Mestiçagem or Multiculturalism? How Transformations of Brazilian Pop Anthem Question Ideals of Racial Democracy and Class in Brazil

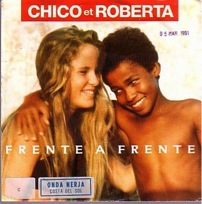

“Chorando se foi” by Kaoma (1989) and “Taboo” by Don Omar (2011) are two music videos portraying different versions of the same Brazilian song, with the former set on the Bahia Islands of Brazil and the latter in Rio de Janeiro. Kaoma is an Afro-Brazilian group, while Don Omar is a reggaeton star from Puerto Rico. Set twenty years apart, and despite the different racial paradigms and intended audiences of the speakers, there are several loose parallels between the videos’ plots and basic narratives of romance. However, the two videos, while lyrically quite consistent, are in form much more different than similar—and the ways in which they differ are extremely telling. 1 2 Kaoma creates a narrative within the first music video more akin to the ideology of mestiçagem, initially put forth by Gilberto Freyre in the 1930s (and having a resurgence in the 1980s) as ‘the most powerful myth of national origin produced by any Brazilian intellectual’ (Cleary, 1999: 8). “Chorando se foi,” on the other hand, questions the plausibility of mestiçagem as a functional means of racial democracy, suggesting it may have had to do more with avoidance of dealing with serious racial issues than anything else. This essay will seek to further explore the differences in representations of body, beauty, and race in Brazil—and address why these differences matter.

Scholars on race in Brazil define mestiçagem as a ‘cultural paradigm that represents the nation as racially mixed and which deemphasizes clear racial boundaries between groups’ (Edmonds, 2007: 85). It could even be argued as a form of compensatory patriotism that Brazilians dark and light alike embrace. It’s defined by those who embrace it as the idea that Brazil is partaking in miscegenation in order to create a pure, by nature of being mixed, Brazilian race. It attempts in its foundation to establish a racial democracy–equalizing blacks, whites, and mestizos by celebrating the beauty of a healthy medium, a mixed race, a reunification of previously separated groups. Such an elusive ideal was partially established to quell the varying sentiments of different races within the country, and also to enable Brazil, ‘despite its disadvantaged racial stock, to be transformed into a modern nation’ (Twine, 1998: 88). It is clear to many that mestiçagem is idealistic, but it is this very idealism that has enabled this notion to thrive in Brazil.

Don Omar brings a contemporary, perhaps nuanced view to the politics of body, beauty and race in Brazil; he offers a perspective suggestive of their being an overly idealistic notion to mestiçagem in the country, reflecting an ideal perhaps more closely associated with multiculturalism. Multiculturalism “is the political expression of cultural relativism. The starting point for all relativisms is the relationship between knowledge and the social and cultural context in which it came about” (Zarur ****4). Multiculturalism allows for the coexistence of multiple cultures or groupings alongside one another, without actively promoting their intermingling. This difference in viewpoint in fact parallels the lack of clarity in identifying the presence of, and therefore solutions to, race problems in Brazil.

The young couple in Kaoma’s video who serve as protagonists are able to overcome the racial differences that could potentially bar their happiness. Their love from the beginning is posed as a mutual one, fueled by passion on both sides. They both see the beauty in the other, thus creating a representation of beauty that is not delineated by racial lines, that is consummated by their dancing lambada. At a predominantly Afro-Brazilian party, the girl and her father are the only people who appear Euro-Brazilian. The father at first separates his daughter from the boy; he disapproves of her dancing with a black boy. However, as he moves to break them up again after they continue to dance, he apparently has a moment of revelation, an epiphany that illuminates the beauty of mestiçagem.An Afro-Brazilian woman begins to dance with the father and he is entranced by her beauty 3 However, what the video most poignantly symbolizes is not the individual beauty of whites and blacks respectively, but rather the greater beauty of their coming together. There is such joy associated with the unification of blacks and whites. It implies that mestiçagem is a positive force as it creates ‘one distinct (and aesthetically superior) national idea of beauty’ (Edmonds, 2007: 94).

