hong’s authorial voice in those pieces, across to the interesting idea that the very notion of the almanac in a desert (where there is minimal seasonality and little to no “growing” at all) should be understood as perfectly oxymoronic.

My own feel for the Intermission section (which had troubled me) was much improved when I tried to read these works as the Historian’s somewhat mannered poetizing recapitulation of aspects of his/her research work with and around the Guide.

As far as “The Auctioneer’s Woo” is concerned, it led us to reflection on the implications of the “privatization” of language — in a literal sense. Elements of the language of the Desert are evidently bought and sold, perhaps accounting for some measure of the continuous, rapid mutation of the speech in this trading zone (where one must be careful not to use a word that is owned by someone else, and hence perhaps subject to some royalty fee or other entailment).

Could the sale of the phrase “may I have this dance” (recounted in “The Auctioneer’s Woo”) account for Guide’s fetchingly mangled valediction at the end of this book (p. 119): “If de world is our disco ball, / might I have dim dance”?

It is an amazing thing to think about: the twisting, knotty, archaic-demotic lingo of the Desert as perpetually shifting across an impossible “mine”/field (feel the pun here — seldom do explosives and possessives feel so close…) of traps and tricks and pitfalls. As the Guide puts it at one point (this is the conclusion of “Years in the Ginseng Colony”):

*

Jeremy made a stinging observation on this dystopian vision of a slippery, traducing, (un)free market for language: he said that, informed by his readings of Wittgenstein, he inclined toward conceiving of language as a kind of “public property” — created by all, available to all, functioning to unify people’s shared domains of sense-making. What a contrast in Dance Dance Revolution, which confronts that Wittgenstinian intuition with a hyper-particularizing and private cant, a language in which every voice a personal palimpsest (layered by cash-money).

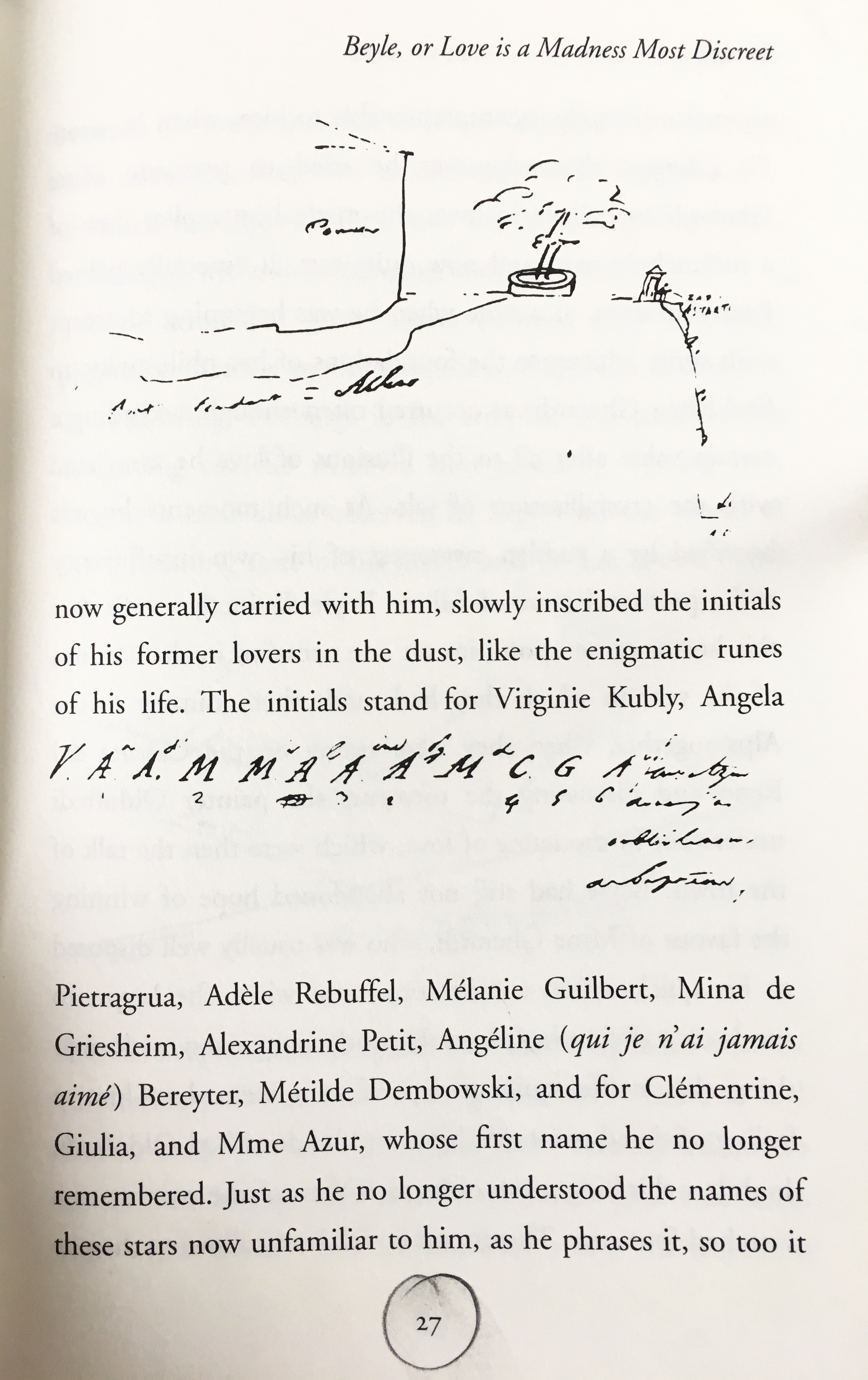

The density and intricacy of that palimpsest were very much in evidence when we tapped Jeewon’s philological expertise in the Korean language, and watched him unfold the multi-lingual punning and trickery that percolates along beneath the threshold of perception of those without any Japanese/Chinese/Korean.

