On February 21, 1838, New York book auction house Cooley & Bangs began a three day sale during which they offered more than 313 incunabula distributed among 1,302 lots. Many incunables came from the collection of George Kloss and had appeared in the London sale of his books three years before. It is entirely possible that the 1838 sale was the first time in America that so many incunables were offered all at once in a single auction.

One lot, number 537, “Biblia Germanica, wood cuts, 2 vol. fol. 1490,” eventually found its way to the shelves of the Princeton University Library. Its confirmed year of arrival is 1916. Where was the Bible between 1838 and 1916?

A ten page memorandum accompanying the Bible provides some answers. Minister of Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church in New York, the Rev. Dr. James Waddell Alexander (1804-1859), tells us in “Some Account of an Old Bible in the Hands of William Scott” that in 1856 it was owned by parishioner William Scott, who, other sources tell us, was said to be a friend and cousin of Sir Walter Scott, as well as a trustee of New York’s North Moore Street Public School. It is unclear how and why William Scott came to possess the Bible, but marks of both previous owners and the book trade clearly show that the Bible belonged to George Kloss, appeared as lot 748 in his 1835 London sale, and later appeared as lot 537 in the 1838 New York sale.

The link between William Scott and Princeton is Scott’s grandson, Laurence Hutton, who was a successful New York literary figure. Hutton relocated to Princeton in the 1890s, one of a several like-minded literary men who purposefully settled in town during that decade. Hutton owned this Bible and after he died in 1904, many of his books were shelved in the Exhibition Room of the Library. According to a 1916 account, they were part of “the Hutton Memorial Collection, consisting of several hundred books, autographed portraits, paintings, etc., from the library of the late Laurence Hutton, A.M. This collection was left by Mr. Hutton to trustees to be put in some safe place for a permanent memorial and was presented by them to the University.”

Library markings inside the Bible as well as catalogue records show that it remained part of the Hutton Memorial until about the 1930s, at which time it was re-classified so as to become part of the general collection of incunabula coded ‘ExI.’ It remains in the ‘ExI’ class down to today.

The Rev. Dr. Alexander’s memorandum is a remarkable document in its own right because it gives us a sense of the state of book history knowledge in the 19th century. Such evidence still remains scattered among a number of sources: trade journals, such as Joseph Sabin’s American Bibliopolist; major city newspapers; accounts published in larger works, such as Isaiah Thomas’s paragraphs in his History of Printing in America on an incunable Bible owned by the Mather family; as well as manuscripts in archives and other repositories.

A transcription of the memorandum follows:

Some Account of an Old Bible in hands of Wm Scott.

By Revd Dr. J.W. Alexander (Copy)

Another Old Bible

From time to time the newspapers give accounts of ancient printed Bibles. Our own columns have contained numerous statements of this kind; and we now add another, in a communication with which the Rev. Dr. Alexander of this city has favoured us at our request.

New York Feb. 1856

Rev. and Dear Sir.

The first part of a German Bible, belonging, to a worthy member of my charge, is probably unique in this country, and, as I observe by the books, is rare even in Europe. As you desire information respecting it, you will allow me to add a few statements concerning similar editions.

The old volume, which belongs to my esteemed friend, WM Scott Esq, has lost three leaves, including the title page, but is otherwise in excellent condition. It is bound in vellum, and has that remarkable brilliancy of ink, and depth of impression, which are matter of wonder in Early printing. The folios, (strictly so called, as that they are leaves, and not pages) are numbered, the last being 503. It contains the first part only that is from Genesis to Psalms, inclusively. The illuminated capitals are imitation of those which adorned manuscripts; the gilding and colours of these are well preserved. The coarse woodcuts are also highly coloured. The second page, or first after the title, begins with a German version of St Jerome’s Epistle to Paulines, introductory to the historical books. In the middle parts the paper is clean, and well kept. The exterior leaves are soiled, but here and there carefully repaired by insertions. The names of three former possessors, are very distinct, viz:

1. 1. In manuscript, “G.A. Michel, V.D.M.”

2. 2. On a ticket, under an engraved coat of arms “Matthias Jacob Adam Steiner.”

3. 3. On a ticket, “Georgius A. Klotz M.D. Francofurt ad Moenum.” Some owners, probably more recent than any of these, but long ago, as the faded ink shows have written the following bibliographical notes on the inside of the first cover, and the opposite fly leaf. From conjecture as to the age of the several entries, I arrange them thus, though their position is different, on the pages. (Translated.) “A defective part of a very uncommon, rare, and extremely, scarce Bible. I bought the same in 1772 from a book peddler for 24 gr. Still it remains a treasure and ornament of the library.”

2. 2. (Same hand.) In margin “I, 1785”, and then, “It appears to be an edition of the Bible, which on a/c of its iluminated figures was named the renowned or princely work (das durchlauchtige work;) and to have been printed in one thousand four hundred and eighty three, or eighty eight. (1483 or 1488.) Compare Hageman on Translations of the SS. page 263. Baumgartens Notices of remarkable books PI pp 97-101. Solgen Bible PI p.9. Schwartz part II p. 199.”

