Nancy Cock’s Song-Book. [London]: Printed for T. Read, [1744]. (Cotsen 7262290)

Old Mother Hubbard and the antics of her dog is another classic of English nonsense that has made people in Europe laugh too, a fact that you won’t learn from the indispensable Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes. The Opies recorded the continuation and a sequel “by another hand” issued shortly after the John Harris first edition of 1805, imitations like Old Mother Lantry and her Goat (1819), the first pantomime version of 1833, and a translation into German ca. 1830.

The Comic Adventures of Old Mother Hubbard and Her Dog. Illustrated by Robert Branston? London: J. Harris, 1820. (Cotsen 3688)

What the Opies didn’t make clear is that it was the 1820 edition in Harris’s “Cabinet of Amusement and Instruction” with the hand-colored wood engravings attributed to Robert Branson that captured imaginations overseas, not the original edition illustrated with etchings. See the beautiful high-relief carvings of the amazing dog’s head in the corners of the elaborate gilt frame of the good old lady’s portrait?

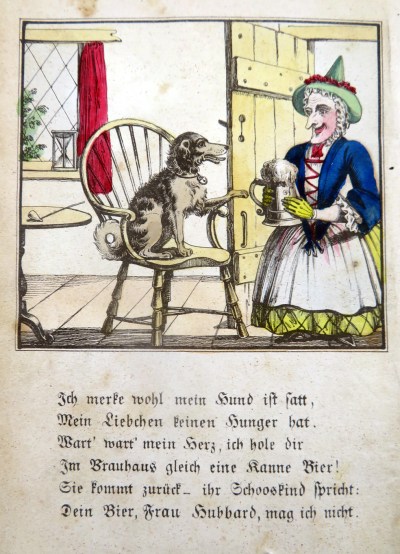

Her steeple-crowned hat on top of a mob-cap, the gown with a laced stomacher and ruffled sleeves over a quilted petticoat, became iconic internationally, as did her dog’s ensemble of an opera hat, powdered wig, waistcoat, breeches, stockings with clocks and buckled shoes. They are both unmistakable in the New Adventures of Mother Hubbard, when they visit the sights of London ca. 1840, the year Victoria married her cousin Albert.

Cock Robin and the New Mother Hubbard. London: James March, not before 1840. (Cotsen 26792)

Audot published a French prose translation, Aventures plaisantes de Madame Gaudichon et de son chien, in 1832. Baumgaertner in Leipzig quickly picked it up and repackaged it as an entertaining text carefully annotated for German-speaking children to learn French. The dog is named “Zozo” here (he isn’t called anything in the English original).

Aventures Plaisantes de Madame Gaudichon et de son Chien. Leipzig: Baumgaertners Buchhandlung, [ca. 1830]. (Cotsen 3708)

Komische Abentheuer der Frau Hubbard und ihrein Hunde. Mainz: Joseph Scholz, ca. 1830. (Cotsen 23460)

Mother Hubbard and her spaniel turn up in an 1840 Baumgaertner picture book, Herr Kickebusch und sein Katzchen Schnurr, which seems to be inspired partly by old Dame Trot, the owner of a clever kitty, whose rhyme predated the first appearance of Mother Hubbard both in English and in German translation by a few years. The story accompanying plate VIII describes how Madame Kickebusch, the lady in the Mother Hubbard costume comes to visit Herr Kickebusch with her gallant little gentleman, Azor. Here the two pets are being introduced to each other.

Herr Kickebusch und sein Kätzchen Schnurr. Leipzig: Baumgärtners Buchhandlung, 1840. (Cotsen 5450)

There are no less than four Russian translations of Alice in Wonderland, included one by Vladimir Nabokov, so why not two radically different ones of Mother Hubbard? Russia’s first fine art book publisher Knebel’ was responsible for the earlier one. Josef Nikolaevich Knebel is a fascinating figure, who apparently had no scruples about issuing unauthorized reprints of famous modern Western European picture books like Elsa Beskov’s Olles skifard and Tomtebobarnen. There are no clues in Knebel’ translation of Mother Hubbard, Babushka Zabavushka i sobachka Bum [The Jolly Grandma and her Little Dog Boom], as to who wrote the text or drew the pictures. The mystery author was Raisa Kudasheva (1878-1964), who also translated the Knebel rip-off of one of the Beskow picture books. While the illustrations are in the unmistakable style of W. W. Denslow, whoever drew them was not copying the American’s version of Mother Hubbard.

Raisa Kudasheva. Babushka Zabavushka u sobashka Bum. Moscow: I. Knebel’, ca. 1906. (Cotsen 27721)

Of all the versions here, perhaps the closest to the spirit of the English nursery rhyme is the poem Pudel’ [Pudel] by the great Soviet children’s poet, Samuil Marshak. In some people’s opinion, Marshak beats the original cold and they may have a point. To what extent the inspired illustrations by Vladimir Lebedev play into this is impossible to say. It begins something like this: An old lady who loves a quiet life drinking coffee and making croutons. Or would, if she didn’t own a rumbustious purebred poodle. She decides to get him a bone for lunch out of the cupboard, but what does she find inside? The poodle!

Samuil Marshak. Pudel’. Illustrated by Vladimir Lebedev. Moscow, Leningrad: Raduga, 1927. (Cotsen 26976)

There is no end to his naughty tricks. This is what happens when he gets his paws on the old lady’s ball of knitting wool…

Marshak’s spin on Mother Hubbard is still so beloved in Russia that an animated film was made by Nina Shorina in 1985. This version on You Tube has optional subtitles so the poetry and pictures can be enjoyed together by non-Russian speakers.

A world traveler, this very English bit of nonsense!