“By Dawn’s Early Light”: Loans from the Leonard L. Milberg ’53 Collection of Jewish-American Writers on display at the Center for Jewish History in New York

❧ “By Dawn’s Early Light: : An exhibition of more than 140 books, maps, prints, manuscripts, and paintings documenting Jewish contributions to American culture from the nation’s founding to the Civil War, opening on March 16 at the Center for Jewish History. On display are many items from the Library’s Leonard L. Milberg ‘53 Collection of Jewish-American Writers as well as loans from the Library Company of Philadelphia, the American Jewish Historical Society, and Mr. Milberg’s personal collection.

“For Jews, initially a tiny minority in the early Republic, freedom was both liberating and confounding. As individuals they were free to participate as full citizens in the hurly-burly of the new nation’s political and social life. But as members of a group that sought to remain distinctive, freedom was daunting. In response to the challenges of liberty, Jews adopted and adapted American cultural idioms to express themselves in new ways, as Americans and as Jews. In the process, they invented American Jewish culture.” (Exhibition handout, p.1)

This exhibition was made possible through the generosity of Leonard L. Milberg with additional support from the Center for Jewish History.

For further publicity see:

• Announcement from the Library Company of Philadelphia [link]

• Article published in The Jewish Voice [link]

Editions of the ‘Columbus Letter’ : Scans newly provided by the Library

❧ Columbus’s description of his first voyage first appeared in print in a Spanish edition published in Barcelona in 1493. Within four years it had gone through fifteen known editions, including seven Latin editions, one German edition, a paraphrase in Italian verse in five editions, and a second Spanish edition, Valladolid, about 1497. These fifteen different editions were products of presses scattered in ten cities across Europe.

❧ Of these fifteen editions, there is at Princeton an exemplar for three of the seven Latin editions and an exemplar of the German edition. The most direct manner of listing these is the number assigned in F.R. Goff, Incunabula in American Libraries (1964):

• C-758. Latin. [Rome: Stephan Plannck, after 29 April 1493]. Cyrus McCormick copy, presented to PUL. Permanent Link:

http://arks.princeton.edu/ark:/88435/sq87bv90x

• C-759. Latin. Rome: Eucharius Silber, [after 29 April] 1493. Grenville Kane copy, acquired by PUL. Permanent Link:

http://arks.princeton.edu/ark:/88435/xp68kh56z and the Scheide Library copy.

Permanent Link: http://arks.princeton.edu/ark:/88435/sx61dn657

• V-125. Latin. [Basel:] I.B. [Johann Bergmann, de Olpe] 1494. Grenville Kane copy, acquired by PUL. Permanent Link:

http://arks.princeton.edu/ark:/88435/j9602191d

• C-762. German. Strassburg: Bartholomaeus Kistler, 30 Sept. 1497. Grenville Kane copy, acquired by PUL. Permanent Link:

http://arks.princeton.edu/ark:/88435/nz806098g

❧ REFERENCE: W. Eames, “Columbus’ Letter on the Discovery of America (1493-1497)” in the Bulletin of the New York Public Library, 1924, 28:597-599. (NB: Eames lists seventeen editions; however, the number is actually fifteen because Eames was unaware that three issued by Marchant in Paris were variants of one edition.)

Digital collections extended

Recently the Library completed work extending the holdings of two digital collections

❧ The Sid Lapidus ’59 Collection on Liberty and the American Revolution • Eighty-five new digitial books added on the topics of slavery and the slave trade in the empires of Great Britain and France. The books are part of his large private collection and Mr. Lapidus generously made them available for scanning. To see these additional books, go to http://goo.gl/Cuix5H

❧ Annotated Books • The PUDL’s digitization of annotated printed books in Firestone Library continues, with the addition of seven additional titles, including Gabriel Harvey’s annotated copies of Machiavelli’s Arte of Warre; Buchanan’s De Maria Scotorum regina and his Detectioun of the duinges of Marie Quene of Scottes; Smith’s De recta & emendata linguæ Anglicæ scriptione, dialogus; Freigius’s Paratitla … juris civilis; Magnus Olaus’s Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus; and Melanchthon’s Selectarum declamationum.