The representations in this first video further imply that racial tension in Brazil is not really an issue anymore. While the father was cautious in the first part of the video, actions symbolic of mestiçagem ameliorated his fears and erased these tensions. The video concludes by zooming away from a scene of everyone dancing, blacks and whites alike and finishing on a note both positive and somehow indicative of closure (see footnote 3 above). Part of this quite happy-ending outcome might be attributed to the fact that the video was produced by a group of darker-skinned Brazilians themselves, and that it came out in the late 1980s during mestiçagem’s resurgence, perhaps revived to coincide or assuage concerns of racial disparities as a result of Brazil’s rapidly growing in economy that resulted from the fall of the dictatorship. It has also been observed that mestiçagem is often more pushed by Afro-Brazilians as they are the ones who would benefit most from upward mobility (Twine, 1998: 88). For international viewers of this video, representations of beauty and race make it appear that Brazil has a very healthy perspective on race relations. Omar later begs to differ.

Academics more critical of modern Brazil define mestiçagem in its application as ‘the valorization of whiteness and the movements away from blackness’ (Twine, 1998: 107). Mestiçagem, in this view, does not create equity among races by embracing a mixed race so much as it suggests that upward mobility in social spheres is made possible through miscegenation—that people’s races do continue to play a huge role in their ability to succeed financially and socially, implying that there is a different color people should aim for.

Don Omar’s musical prowess led him to Brazil many times, and his video suggests a somewhat different take on the blithe assumptions of mestiçagem. His remake of “Chorando se foi,” finished in 2011 and known worldwide, begins similarly to that of the original—at a party. However the guests are all Euro-Brazilian, and the party seems to be of a much more wealthy nature. 4 This representation establishes a relationship between skin color and social class, as Don Omar, presumably posing as an Afro-Brazilian or just of darker skin color, is only at the party because he is serving as a caterer—reflecting a presence of racial insuperiority as ‘darker Brazilians are excluded from a range of social institutions,’ like these elitist parties (Telles, 2004: 16). At the party, Omar crosses paths with a woman whom he knew from childhood (see footnote 4 above). Memories of a relationship that never panned out perhaps due to the fact that ‘Euro-Brazilian elites typically live class-segregated lives and rarely, if ever, seriously consider marriage or close friendships with individuals outside of their class positions’ cause Don Omar to flee the party and head toward home in the favelas (Afro-Brazilian-dominated slums) (Twine, 1998: 104). He sings to her “vélame en las favelas,” find me in the favelas, which means that in order for her to meet him, she would have to “lower” her position in the class system by leaving the party (see lyrics in footnotes 1).

“Taboo’s” lyrics, while partly sung in Spanish, do not deviate much from the original song’s (see lyrics in footnotes 2). They do, however, further expand on the beauty of the main female character. She is “una sirena” (a siren) and “dicen que está tomando el sol” (lying in the sun, an act more specific to whiter women). She has “un cuerpo que pide a gritos” (a quite fantastic body). The woman that Don Omar is singing about is, as in the original video, a white woman. The emphasis on her specific beauty, however, isn’t as strong in the original, when herbeauty, her white, blonde, blue-eyed version of beauty is why she attracts the most attention.

The combination of the woman’s white dress and airy gait makes her seem virginal or angelic. 5 Her beauty then is pure, and different, from the Afro-Brazilian women in Omar’s video, who are dressed in revealing clothes and have body language that further sexualizes them. While the woman in the original walks calmly, these women shake their butts and grit their teeth 6 She is angelic and they are animalistic. Yet despite their sexualization, it is the virginal, innocent white woman who elicits more sexual desire from the men. This is perhaps reflective of the idea that black women ‘have cultivated an image which suggests they are sexually available and licentious,’ in fact so sexual that they become ‘undesirable in the conventional sense’ (hooks, 1997: 117). In the favelas, black men whistle and blow kisses at the white woman—thus extending this sexualization across gender lines. This thematic structure is not aligned with the presumptions of mestiçagem. Omar’s video portrays the white woman as the most desirable, without portraying the black women or men in a similar way. In fact, the relationship that mestiçagem seeks to build ‘between morenidade and modernidade, so that brownness becomes not a barrier to modernity, but its sensual and democratic realization’ is not evident at all in Omar’s video, who as a foreigner sees the country, in 2011, as far more split by color and socio-economic positions (Edmonds, 2007: 372).