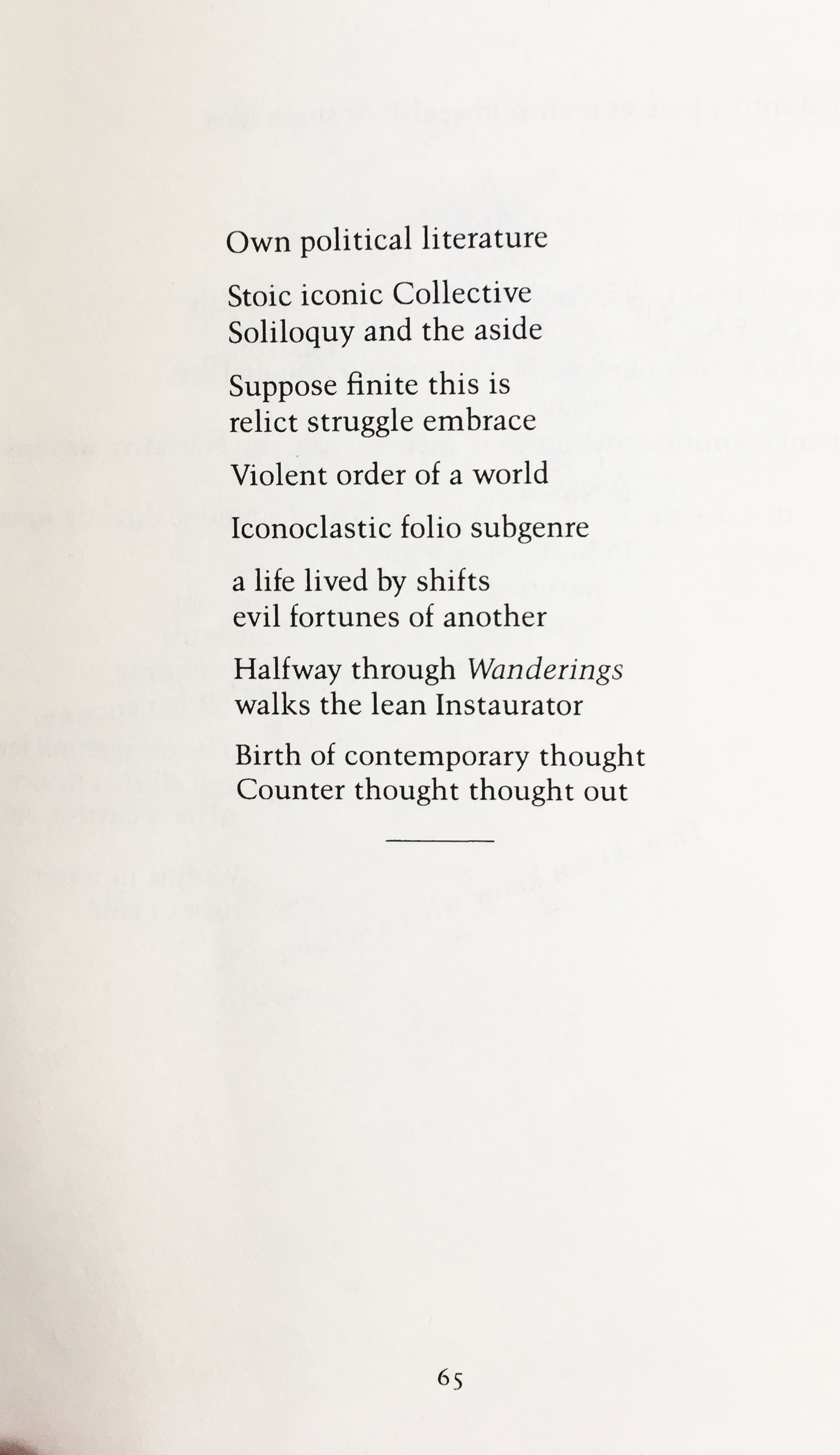

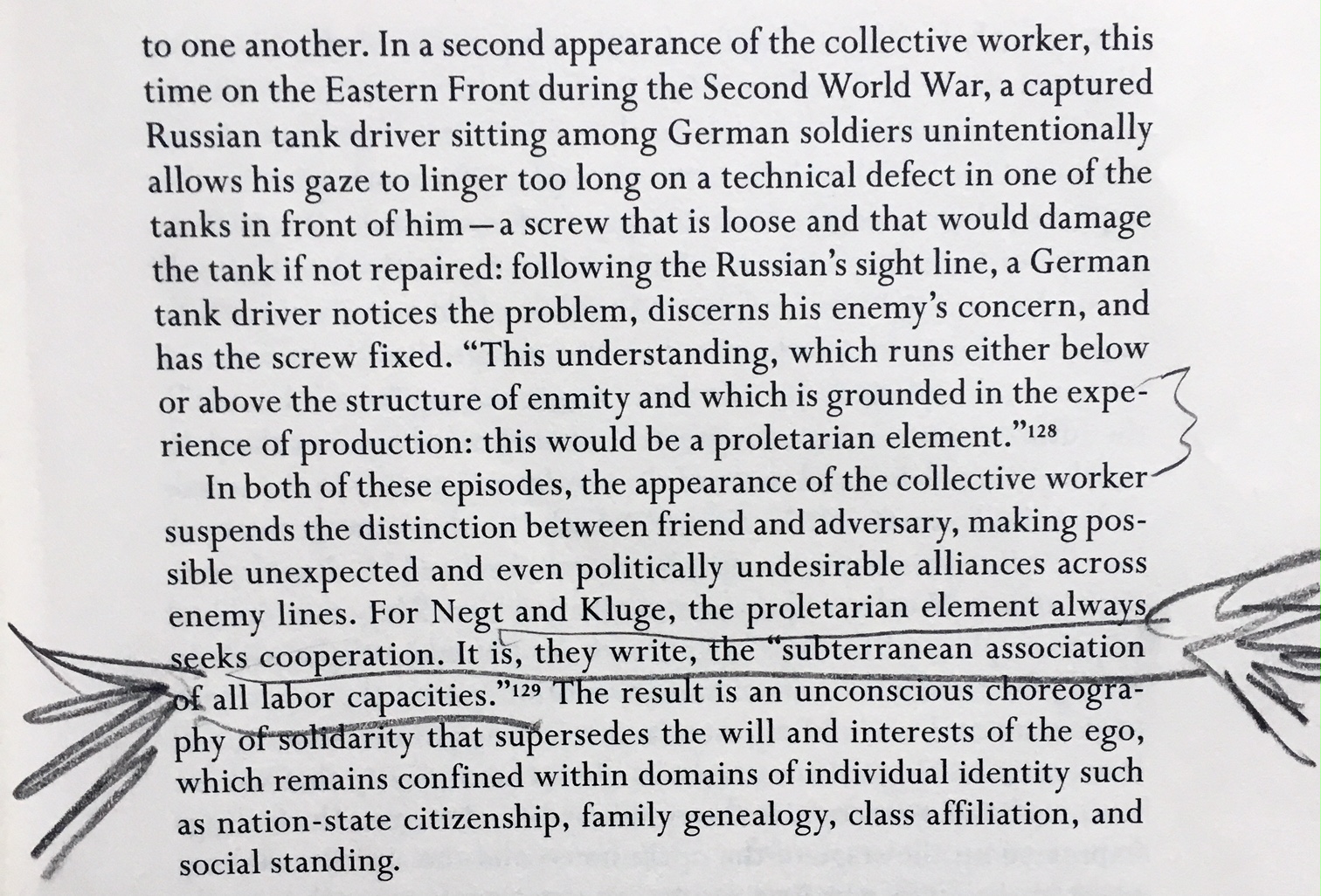

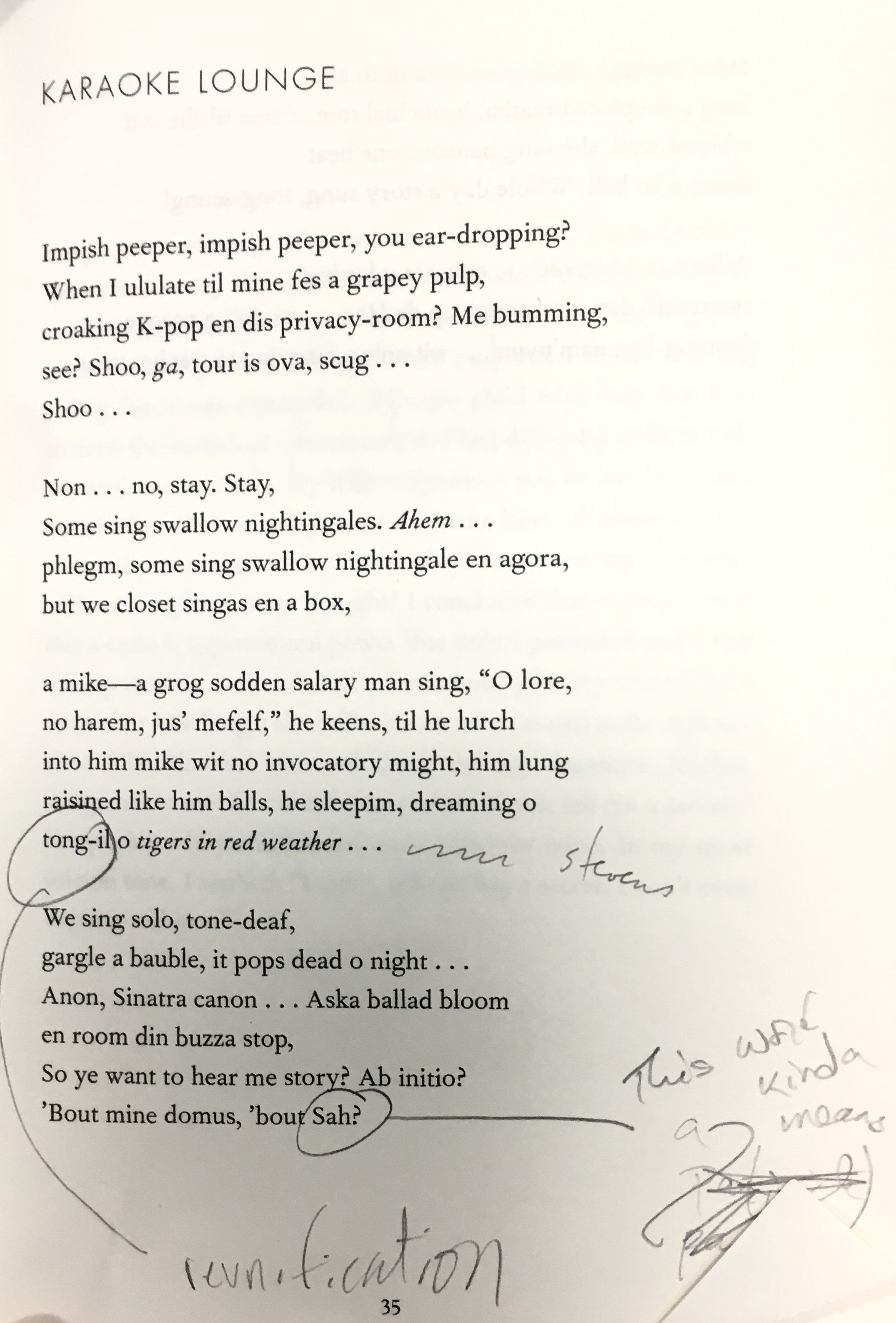

So, for instance, when we looked at Karaoke Lounge,

we learned that “Sah” (which recurs throughout the text as a key name/figure) can have the sense of “history” in compound constructions in Korean. And still more striking, perhaps, that “tong-il” in the line “tong-il o tigers in red weather” means “reunification” — which utterly transforms the Stevensian allusion of the italics, by invoking the specific geopolitics of the Korean peninsula.

