“My dismay at the clutter on my desk is offset by my zest for the hunt among my papers. At an age when I should be putting my house in order, I keep accumulating bits of information, not for any particular reason and in spite of the absurdity, because I was born curious and don’t know how to stop.”

Stanley Kunitz, “Seedcorn and Windfall” from Next to Last Things: New Poems and Essays (1985)

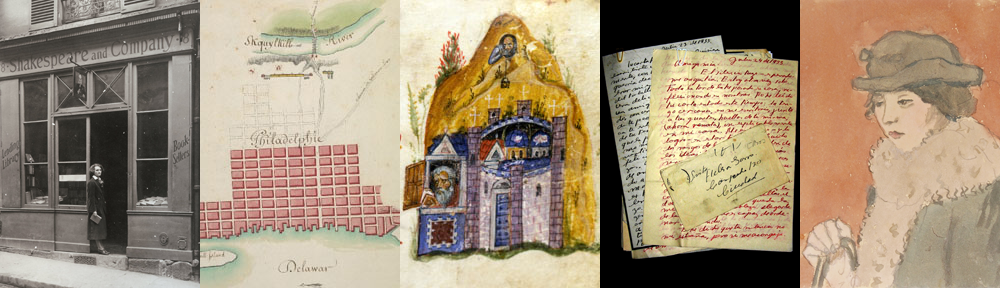

Born curious, the Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Stanley Kunitz [1905-2005] lived a long and varied life. Beyond the critical acclaim he gained for his poetry, Kunitz and his wife, the painter and poet Elise Asher, were friends to many of the 20th century’s cultural giants: painters like Mark Rothko, Philip Guston, and Robert Motherwell; and poets like Robert “Cal” Lowell, Marianne Moore and Elizabeth Bishop. The couple split their time between their Greenwich Village apartment and Provincetown, MA, where Kunitz raised a seaside garden, and they traveled extensively.

A restless spirit, Kunitz helped found the Fine Arts Work Center, an artist-residency program in Provincetown, and Poets House in New York City, two organizations that would help support generations of younger poets. By the time Princeton University’s Rare Books and Special Collections acquired Mr. Kunitz’s papers, the aging poet had indeed amassed a certain amount, as he wrote, of clutter. Clutter – perhaps – but it was good clutter, constituting a trove of research material for literary scholars and art historians alike. Available for research, the Stanley Kunitz Papers offers a complete finding aid, documenting the life and work of one of the United States’ most prominent poets.

In Stanley Kunitz’s own words, “it was not an auspicious beginning.” [“My Mother’s Story,” TMs, Box 147 Folder 11] Bereft of a father and the only son of an Eastern European immigrant mother, Stanley Kunitz grew up in Worcester, MA, where he spent a good deal of time out of doors. At an early age Kunitz became enthralled with the natural world, a theme that is recurrent in his poems, such as this one, “The Testing Tree”:

Once I owned the key

To an umbrageous trail

Thickened with mosses

Where flickering presences

Gave me right of passage […]

His fascination with comets, insects, whales, birds, raccoons, and the ways of plants and flowers informs his most enduring poems. While Kunitz did explore political and social themes throughout his work, the notes, subject files and clippings in the Stanley Kunitz Papers confirm his abiding passion for the natural world. Equally at home in the flower bed and at the typewriter, his last book, The Wild Braid: A Poet Reflects on a Century in the Garden (2005) examines the synthesis of these two vocations. Manuscripts of this book and others demonstrate Kunitz’s deliberate and sustained writing practice, no doubt informed by the patience, persistence, and an eye to detail refined by a lifetime working the garden.

Beyond the manuscripts, the Papers give access to reams of correspondence between Kunitz and the literati and glitterati of the 20th century; fan letters spanning five decades; the peace-loving poet’s military discharge papers and his father’s death certificate; drawings sent to him from his poet friends; poems written by his artist friends. Many items invite investigation, such as the Russian translations, some of which remain unpublished; Elise Asher’s recipe for Cream of Sorrel Soup;the unidentified correspondence; and fragments of possibly unpublished poems.

Among the most tantalizing materials are the photographs [Box 183]. Whether pictured with fellow poets, Jorge Luis Borges at Columbia University, or deep in conversation with Mark Rothko, the photographs testify to Kunitz’s active engagement in the world of arts and letters. As a poet among painters, Kunitz gained entrée into some of the most legendary cultural scenes of the 20th century, like “The Club,” which Kunitz characterized as “the stormy social and debating society of the New York School” [“Giorgio Cavallon 1904-1989,” Box 146, Folder 10]. The combination of Kunitz’s own intellectual achievement and his personal friendships makes the Stanley Kunitz Papers a valuable resource for researchers across the humanistic disciplines.

Mark Rothko and Stanley Kunitz, undated. Box 183, Folder 17. Not to be reproduced without the permission of the Princeton University Library.

Front row (L to R): John Berryman, Adrienne Rich, Josephine Jacobsen and James Merrill; Back row (L to R): Kunitz, Richard Eberhart, Robert Lowell, Richard Wilbur, William Meredith (Class of 1940) and Robert Penn Warren. Box 183, Folder 7. Not to be reproduced without the permission of the Princeton University Library.

You must be logged in to post a comment.