3. 3. (Same hand.) ” Concerning a translation of the Bible near the close of the fifteenth century, see Blaufus, Contributions to an acquatance with rare books, Vol. 1 p. 109.

4. 4. (In another hand.) “It appears to be a part of that rare and uncommon bible, which was printed in small-folio at Strasburg, without the printer’s house in fourteen hundred eighty five (1485.) (In margin, “A mistake, see preceding page.”) Vide Panzer, Literary Notices of the very oldest printed German Bibles, page 71, the X. m (sic)

5. 5, (Probably the same hand as the last.)

“From Panzer’s Extended description of the oldest Augsburg Editions of the Bible, p. 29 XII, it appears that this is certainly the first part of that German Bible which was printed at Augsburg in fourteen hundred and ninety, (1490) by Hans Schönsperger, in small-folios. For all the distinctive marks of this edition of Schönsperger which are there given, correspond most exactly with this copy.”

6. 6. (Another hand partly overrunning the ticket with Steiner’s name and arms.) “Panzers German Annals. T182, 285.

¶1ST Part

¶Twelfth complete German Edition of the Bible, Augsburg, Hans Schönsperger 1490.”

7. 7. (In pencil) “Wanting title page to fol 80 to 107.” (which corresponds with the fact.)

From the notes it is evident that this fine old volume though but a moiety, was considered highly valuable at least half a century ago. Panzer, who is several times cited above, is the celebrated Bibliographer of Nuremburg, who died in 1804, at a very great age. He devoted himself to the subject of Bible-Editions, and made a costly collection of these, which in 1780 passed into the hands of one of the Dukes of Wurtemburg. He published (1783 and 1791). “Outlines of a complete History of Luther’s version, from, 1517- 1581.” Two, at least, of Panzer’s more general works, are in the Astor Library. The vulgar error that there was no German translation before that of Luther should be corrected. The first that is certainly known, is that of the Vienna Library, and was made about 1466. (Montfaucon, a/c “Bible of Every Land p. 175.) Several authorities concur in staking the number of printed editions of the German Bible before Luther as fourteen in High German, and three in Low German. (Pischon , Einladungs, Schrift, & c. Berlin 1834).

To my friend and co-presbyter, Rev. Fred Steins of this city, I am indebted for the reference to Pischon below, as also for an extract from manuscript notes made by himself on the lectures of Professor Delbrück at the University of Bonn, in 1827, which was thus:

There were German Bibles before Luther, of which Panzer enumerates fourteen. From Panzen himself, we glean the following notice; The twelfth edition Augsburg, 1490, printed by Hans Schönperger, first part ends with Psalms, contains 503 Folios. (Annals, Vol.1.p.182.) Before the year 1578, there were only fourteen complete editions of the Bible in German, (p.9 & 99). Of these the first is the Mentz Bible, 1462, by Fust and Schöffer.

The first, with date on the title, is the sixth edition, fol. Augsburg, 1477. All these editions are described in Panzer’s Annals, a work which is in the Astor Library.

Before closing this dry and tedious letter, which may gratify one or two booksworms and collectors, let me say a word or two about the inside of the volume. It contains more than 70 woodcuts illustrative of the text, and, most significant in respect to the arts. Each of these extends across the page, occupying about one third of the letter press.

The Supreme Being is repeatedly delineated, under the figure of an old man. The cuts are highly colored. The patriarchs and prophets are represented in the garb of the fifteenth century, with tight hose, and pointed shoes. Jacob’s ladder is reared beside a lake or river, with quite a swell of waves, and a boat. Moses has the horns always accorded to him by Catholic and Medieval art. Naaman washes in Jordan, while a German carriage and pair, with pastillion, await him on the bank. Not far from a Gothic Castle, Queen Esther is attended by train-bearers, with middle-age coiffure. The pigment in every instance, is laid on boldly. In a word, the pictorial part is precisely in the manner of a clever child, handling his first paint box. This curious specimen of typography has now passed out of my hands, but I have supposed that as so much is said of volumes a century younger than this, you would have patience with some a/c of a pictorial Bible three hundred and fifty six years old. (In 1856).

I am very truly

Your friend and servant

James W. Alexander

(Copy)

Call number for 1856 memorandum:

C0323 Alexander Family Collection • Box 2, Folder 13

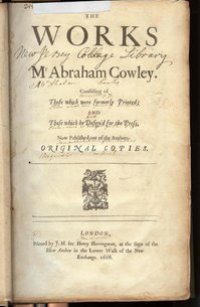

Example of illustrations:

Die Bibel. (Augsburg: Schönsperger, 1490) [ExI 5187.1490] v. 1, lvii verso – lviii recto, Exodus, chapter 9:

Plague 6. Boils

9:8 And the Lord said unto Moses and unto Aaron, Take to you handfuls of ashes of the furnace, and let Moses sprinkle it toward the heaven in the sight of Pharaoh.

9:9 And it shall become small dust in all the land of Egypt, and shall be a boil breaking forth with blains upon man, and upon beast, throughout all the land of Egypt.

Plague 7. Thunder and Hail

9:18 Behold, tomorrow about this time I will cause it to rain a very grievous hail, such as hath not been in Egypt since the foundation thereof even until now.