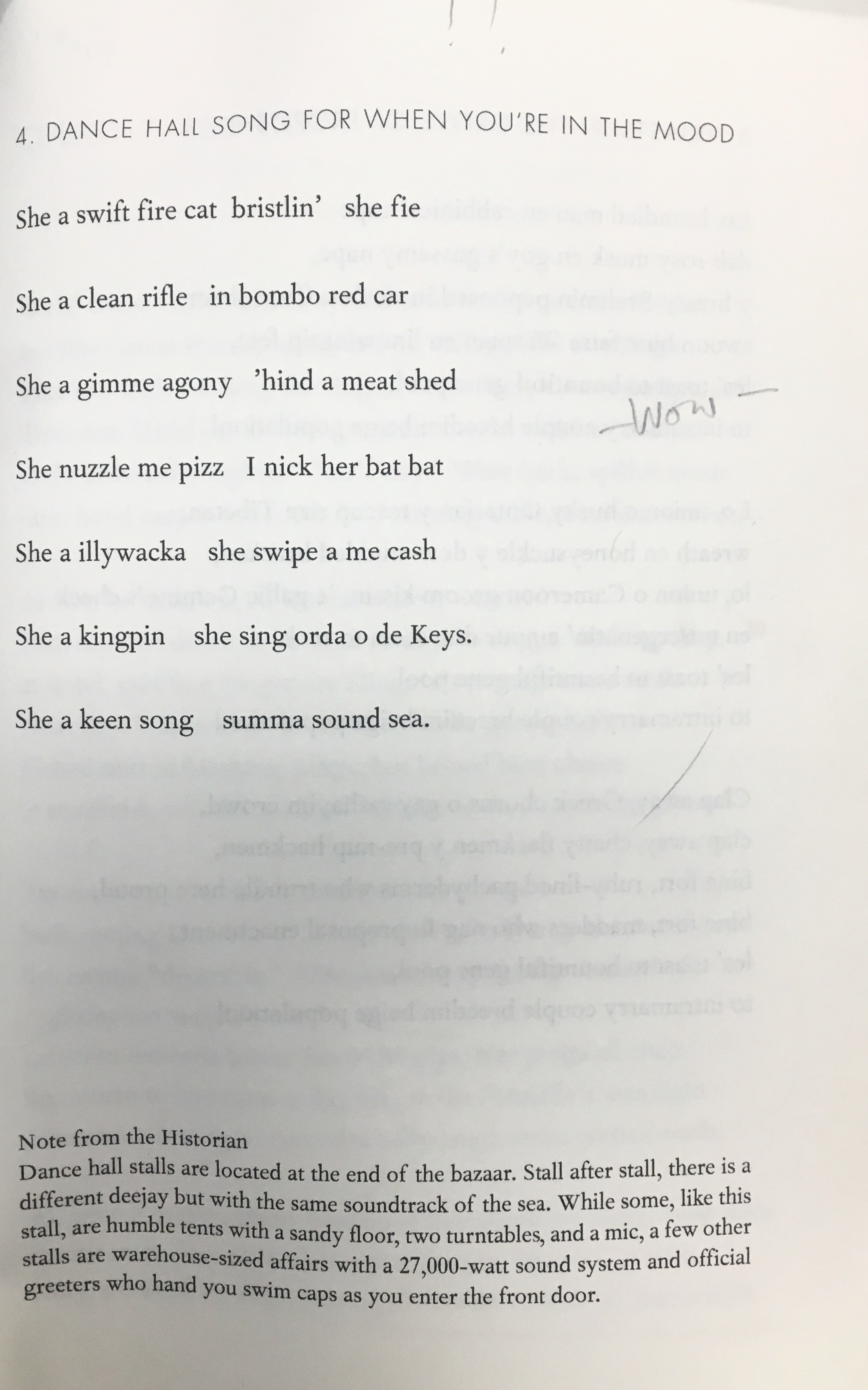

We took a turn into the question of allusion/inter-textuality more generally, moving from the extraordinary use of Stevens throughout the volume. I was hugely affected by “Dance Hall Song for When You’re in the Mood,” which felt to me, in its conclusion, like nothing less than a leering, skid-row epitome of “The Idea of Order at Key West”:

My sense is that this poem genuinely meets, and in its way, supersedes, one of the great poems of the twentieth century: it contains it (in both senses — “has it inside” and also “cordons it off”), and knows more than it did. Amazing.

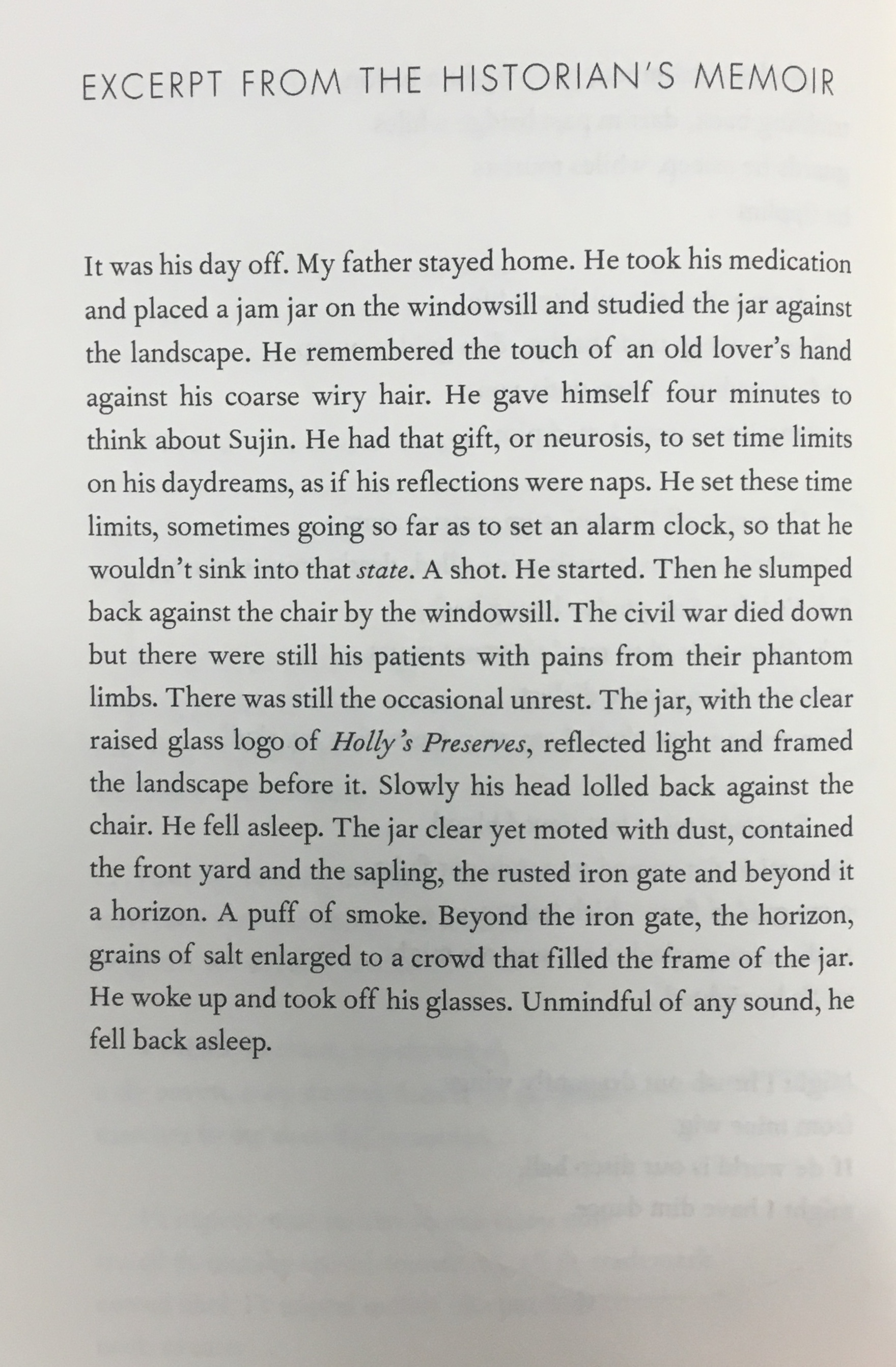

Similarly, the final page of the book, the last “Excerpt from the Historian’s Memoir” displaces and restages the central conceit of Stevens’s “Anecdote of the Jar”:

The juxtaposition of the sleepy exile, sitting on the jittery vista of African civil war (“A shot”; “A puff of smoke”), as that jar (“moted with dust”) made the shattered tropics (almost) stand up…it is nearly too much to bear. Recall that Stevens’s original jar “took dominion everywhere.” Well. Did it? Could we place it on a hill in the Desert? And would it make that slovenly wilderness (Dubai plus Las Vegas plus Disney World plus Janjaweed and Bengali ship-breakers?) come to cognitive/linguistic attention? Cathy Park Hong poses the question in an uncanny way. (Wait, had we even thought of that question? Actually, in a way we sort of had: Dolven and I, quite a few years back, did an event in Brooklyn on Stevens and geography — in which people did indeed take jars out along the Gowanus canal, and set them up in various locations to see what happened…).