Celebrating the Presidency of Princeton

The retirement of Shirley Tilghman as the19th President of Princeton University at the end of June 2013 provided an opportunity for the Friends of the Princeton University Library to celebrate the presidency of the University by making a gift to the Library in her honor. The Special Collections curators presented a wide range of possibilities to identify a suitable purchase. The choice: one of the extremely rare books that can be documented as having belonged to Jonathan Dickinson (1688-1747), the first President of the College of New Jersey.

At its modest beginning in 1746 in Dickinson’s parsonage in Elizabeth, the college consisted of the president, one tutor, and eight or ten students. Dickinson’s books were the college library. Tactica Sacra (Sacred Strategies), by John Arrowsmith, Puritan divine of Trinity College, Cambridge, is a manual for the spiritual warrior, part of the armament of clergyman Dickinson. A large quarto of 400 pages in its original 17th-century full calf binding, the book carries an inscription on its title page in Dickinson’s hand: “Jonathan Dickinson’s Book… .” The group of Friends who supported the acquisition are named on a bookplate added to the volume.

The University’s efforts to acquire books with a Princeton association started in earnest during the second half the 19th century. The extant books belonging to Jonathan Edwards were added, as well as some from other early presidents, including Samuel Finley. John Witherspoon’s books had been acquired in the first part of the 19th century due to the efforts of his son-in-law Samuel Stanhope Smith. These volumes were purchased not so much because they had belonged to Witherspoon but because, after the Nassau Hall fire of 1802, the college needed books. Recognition of the associational value of the Witherspoon books came to a climax during the librarianship of Julian Boyd. In the early 1940s Boyd instructed rare book librarian Julie Hudson to reassemble the Witherspoon library, which had been dispersed throughout the collections. The earliest survivors of the college library are on view in the Eighteenth-Century Room, just inside the entrance to the Main Exhibition Gallery in Firestone Library.

Tactica Sacra is the Library’s first book from Dickinson’s library with his statement of ownership. Given some years ago was a copy of Poole’s Annotations (2 vols.; London, 1683-1685), which has a record of Dickinson’s family and offspring in his hand on the verso of the last leaf of Malachi. However, these volumes lack the title pages, which presumably would have carried his signature and marking that the Poole was “his book.”

In addition to the Dickinson inscription, a hitherto unknown early American book label, “Samuelis Melyen liber,” is fixed to the front pastedown. The Reverend Samuel Melyen was the first minister of the nascent congregations in Elizabeth and environs. Jonathan Dickinson married Melyen’s sister Joanna in 1709, around the time that he began his ministerial work in the Elizabeth Town parish. Melyen died ca. 1711, and Dickinson emerged as the leading minister, a post he held until his death in 1747. Samuel Melyen was clearly the first owner of this book. Dickinson’s inscription in full states that it was a gift of one Mr. Tilley: “Jonathan Dickinson’s Book Ex dono D. Tilley.” The Tilley family and the Melyen family were related by marriage, but the precise identity of “D[ominus (i.e. Mister)]. Tilley” is not yet known. Dickinson apparently owned another book in which he inscribed “Jonathan Dickinson’s Book Ex dono D. Tilley.” It is a copy of Samuel Cradock, The Harmony of the Four Evangelists (London, 1668). The present whereabouts of this copy are unknown; it was last recorded in 1896. Further, recently come to light is a comparably inscribed book held at the Hougton Library: a London, 1688 edition of the Psalms [Details] [Image].

The Princeton association of the Tactica Sacra does not stop with Dickinson. Beneath Dickinson’s inscription is the following: “Jonathan Elmer His Book 1768.” Elmer (Yale 1747) was pastor at New Providence, New Jersey, from 1750 onward. A slip in the book states that after Jonathan Elmer it was owned by Philemon Elmer (1752-1827); then his daughter Catharine, who married Aaron Coe, Princeton 1797 (d. 1857); then by their son the Reverend Philemon Elmer Coe (Princeton 1834); then his sister Catherine Elmer Coe, who married Alfred Mills (Yale 1847); then by their children Edith, Alfred Elmer Mills (Princeton 1882), and Edward K. Mills (Princeton 1896).