Unlike the conclusion to Kaoma’s video that is very much a “happily ever after,” Omar’s video leaves viewers unsettled. The woman finally finds Omar at the favela party and follows him upstairs. Before they consummate their relationship, though, she switches clothes with an Afro-Brazilian woman and reappears in a considerably more revealing outfit (see footnote 6 above). The purity of her white dress, easily construed as a representation of her own race, is shed in the act of miscegenation. The video suggests that racial equality is not achieved on any form of common ground; rather, it implies that one group must be raised or lowered in miscegenation.

The differences between Kaoma’s and Omar’s videos reflect the problematic nature of the overly idealistic mestiçagem, and beg that a closer look be taken at their quite conflicting messages. Those watching Kaoma’s video might be under the impression that mestiçagem is in full force in Brazil—not only encouraging integration of the races but celebrating it. But “Taboo” is more representative of ideas of multiculturalism, accepting and promoting the existence of multiple cultures within a society, without necessarily encouraging overlap or integration. “Taboo” does a fair job in implying that notions of beauty and race relations in Brazil, and how they overlap with class, are maybe guided more by the passive and separating nature of multiculturalism rather than mestiçagem. The reality of this divisive multiculturalism in “Taboo,” though, still indicates that those with paler skin are still generally of a higher class, are still put on a pedestal of beauty, a characteristic incredibly determinant of success in Brazilian society and economy. Blacks and mulattos, on the other hand, do not benefit as well. Even though current views of mestiçagem make it possible for blacks to achieve upward mobility in a multicultural society, that mobility only comes as a result of whites’ class positions inevitably being lowered. The eternally pesky double-edged sword.

In the two videos, the artists call into question the national ideals motivating race relations in Brazil; Kaoma representing mestiçagem as more present, and Don Omar’s video more implicative of increasing trends in multiculturalism. It seems clear that mestiçagem can easily blind people to the racial disparities that exist. Don Omar’s nuanced remake of Kaoma’s “Chorando se foi” suggests multiculturalism is more indicative of a more contemporary trend in Brazilian soceity—endorsing cultural pluralism without addressing or encouraging mixing—and that the overly simplistic ideal of mestiçagem must be seriously questioned: the illusion of harmony it creates is doing more harm than good in enabling Brazil to deal with the ever tricky business of race relations. However, multiculturalism is not a solve-all solution to mestiçagem either. It is another ideal that can be “designed to aggrandize the established powers and thereby legitimize existing systems of domination and subordination” (Abbas 28-29). There is no answer yet, nor perhaps might there ever be, as to the best way in which to deal with race relations in Brazil. However, representations in these two videos do articulate various problems associated with both mestiçagem and multiculturalism, suggesting some form of a middle ground or nuanced policy must be explored

References

Carlosgodoy80, 2009. Kaoma- Chorando se foi- Lambada. Available at: <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gQaT8KtJK2E> [Accessed 20 April 2012].

Cleary, D. (in press) “Race, nationalism and social theory in Brazil: rethinking Gilberto Freyre.” David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies (Accepted for publication in 1999).

DonOmarVEVO, 2011. Don Omar- Taboo. Available at: <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lRWqYR3e7xE&ob=av2e> [Accessed 20 April 2012].

Don Omar (2011) Taboo. Universal Latino.*

Edmonds, A. (2007) ‘‘The poor have the right to be beautiful’: cosmetic surgery in neoliberal Brazil’, Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 13, 1, 363-381.

Edmonds, A. (2007) ‘Triumphant Miscegenation: Reflections on Beauty and Race in Brazil’, Journal of Intercultural Studies, 28, 1: 83-97.