Stevens felt to me like the dominant poetic referent throughout Dance Dance Revolution. But we also talked a little about a kind of “absent presence”: Ezra Pound. The poem’s poly-vocality, its roving, choked, perverse fluency — these feel to me essentially Poundian. As some of you will know, one of the touchstone essays in twentieth-century poetics is Marjorie Perloff’s “Pound/Stevens: Whose Era?” (1982). Can we understand Hong to be staging a version of that problem in the way she articulates several Stevensian set-pieces in a roiling, archaic Weltsprache that can be thought of as a twenty-first-century update on the Cantos? (I should maybe say that I am myself interested in restaging that problem in different ways: this is an old project of mine; which is linked to this).

There was more in this conversation. We talked about Keats a fair bit as well, since he is also explicitly invoked a number of times. We also talked about talking, meaning the “mouth-feel” of these poems. One of their powers is that they call-out those who would read them aloud: by vocalizing them, one inevitably surfaces one’s biases (prejudices?), in that one speaks the accent that one imagines is that of the (dreamed, global, trans-historical) underclass. It is interesting and strange to have the work function as a kind of diagnostic test — and in so fraught a domain.

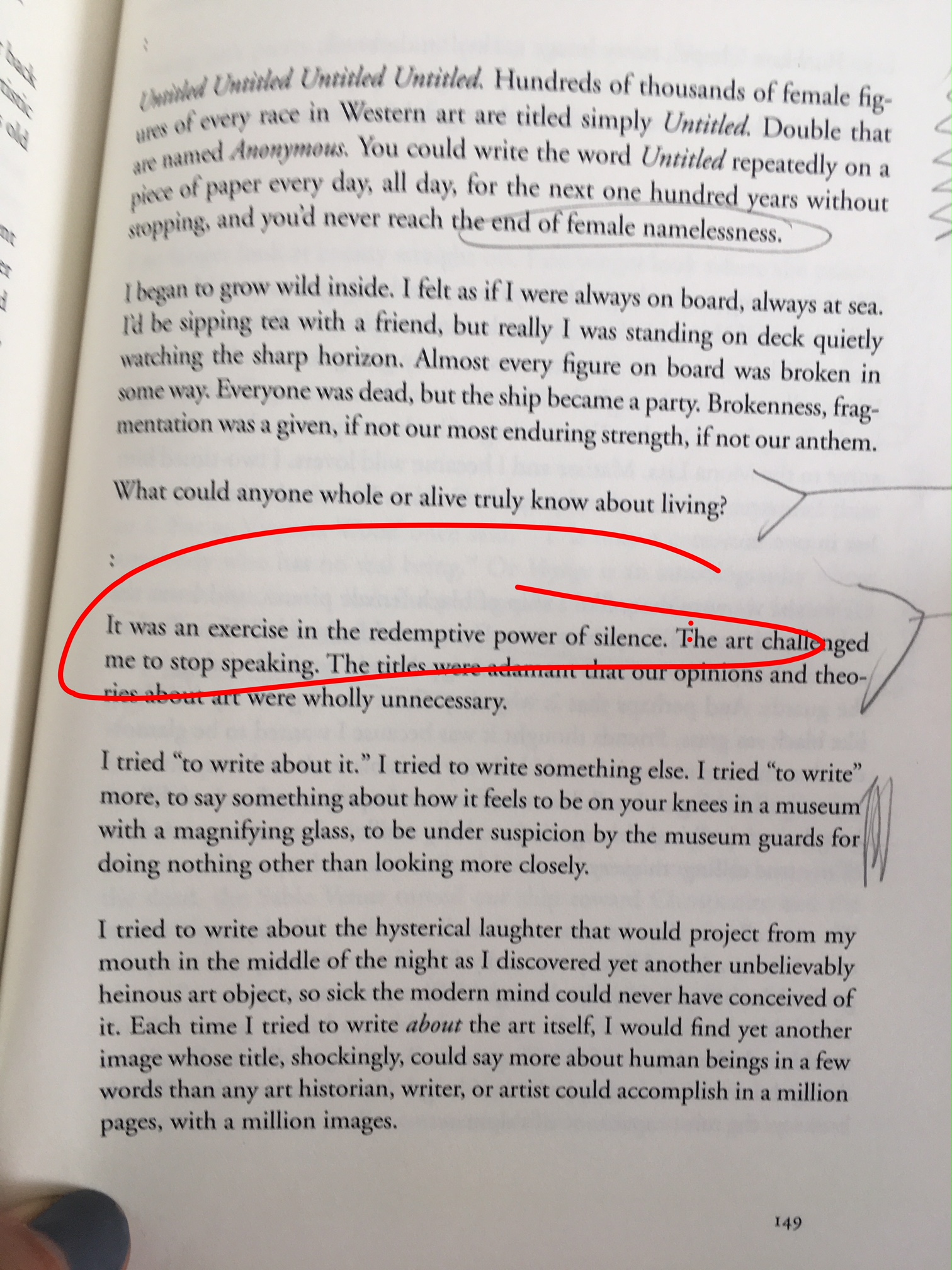

That said, we also noticed that there is something prickly and “resistant” in this book. If I look at my endpaper annotations (where I tried to keep track of our discussion), I see that I wrote; “multiculturalism and capitalism are impossible to pry apart in Hong.” Fair enough. But then I also wrote (here recording, I think, a point that Dolven made): “if you want to parse resistance and complicity (which is so much the sorting reflex of our political moment!) this book will NOT help you. There is no purity fetish here.” And that feels very right. It is this aspect of the book, I think, that gives it an interesting autonomy from some of the currents with which one might initially think it would drift. I am not sure I am here saying anything other than: this is one extraordinarily powerful work of poetics (and history).

*

For me, the closest any of us got to articulating that power came when Dolven reached back to our ongoing conversation about the relationship between a “linguistics” and a “poetics” of history. And what I felt him working to say was that in Dance Dance Revolution one experiences a gradual devaluation of the “code-effects” of language in preference for a kind of “energetics” thereof. It is hard for me now to reconstruct how RIGHT and how POWERFUL this felt at that moment, for me, in our session.

Yes. In that direction lies something. Something with real potential for us as we round out a semester of thinking about poetic form and historical method.