Update regarding Princeton’s copy of Le Miroir des événemens actuels

Heinrich Glarean (1488-1563) and his Chronologia of the Ancient World

Anthony Grafton and Urs B. Leu have completed two studies of Princeton’s copy of the Chronologia:

Published in August: “Chronologia est unica historiae lux: how Glarean studied and taught the chronology of the ancient world” in Heinrich Glarean’s Books: The Intellectual World of a Sixteenth-Century Musical Humanist edited by Iain Fenlon and Inga Mai Groote (Cambridge University Press, 2013). See: http://www.cambridge.org/asia/catalogue/catalogue.asp?isbn=9781107022690

Forthcoming: Henricus Glareanus’s (1488-1563) Chronologia of the Ancient World. A Facsimile Edition of a Heavily Annotated Copy Held in Princeton University Library (Leiden: Brill). See: http://www.brill.com/products/book/henricus-glareanuss-1488-1563-chronologia-ancient-world

A full scan of this notable annotated humanistic book is available in the Princeton University Digital Library. See: http://arks.princeton.edu/ark:/88435/s1784k81w

The Art of Factual Writing • An Exhibition in Tribute to John McPhee ’53

Currently on view in the lobby of Firestone Library through Commencement.

The Princeton University Library and the Class of 1953 join in honoring the author John McPhee on the occasion of his 60th class reunion. McPhee has been a Ferris Professor of Journalism at Princeton since 1974, leading two seminars every three years. The present exhibition focuses on McPhee’s approach to factual writing, which is central to his teaching at Princeton and has contributed to the success of his many students. The exhibition shows stages of the creative process, from concept to bound book and beyond. McPhee’s own papers show the author at work, beginning with information gathering in the field and formalizing his notes. McPhee structures his writing with the help of diagrams, as explained in his recent article, “Structures,” in The New Yorker (January 14, 2013). Then, working with editors and publishers, he crafts a series of manuscript drafts and corrects proofs. The resulting articles, first published in The New Yorker and, occasionally, other magazines, have been the starting point for most of McPhee’s twentyeight books and two readers published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, as well as reprints, e-books, and translations. Included in the exhibition are loans from Farrar, Straus and Giroux and The New Yorker, as well as papers and awards loaned by the author himself.

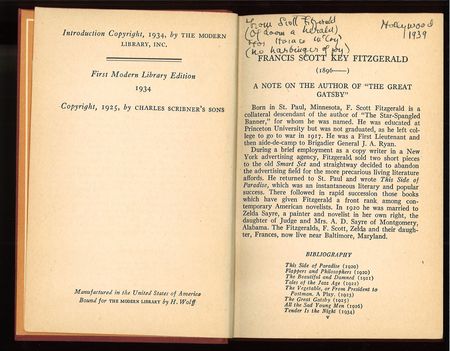

Authorship of The Great Gatsby epigraph revealed • Hollywood, 1939

Like the novel itself, the epigraph of The Great Gatsby has achieved mythic status.

Then wear the gold hat, if that will move her;

If you can bounce high, bounce for her too,

Till she cry “Lover, gold-hatted, high-bouncing lover,

I must have you!”

– Thomas Parke D’Invilliers

Who was Thomas Parke D’Invilliers? First appearing in This Side of Paradise, he is the poet-companion of Amory Blaine and carried the epithet “that awful highbrow.” Here, on the title page of Fitzgerald’s third novel, D’Invilliers provides paratextual poetry. Custom expects real authors to provide epigraphs. His signed epigraph reverses what we understood him to be when we first met him.

According to the general editor of the Cambridge Fitzgerald Edition, Professor James L.W. West III

“… several times during his life, F. Scott Fitzgerald received queries from people who wanted to quote that epigraph. They wanted to know who T. P. D’Invilliers was, so they could seek permission. But I have never seen, am not aware of, any document in which Fitzgerald says that T.P. D’Invilliers is a fictional character, and that he wrote that epigraph himself.”

A recent gift of a presentation copy of The Great Gatsby provides documentary evidence of what has long been assumed regarding Fitzgerald’s authorship of the epigraph. Moreover, this copy has an added attraction. The presentation inscription is the autograph original of a Fitzgerald poem.