Hobson, J. (2005) Venus in the Dark: Blackness and Beauty in Popular Culture. New York: Routledge.

hooks, b. (1997) ‘Selling Hot Pussy: Representation of Black Female Sexuality in the Cultural Marketplace’ in K. Conboy, Medina, N. & Stanbury, S. (eds.) Writing on the Body: Female Embodiment and Feminist Theory, New York: Columbia University Press, 113-128.

Kaoma (1989) Chorando se foi (Lambada). Lambada Records.*

Telles, E. (2004) Race in Another America: The Significance of Skin Colon in Brazil. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Twine, F. W. (1998) Racism in a Racial Democracy: The Maintenance of White Supremacy in Brazil. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

*Both sets of lyrics disputably unauthorized translations of following song: Gonzalo Hermosa González (1981) Llorando se fue. EMI Records.

Footnotes

- Lyrics “Chorando se foi”

Lyrics according to following site: http://lyricstranslate.com/en/Lambada-Lambada.html

“Chorando se foi (Lambada)”- Kaoma (1989)

Lyrics originally written by Los Kjarkas in 1981, Kaoma’s version is unauthorized translation.

Chorando-se foi quem um dia só me fez chorar / Chorando-se foi quem um dia só me fez chorar / Chorando estará ao lembrar de um amor / Que um dia não soube cuidar / Chorando estará ao lembrar de um amor / Que um dia não soube cuidar

A recordação vai estar com ele aonde for / A recordação vai estar pra sempre aonde eu for / Dança, sol e mar, guardarei no olhar / O amor faz perder encontrar / Lambando estarei ao lembrar que este amor / Por um dia, um instante foi rei

A recordação vai estar com ele aonde for / A recordação vai estar pra sempre aonde eu for / Chorando estará ao lembrar de um amor / Que um dia não soube cuidar / Canção, riso e dor, melodia de amor / Um momento que fica no

“Crying she went (Lambada)”- Kaoma (1989)

The one who made me cry has gone crying one day / The one who made me cry, has gone crying one day / He’ll be crying when he remembers a love / That he didn’t care one day / He’ll be crying when he remembers a love / That he didn’t care one day

The memory will be with him where he goes / The memory will be forever where I go

Dance, sun and sea I’ll keep on my look / Love makes (us) lose and find / I’ll be dancing lambada when I remember that this love / One day was king for an instant

The memory will be with him where he goes / The memory will be forever where I go

He’ll be crying when remembers a love / That he didn’t care one day / Song, laugh and pain melody of love / A moment that lasts in the air ↩

- Lyrics of “Taboo” by Don Omar

Lyrics according to following site: http://lyricstranslate.com/en/taboo-la-lambada-taboo.html

“Taboo”- Don Omar (1981)

Lyrics originally written by Los Kjarkas in 1981, Don Omar’s version has minor additions added by himself.

Bahía Azul! / el roce de los cuerpos al ritmo de la musica / A & X! / Taboo! / (Calor!) / Anda Depresivaaa ! / (Pasión!) / No llores por él! / (No llores por él!)

Llorando se fue la que un día me hizo llorar / Llorando se fue la que un día me hizo llorar / Llorando estará recordando el amor / Que un día no supo cuidar (hay loba!) / Llorando estará recordando el amor / Que un día no supo cuidar (Brasil!)

A recordação vai com onde eu vou / A recordação vai estar pra sempre onde eu vou / Dança, sol ei mar guardarei no ollar / O amor vai querer encontrar / Lambando estarei ao lembrare que este amor / Por um dia um instante por rei

Soca en San Pablo de noche, la luna, las estrellas / La playa, la arena para olvidarme de ella / una sirena que dicen / que esta tomando el sol

Uh! Oh-Oh! / Un cuerpo que pide a gritos / Samba y calor / Uh! Ohi oh!

Mi nena, menea! / Una cintura prendida en candela / Mi nena, menea! / No se cansa / Mi nena, menea! / Bailando así / Mi nena, menea! / Ron da fao, ron da fao / Mi nena, menea! / Matadora! / Mi nena, menea!

Velame en las favelas / Velame en las favelas / Velame en las favelas

“Taboo”- Don Omar

Blue Bay! / the rustle of bodies to the beat of music / A & X! / Taboo! / (heat!) / she goes depressively ! / (Passion!) / Don’t cry for him! / (Don’t cry for him!)