*

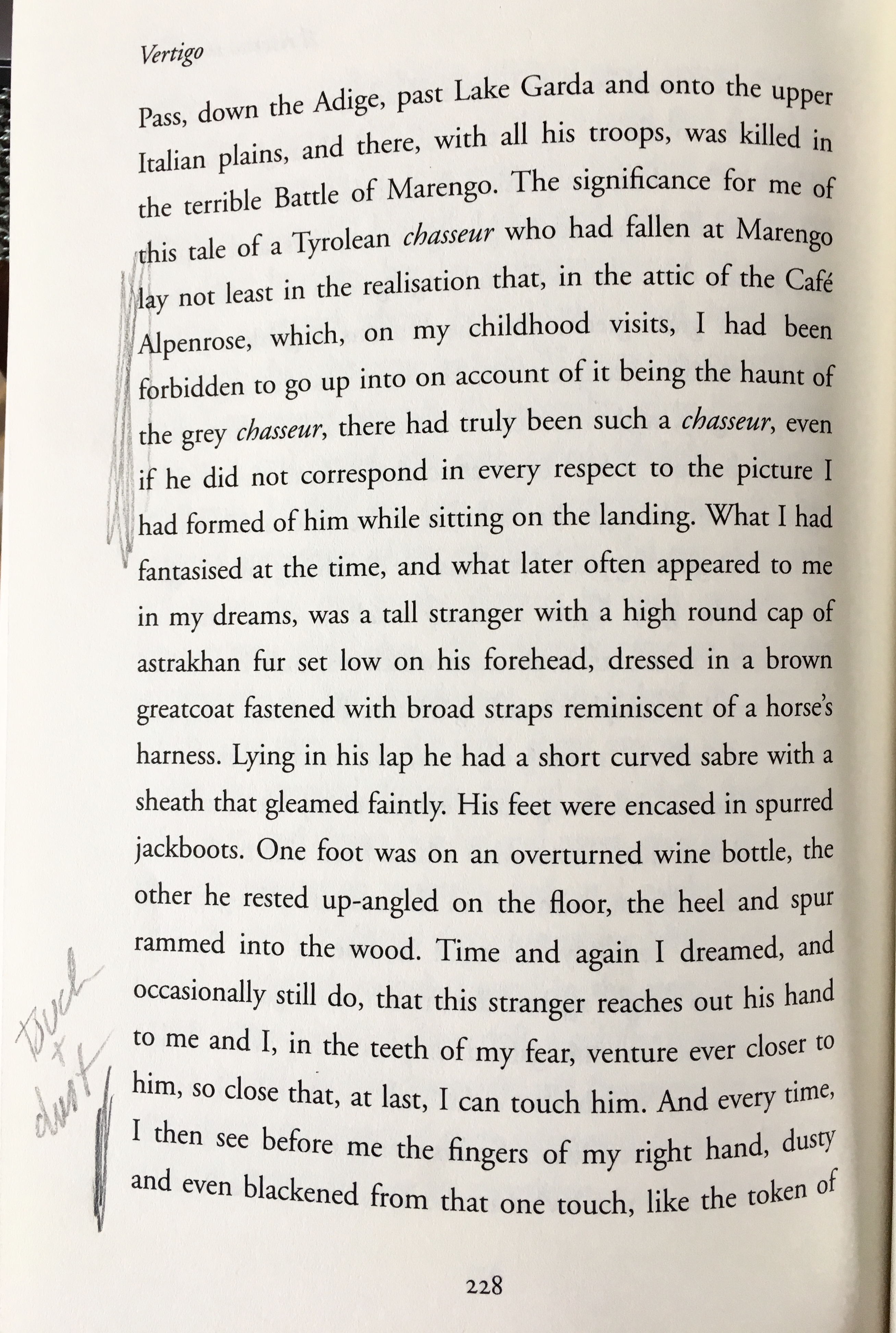

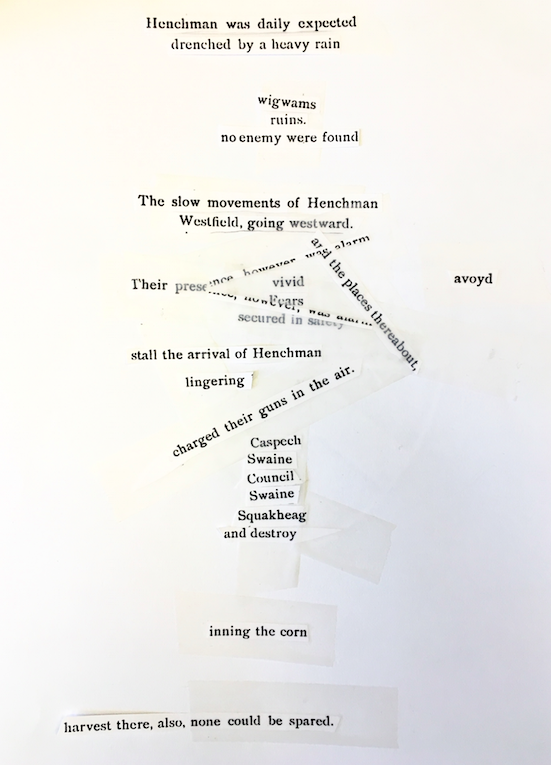

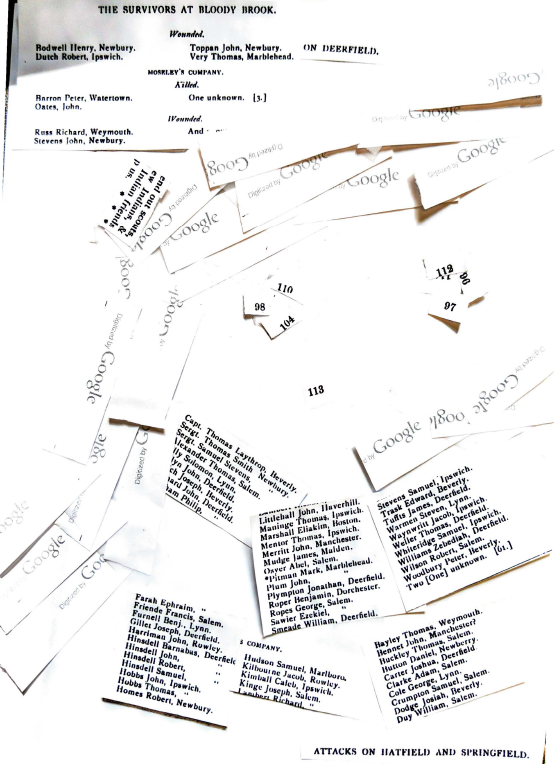

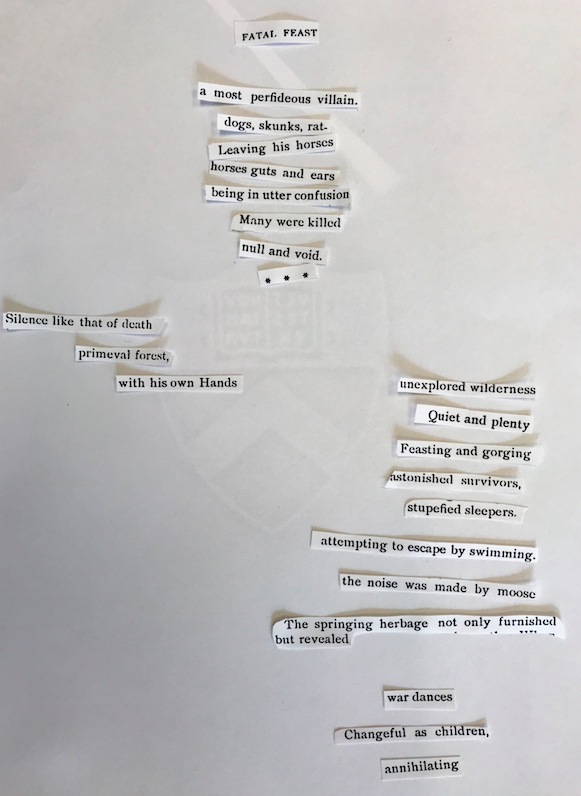

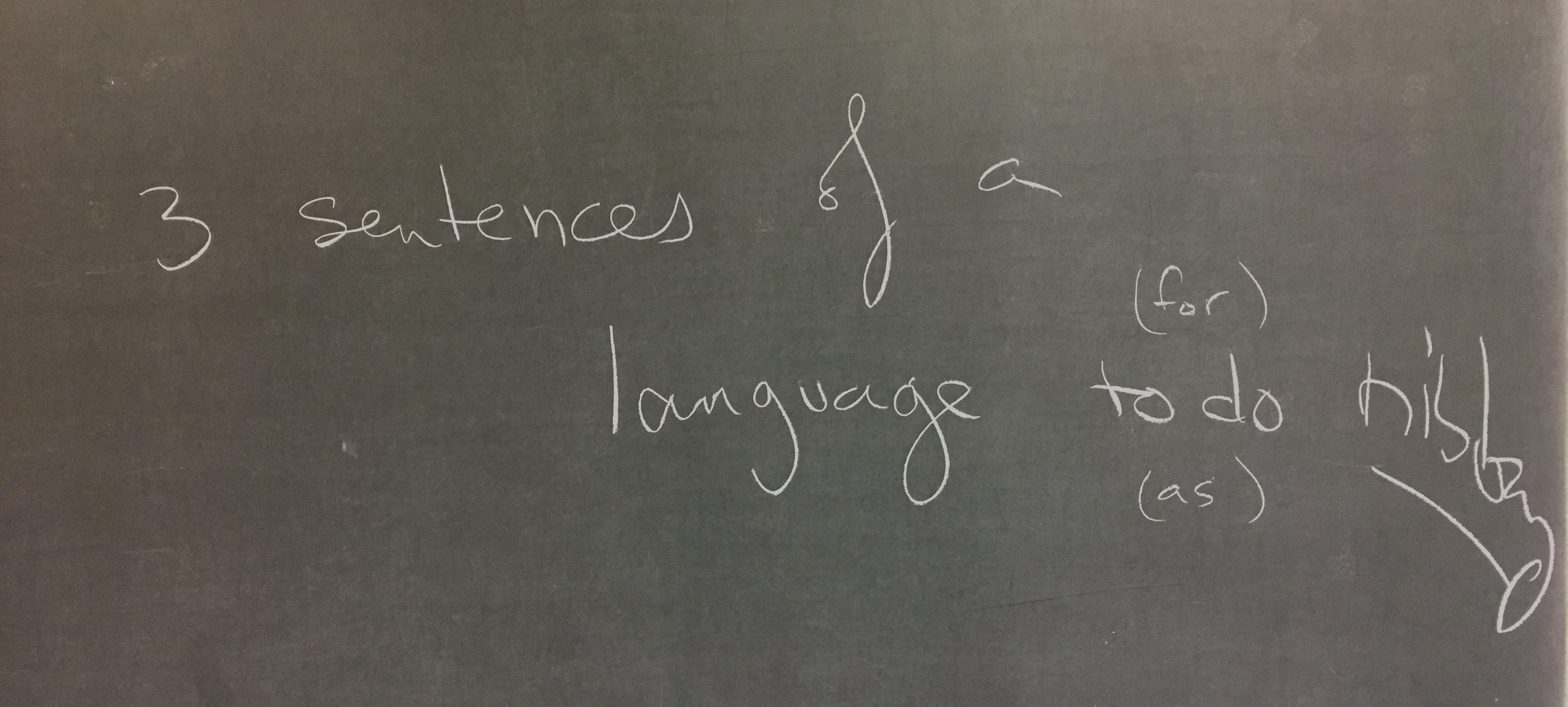

But we weren’t quite done. No. We had break. And an exercise. It looked like this:

Well, it was hard.

I think we all basically failed. Right? I mean, did any of you come up with a new language for history? James smeared his sheet in the grass (reminding me of some of Helen Mirra’s work). Some of you overheard snatches of conversation, and gently allowed the world to become incomprehensible.

Was progress being made? Or were we a pastiche, finally, of ourselves? Something straight out of Don DeLillo?

![]()

I found myself thinking something sort of basic — thinking back to our first session and our “exercises in style” exercises. How little of this we do, as historical and analytic thinkers. When one stops and thinks about it, it is really sort of incredible how infrequently we attend to our essential tools. Nor need we exaggerate what would be involved in stretching our linguistic range. After all, wouldn’t we actually activate a new language for doing history simply by pre-committing to write with, say, no verbs? Or obliging oneself to start every sentence with a proper noun? Or, indeed, via any one of a nearly infinite array of Oulipian constraints and permutations.

A new language for history.

It is too ambitious, of course.

But as I said, as we closed our session, there are moments, I feel, in which a good, honest FAIL — a failure in the course of trying to do something that is important, and simply too hard — is essential. The ratio of time we spend, as elite practitioners of the humanistic enterprise in its academic form, shooting bunnies (basketball expression, meaning very easy shots — “gimmies”), as against the time we spend on stuff that is too hard for us to do…it is a ratio, I would argue, on the order of a thousand-to-one. Maybe even that underestimates it.

So if you spent thirty minutes walking around campus feeling a little hopeless about the possibility of conjuring a new language for doing history equal to the articulation of a historical consciousness for our time (as I did)…well,…

…good?

*

Thank you for an engaging semester.