“From Scott Fitzgerald / (Of doom a herald) / To Horace McCoy / (no harbinger of joy)

Hollywood 1939”

Horace McCoy was a novelist and near contemporary of Fitzgerald. McCoy is best known for his novel They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (1935).

The gift is a legacy to the Library from the Lawrence D. Stewart Living Trust. Prof. Stewart purchased the book in an California bookstore and published his findings in 1957 —- Lawrence D. Stewart, “Scott Fitzgerald D’Invilliers,” American Literature, XXIX (May 1957), 212-213. [Stable URL http://www.jstor.org/stable/2922109.] His article did not reproduce the signed title page nor the autograph presentation.

To Have Friends Come from Afar–Isn’t That a Joy? • A Post about some Chinese holdings in the Scheide Library

A Brief Essay by Minjie Chen (陈敏捷)

Wrapped in paper and tucked in the protective case of Tong Jian Zong Lei (通鉴总类), a Chinese history book, were four aging black-and-white photographs. With frayed edges and small stained spots, the pictures have nonetheless retained their sharpness, allowing us to see what a skilled photographer had captured through his curious lens one century ago in the hometown of Confucius. Fading handwriting on the back of each photo provided precious clues to their content and provenance.

The history book, compiled by SHEN Shu of the Song Dynasty (960-1279) and printed in 1363 during the late Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), is part of the private Scheide Library collection housed in Firestone Library at Princeton University. The photos, according to notes on the back, were taken by a physician named Charles H. Lyon and presented to John Hinsdale Scheide (1875-1942, Princeton class of 1896) by Mrs. Lyon in January 1937.

The first photo is a portrait of a round-faced Chinese man in the official robe and headwear of the Qing Dynasty. If the ink note scratched on the back, “a descendant of Confucius,” is reliable, the subject of the photo is KONG Lingyi (孔令贻, 1872-1919). As a seventy-sixth generation descendant of Confucius in the male line of descent, Kong inherited the title “Duke Confucius” (衍圣公) from his father at age five. The note also indicates that Dr. Lyon, the photographer, is the “physician to the subject.” It is unclear how often Kong had sought Dr. Lyon’s medical expertise, but interacting with Westerners from afar and posing for photographs would not have been out of place for Duke Kong. European ambassadors and colonial administrators had paid visits to the Confucius Temple in Qufu (曲阜), Shandong Province, and had photos taken with the Duke, who lived in the Kong family mansion adjacent to the temple complex, as generations of the sage’s offspring had done. In a photo held at the National Archives in London, a slightly younger-looking Kong is seen with Reginald Johnston (1874-1938), a Scottish colonial officer who had escorted a portrait of King Edward VII to Confucius’s hometown (and who later became famous for having tutored China’s last emperor, Puyi).

What is remarkable about the portrait taken by Dr. Lyon is that it is a half-body shot of the Duke. During the late Qing dynasty, when cameras were still a novelty to the Chinese, it was taboo to photograph less than a full-body shot of a person, because it was deemed bad luck to have the subject missing arms, legs, or other body parts in photos. Was Kong informed of the outcome of his photo, and was he comfortable about it? As a physician, did Dr. Lyon hold any power of persuasion over Kong, assuring him of the harmlessness of a partial-body picture? At any rate, Lyon’s photograph offers a rare close-up view of the second-to-last Duke Confucius in Chinese history.

Three other photos were taken in and outside the Confucius Temple, where ritual ceremonies were performed every year to worship the sage. Photo no. 2 shows an arch named Que li (阙里), which stood outside the east wall of the temple. Confucius was believed to have started his teaching career in this neighborhood, hence the location of the temple. Photo no. 3 is a front view of the statue of Confucius in Da cheng dian (大成殿, meaning “the Hall of Great Achievements”), which was the architectural center of the temple complex. The statue was inaugurated in 1730 (the eighth year in the reign of Emperor Yongzheng), replacing an earlier one destroyed in a fire in 1724. The fourth photo focuses on the porch of the hall, which is guarded by limestone pillars carved with dragons riding clouds.

