There are numerous ongoing initiatives and conversations in the archival profession revolving around issues of racial and social justice, and language justice is one of the key components of both. The term “language justice” as defined in the Language Justice Toolkit, “… is about building and sustaining multilingual spaces in our organizations and social movements so that everyone’s voice can be heard both as an individual and as part of a diversity of communities and cultures. Valuing language justice means recognizing the social and political dimensions of language and language access, while working to dismantle language barriers, equalize power dynamics, and build strong communities for social and racial justice.”[1]

As a result, what language is used in our finding aids to describe collections is inherently tied to movements of decolonization, as well as racial and social justice. Princeton University has extensive holdings of Latin American archives, and Spanish is the predominant language of these materials, yet the description in the majority of the legacy finding aids is written in English. It is probably safe to assume that a considerable number of the likely users of these collections would be native Spanish speakers, and some might not even read English. Therefore, why impede the accessibility and navigation of the contents in finding aids by imposing English as the default language? In a 2010 study investigating the usages and expectations of multilingual resources in Chinese digital libraries conducted by Dan Wu, Nanhui Gu, and Daqing He, users had considerably more difficulties searching for information created in a language that they do not understand. Many users in this situation reported having to rely on online translation tools, but in general, were not satisfied with the accuracy of the translations.[2]

By creating finding aids in Spanish, Spanish-speaking researchers can more easily access and navigate archival collections without having to rely exclusively on translation tools. As part of applying language justice concepts to our descriptive practices, patrons should not have to be able to read or find alternative methods of understanding the dominant English language in order to engage with the collections found in our institutions, especially those that may be of direct relevance to themselves and their communities. As Dorothy Berry writes, “Our descriptive systems are often the first interaction patrons have with our institutions, and when the language and systems feel alienating, patrons will take what they need and leave the rest… The question of who will come visit is rarely asked of the house we have built and whether or not our door has ever been truly open in the first place.”[3]

The growing interest in inclusive description efforts with the intent of being more respectful of the communities and the people that are impacted by our descriptive work should also be directed towards the language we use in our finding aids. It is not only the right thing to do, but will also lead to building trust and engagement with communities that we are supposedly trying to serve. As Xaviera Flores and Elizabeth Dunham note in their article on bilingual finding aids, “Spanish-language finding aids have proven to be valuable tools for building community relationships and further developing the Chicano/a Research Collection. The Collection’s curator and curator emerita both report encountering members of the Mexican American community who feel that Spanish finding aids show an appreciation and respect of the language and culture that is often lacking in their dealings with Anglo society.”[4]

At Princeton University Library, my predecessor, Elvia Arroyo-Ramírez, began creating some bilingual finding aids, wherein collection- and series- level descriptions were written in English, but folder titles and more detailed file-level scope and content notes were written in Spanish, as seen in the finding aid for the Idea Vilariño Papers.

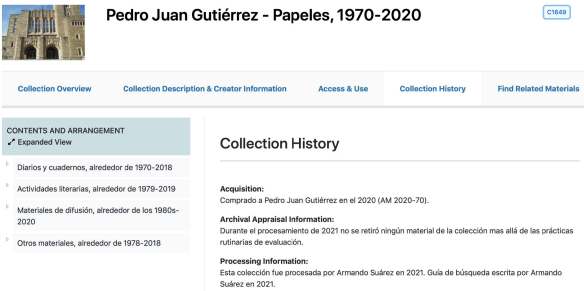

Subsequently, a few months after my hiring, the Inclusive Description Working Group [5] was formed in May 2019, composed of a group of archivists committed to tackling the complex issue of cultural sensitivity in archival description, and to critically rethinking our role as archivists in order to create description that is respectful to the individuals and communities who create, use, and are represented in the archival collections we manage. One issue that the group began to discuss is which language to use when writing finding aids for archival collections in which most of the materials are not in English. As a result of these discussions, we are now writing finding aids in Spanish for predominantly Spanish-language collections, as seen in the screenshots below for the collections of Jorge Díaz and Pedro Juan Gutiérrez respectively.

Language is a carrier of culture and communication[6] and forms an integral part of one’s identity. Reading and speaking in one’s native language provides a sense of connection to one’s culture, community, and self. Therefore, as we move forward at Princeton University Library, we will continue to work to ensure that newly-processed, predominantly Spanish-language collections have corresponding finding aids written in Spanish. With our recent migration to ArchivesSpace, we also launched a new finding aid discovery site. As we continue to make improvements to these platforms, we will look for ways to enrich and facilitate the experience of the researchers using our finding aids, such as the inclusion of field labels in Spanish. Moreover, future work will hopefully include the application of technologies that could enable multilingual capabilities in our finding aid platform in order to facilitate navigation for different communities of users researching in our collections. Furthermore, we would at some point like to address legacy finding aids for the Latin American collections in order to rewrite the description in Spanish.

If we are truly committed to issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion in archives and libraries, creating multilingual spaces in our institutions and organizations must form part of those initiatives. As noted in the language justice how-to-guide provided by Antena Aire,[7] “…strategies for bridging the divides of language are essential to any endeavor that truly seeks to be inclusive of people from different cultures, different backgrounds, and different perspectives.”[8] By providing finding aids with description that matches the predominant language of the materials, we are respecting the right that everyone has to communicate in the language in which they feel most comfortable.

Notes

[1] Communities Creating Healthy Environments (CCHE). CCHE Language Justice Toolkit.https://nesfp.org/sites/default/files/resources/language_justice_toolkit.pdf.

[2] Wu, Dan, Nanhui Gu, and Daqing He. “The Usages and Expectations of Multilingual Information Access in Chinese Academic Digital Libraries,” 2010.

[3] Berry, Dorothy. “The House Archives Built.” up//root, June 22, 2021. https://www.uproot.space/features/the-house-archives-built

[4] Dunham, Elizabeth, and Xaviera Flores. “Breaking the Language Barrier: Describing Chicano Archives with Bilingual Finding Aids.” The American Archivist 77 (2), 2014: 499–509. doi:10.17723/aarc.77.2.p66l555g15g981p6.

[5] Suárez, Armando. “ Inclusive Description Working Group.” This Side of Metadata, February 28, 2020. https://blogs.princeton.edu/techsvs/2020/02/28/inclusive-description-working-group/

[6] Sutherland, Tonia, and Alyssa Purcell. “A Weapon and a Tool: Decolonizing Description and Embracing Redescription as Liberatory Archival Praxis.” The International Journal of Information, Diversity, & Inclusion 5 (1), 2021. doi:10.33137/ijidi.v5i1.34669.

[7] “Antena Aire (formerly called Antena) was a language justice and language experimentation collaborative by Jen/Eleana Hofer and JD Pluecker, both of whom are writers, artists, literary translators, bookmakers and activist interpreters. From 2010-2020, Antena Aire used on-the-ground practices building equitable communication as a generative strategies for making artistic works.” http://antenaantena.org

[8] “How to Build Language Justice.” Antena Aire. http://antenaantena.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/AntenaAire_HowToBuildLanguageJustice-2020.pdf