Crying went the one who one day made me cry / Crying went the one who one day made me cry / Crying she will be remembering the love that one day didn’t know how to take care (ay wolf!) / Crying will be remembering the love / that one day didn’t know how to take care (Brazil!)

The memory goes with me where I go / the memory will be always where I go / dance , the sun ,the sea , will keep to look / you’ll want to find a love / lambando you’ll remember this love / for an instant this love was king

Alone in Sao Paulo the night, the moon, stars / The beach, sand to forget her / a siren that they say / is taking the sun / Uh! Oh-Oh! / A body asking to shout / Samba and heat / Uh! Ohi oh!

My baby, wiggles! / A waist turning in candle / my baby, wiggles! / She doesn’t get tired / My baby, wiggles! / dancing like that / My baby, wiggles! / Ron da fao, fao da rum / My baby, wiggles! / murderess! / My baby, wiggles!

Find me in the slums / Find me in the slums / Find me in the slums ↩

- Summary of Music Video

Video can be found: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gQaT8KtJK2E

The music video of “Chorando se foi” was an equally popular component of the song. Filmed in both the Tago Mago Island of the Mediterranean and Cocos Beach in Bahia, Brazil, the setting of the video is intended to appear as just Brazil. There is a party occurring on a small beach side bar, with many darker-skinned or Afro-Brazilians composing the majority of attendees. They are all dancing the new and popular lambada. The only whiter-skinned people are what appear to be one of the bar mangers and his daughter. The young white daughter and a young black boy attending the party become the protagonists of this plot when they meet eyes and decide to dance lambada together. The father gets mad that his daughter is dancing with the black boy and separates the two. However, their quickly growing liking and longing for one another doesn’t allow them to stay apart. They dance together again, towards the beach. As the father comes, angry, to separate them once more—he is intercepted by an adult black woman who begins to dance with him. All his previous anger melts as he is also now in a biracial dancing partnership, united over lambada ↩

- First section of narrative: The first part of the video is in the setting of a very ritzy looking party in a huge mansion house. The attendees of the party are all white, or light-skinned mestizos. Don Omar, however, is a darker-skinned/black caterer at this party. He comes across a white woman which jogs his memory of a childhood crush they had on one another, then spills the drinks he is about to serve and leaves the party—clearly out of place and quite out of sorts. ↩

- Second section of narrative. In the second part of the video, Don Omar is now singing from the window of a favela home while the white woman goes off in search of him, shedding her white sweater at the party before venturing out into what appears to be the “wild” parts of Brazil. She ventures on the beach, through the streets, and eventually through the favelas (while Don Omar sings “Vélame en las favelas”…). All of the men on the street stare at her and you can tell her beauty does not go unnoticed by them as even the kids blow her kisses. As she goes towards the favelas, the people she encounters become darker and darker in skin tone. The men who help point her in the direction clearly desire her and the women she asks for help have too much attitude to really even give her the time of day. The white woman, in the white dress, with blonde hair and blue eyes, clearly stands out in these rougher zones of Brazil. ↩

- Third section of narrative. Finally, as the white woman gets closer and closer to Don Omar’s location—he is now singing from a party scene where many dark-skinned woman are dancing in very scantily clad outfits such as bikinis, with wild and undone hair as compared to her straightened blonde hair. There are vibrant colors characterizing their dress, while she is wearing white. They dance quite sexually, shaking their butts and grinding upon men, while she floats through the favelas in an almost angel-like, virginal way. Don Omar, at the party, is being sexually accosted by many of the more wild women as he sits in a throne-like chair, and the scene almost reflects a strip club. Finally, the blonde woman arrives to the party and Don Omar, seeing her, leaves to a room upstairs. The woman goes to find him, but not before exchanging her white outfit with the more “traditional” or “exotic” wear with a black woman at the party. She is then clad in a short skirt and a sequined top. Having changed her outfit, she enters the room where Don Omar is sitting and they proceed to have what can be assumed are sexual relations. ↩