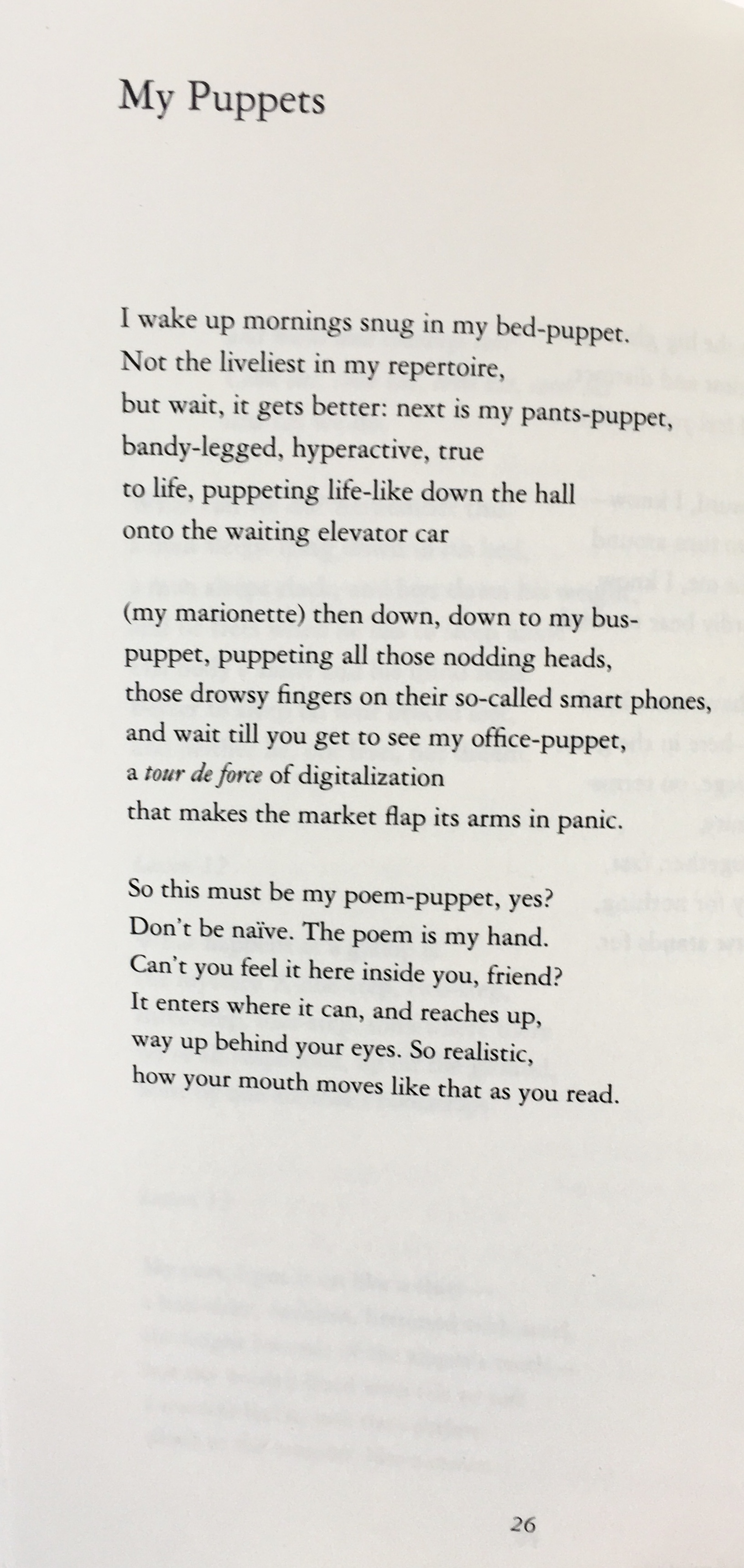

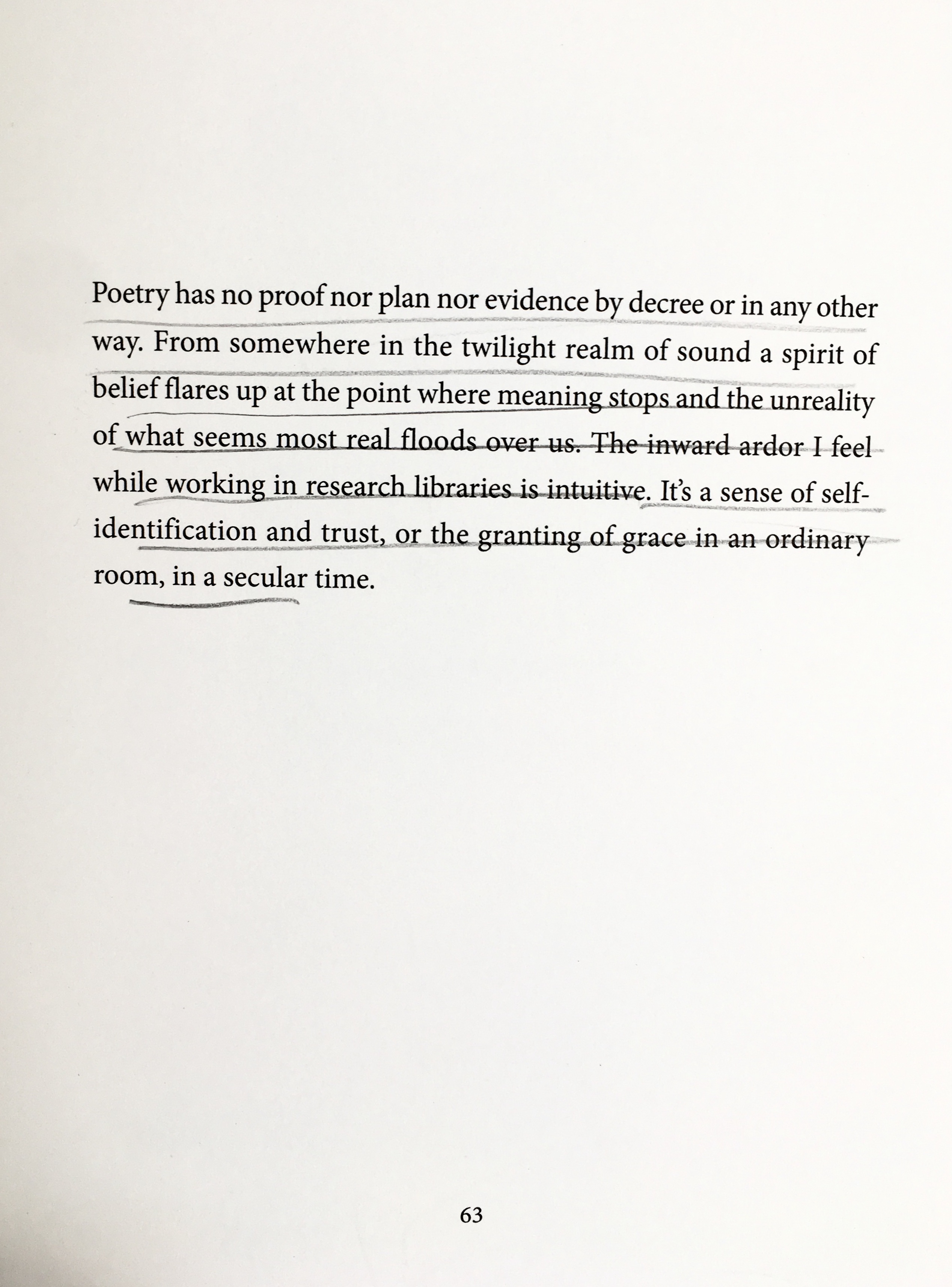

(Oh, and here is my final punctum exercise… Looking forward to reading yours!)

DGB