Lyon would never know that he had captured the image of vanishing cultural relics. In 1966, twenty years after Lyon died at age 72 in Phillipsburg, New Jersey, the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution broke out in China, followed closely by the “Destruction of Four Olds” campaign. Confucius’s legacy was a prime target among the “old ideas, old culture, old customs, and old habits” to be condemned and eradicated from Chinese society, ostensibly to make room for a brand new world. Hundreds of Red Guards swept into the temple, mansion, and cemetery of Confucius in November 1966, smashing up statues, stone tablets, monuments, and numerous other antiquities. The tombs of Confucius and KONG Lingyi, who died in 1919—one year after Dr. Lyon left China—were both leveled. The Hall of Great Achievements was stripped of statues of Confucius and sixteen of his most famed followers, except for a broken head left among the ruins. The Internet is not short of violent images showing Red Guards in fervent action in Qufu. Online photos revealed that, before being reduced to debris, the 236-year-old statue of Confucius had been disfigured and disgraced by the “revolutionists” who had plastered strips of paper with blasphemous slogans all over it.

With the same determined pursuit for visual clarity with which he had taken Duke Kong’s portrait, Lyon had positioned his lens straight in front of the sage’s statue, taking in the exquisite latticed boards and a pair of lively-looking dragons about to untangle their bodies from the columns. Lyon’s photo is not the only one of the Confucius statue that was no more. However, compared with what we have found in print and digitized resources, his shot is clearly the one that best allows us a belated gaze into the (now ruined) entire shrine from a satisfactory angle.

MAO Zedong’s death in 1976 brought about the end of the Cultural Revolution. In spring 1983, barely five years after DENG Xiaoping had assumed leadership of China and introduced reforms, the government allocated 480,000 RMB (roughly equivalent to 560,000 USD today) for restoring all seventeen statues in the Hall of Great Achievements. Striving for faithful replication in shape, size, and detail, sculptors started their extensive preparation work by collecting information from written records, images, videos, and oral interviews with local residents. (Regretfully, the project team was not aware of Lyon’s superb shot.)

According to the restoration team, the only deliberate point of departure from the original statue was the sage’s facial expression. Launched in 1984, the new statue of Confucius gently smiles down at his worshippers. Local residents were reportedly happy with the reinstated, amicable-looking Confucius, commenting that they used to find his old statue “really scary” (Gong and Wang 62). Such a hearty welcome almost made the silver lining of the massive loss from the “Four Olds” campaign. However, with the aid of Lyon’s photo record, might the jury still be out on whether the old statue truly presented a forbidding expression?

We do not know much about Dr. Lyon and his family or about the couple’s relationship with John H. Scheide. Lyon was born in China to a missionary family possibly from Wooster, Ohio. He graduated with an M.D. degree from the University of Pennsylvania in 1898, and, as a member of the Student Volunteer Movement for Foreign Missions, went to the Philippine Islands in 1900. By 1902 he had become a medical missionary in Jining (济宁), Shandong Province, working as the chief physician of the Rose Bachman Memorial Hospital for Men, which was operated by the Board of Foreign Missions of the Presbyterian Church in the USA. More than a century later, that hospital, now called the Jining First People’s Hospital, is still in business (and accepting patients of both genders). Lyon married Edna P. van Schoick in Shanghai on Dec. 19, 1902. The two met when Lyon visited Edna’s father, Dr. Isaac Lanning van Schoick, who had returned from a mission in China to his home in Hightstown, New Jersey (“Going to China” 9). Indeed, one of the places in which Dr. Van Schoick had been stationed was Jining, to which Edna was perhaps no stranger.

Lyon’s hospital was approximately 35 miles west of Qufu, the birthplace of Confucius. An excursion to Qufu on the back of a horse or donkey along the rural mud road could take several uncomfortable hours, longer if by sedan chair. With a healthy dose of curiosity and determination and the cool-headedness of a physician, Lyon helped preserve the image of what would be demolished by unprecedented political fervor.

