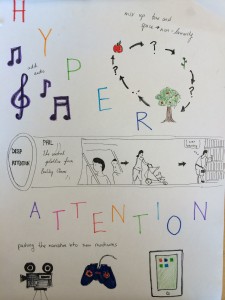

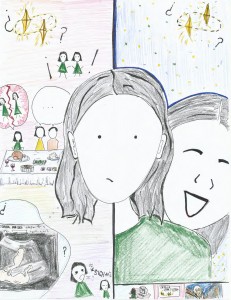

In my visual proposal, I attempted to depict hyper attention with a simple two dimensional drawing. Specifically, I hoped that I could introduce (using symbols) new media into Chris Ware’s Building Stories (specifically the storyline of Phil) in order to force readers to engage in a hyper attention form of thinking. However, I believe that experiment to have failed because it only symbolically and very tangentially applied the idea of hyper attention. Furthermore, I came to an understanding that in many ways Ware’s texts are already a sort of hyper attentive model — many different types of books that you can pick up and put down, and so forth. However, they still retain some notion of deep attention in that you can focus on only one book at at time. Despite this, Chris Ware’s overlapping narratives scattered among different books in Building Stories provide a perfect opportunity to capitalize on the needs of hyper attention. Now, I revise both the subject and the medium through which I do this, in hopes of transforming it into a true model of hyper attention.

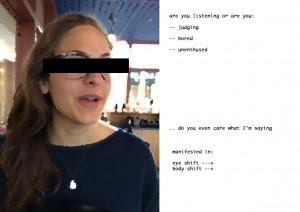

Hyper attention, according to N. Katherine Hayles, a professor at UCLA, is characterized by the following:

— Rapidly switching among different tasks, and excellent ability to handle this change in environment.

— A preference for multiple streams of information

— Involves a high level of stimulation

— Ability to handle environments where multiple things compete for attention.

— Impatience with non interactive objects

Source: Hyper and Deep Attention: The Generational Divide in Cognitive Modes by N. Katherine Hayles.

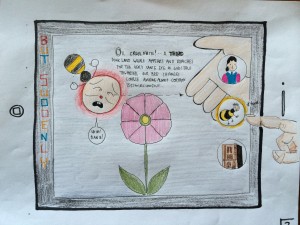

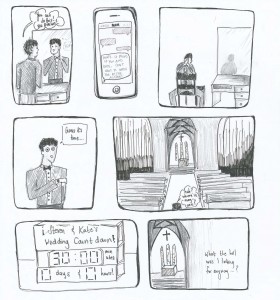

Here, a single narrative (which is recognizable as the demise of Branford Bee) is envisioned as an iPad app which caters to the hyper attentive model of thinking. The narrative is actually told from three different perspectives in two different books.

The iPad app allows the user to toggle between perspectives of different characters (see the three icons on the right of each iPad ‘screen’) without differentiating between the different books. Instead, it organizes the narrative by time and collapses all parts of the same story contained within various books into a single sequence. Interdependent parts of the narrative (i.e. that the girl must open the window before Branford can escape) must be played out by the reader/user before the narrative continues along. The reader/user moves the characters along the page until they reach their final destination as indicated in Ware’s original text/drawing. i.e. in panel 1, the actual image is of the girl pouring detergent in to the washing machine. As the finger swipes her along this path, she will move towards the laundry machine and pick up the detergent.

By rendering Building Stories in this fashion on the iPad, I capitalize on several key components of hyper attention. First is the ability to focus on multiple information streams, which comes from being able to shift perspective between different characters. Secondly, the objects become interactive, in that the user must guide the narrative forwards by making characters move towards their destination (i.e. Ware’s actual drawing). Furthermore, there are multiple points of attention, since the user must simultaneously propel all the different narratives forward by toggling between characters and checking if their story can continue at a given time. Hopefully, the below storyboard brings these ideas to life.

1. The current perspective is the girl’s. In Ware’s original panel that this image depicts, the girl is pouring the detergent into the washer. The user (the hand) swipes her across the screen until this image is shown, at which point this panel’s interactivity and narrative have been completed.

2. The user toggles to Branford Bee’s perspective, whose current narrative is of the approach of the girl in the laundry room. However, because the user has not reached the panel in the girl’s perspective where she opens the window, the user cannot “move forward” in Branford Bee’s perspective.

3. The user toggles back to the girl’s perspective and moves through the panels until she opens the window.

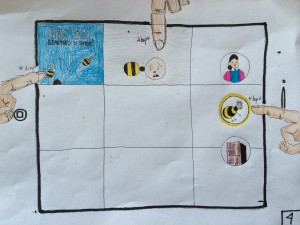

4. The user toggles back to Branford Bee, who can now escape. In this 3 by 3 grid, the user taps one by one on each of the mini panels in order to move the narrative forward.

5. By the end of the above 3 x 3 grid, Branford Bee is flying free and towards the drop of soda on the stair. Thus, when the user toggles to the building’s perspective, we see the image of exactly this happening as Chris Ware depicts it.

Panel 1 comes from the game board; panel 2 comes from the back of the Branford Bee booklet (red cover); panel 3 comes from the game board; panel 4 comes from the Branford Bee booklet; panel 5 comes from the game board.

Note that the prequel to this narrative is contained in The Daily Bee (where Branford gets stuck in the house to begin with!) providing more fodder for the iPad app!