One might question the appropriateness of a missionary visiting the temple of Confucius, who, after all, had been treated as a demigod in China. At a formal level, Western missionaries had studied the compatibility and divergence of Confucianism and Christianity, seeking understandings that would, they hoped, aid their evangelical work with the Chinese. On a personal level, anecdotal stories and individual cases suggest that missionaries might have considered the philosophy of Confucius with varying degrees of open-mindedness. Some may even have been influenced by long-term exposure to the ideas of the very people whom they had traveled across the ocean to convert. An especially “quirky” missionary of such a kind can be found in the film The Keys of the Kingdom (1944). Father Francis Chisholm (played by Gregory Peck) returns to his Scottish hometown church after having served the greater half of his life in China. He is heard giving sermons like “The good Christian is a good man, but I have found that the Confucianist usually has a better sense of humor.”

The digitized photos and their catalog record can be found by searching “Temple of Confucius in Qufu” (call number 3.1.19) in the library catalog.

Acknowledgment:

We would like to thank the University of Pennsylvania Archives and the Philadelphia Free Library for offering generous and timely assistance in locating Charles H. Lyon’s biographical information for us. The East Asian Library of Princeton University kindly created a detailed bibliographical description of the photos.

Time line:

1724: A lightning strike sparks a fire in the Temple of Confucius in Qufu, Shandong Province, destroying the statue of Confucius.

1730: The temple is restored after a five-year reconstruction project.

1872: KONG Lingyi, a seventy-sixth generation descendant of Confucius, is born in Qufu.

ca. 1874: Charles Hodge Lyon is born into a missionary family in China.

1877: As the first-born son of his family, Kong inherits the title “Duke Confucius.”

1898: Lyon graduates from the University of Pennsylvania with an M.D. degree.

ca. 1902: Lyon becomes a medical missionary in Tsining-Chou, China (now Jining of Shandong Province in northern China), serving as a physician at the Rose Bachman Memorial Hospital for Men.

1902: Lyon and Edna P. van Schoick are married in Shanghai on December 19.

1918: Lyon returns to the United States.

1919: Duke Kong dies in Beijing at age 47.

1937: Mrs. Lyon presents the photos taken by Dr. Lyon to John H. Scheide (Princeton class of 1896) on January 19.

1946: Lyon dies in Phillipsburg, New Jersey.

1966: Red Guards attack the Confucius temple, mansion, and cemetery, and destroy numerous antiquities, the statue of Confucius among them.

1983: The government funds the recovery of the Hall of Great Achievements, aiming for a faithful replication of the statues built in 1730.

1984: By August, all seventeen statues have been restored. The inauguration ceremony is held on September 22, speculated to be the 2,535th anniversary of the birth of Confucius.

Selected Bibliography:

“Charles Hodge Lyon.” Journal of the American Medical Association 131.6 (1946): 547. Web.

“Dr. C.H. Lyon Dies at Age of 72.” Philadelphia Inquirer Apr. 21, 1946: 10. Print.

Gao, Wen, and Xiaoping Fan. Zhongguo Kong Miao [Confucius temples in China]. Chengdu Shi: Chengdu chu ban she, 1994. Print.

“Going to China to Become a Bride.” The New York Times Oct. 25, 1902: 9. Web.

Gong, Yanxing, and Zhengyu Wang. Kong Miao Zhu Shen Kao [Deities in the Confucius Temple]. Jinan: Shandong you yi chu ban she, 1994. Print.

Kong, Fanyin. Yan Sheng Gong Fu Jian Wen [A history of the mansion of Duke Confucius]. Jinan: Qi Lu shu she, 1992. Print.

Pan, Guxi, et al. Qufu Kong Miao Jian Zhu [Architecture of the Confucius Temple in Qufu]. Beijing: Zhongguo jian zhu gong ye chu ban she, 1987. Print.

“Rose Bachman Memorial Hospital for Men.” Western Medicine in China, 1800-1950. Web. Apr. 19, 2013. <http://www.ulib.iupui.edu/wmicproject/node/336>.

Shandong Sheng wen wu guan li chu, and Zhongguo guo ji lü xing she Jinan fen she. Qufu Ming Sheng Gu Ji [Places of historical interest in Qufu]. Shandong ren min chu ban she, 1958. Print.

The Keys of the Kingdom. Dir. John M. Stahl. 1944. Film.