Unbearable torments and punishments awaited the wicked in Hell, according to the ancient Persian prophet Zoroaster (Zarathustra), who lived at some point between 1500 and 600 BCE. His teachings inspired the Zoroastrian religion, which flourished in pre-Islamic Persia and has managed to survive until the present day among the persecuted Zoroastrian minority in parts of Yazd and Kerman, in northeastern Iran; and among the Parses (meaning Persians) of India, about 200,000 of whom live in Mumbai (Bombay) and its environs. From there, the Parses have brought their faith to other places, including the Princeton area. Surviving Zoroastrian texts describe Hell as a fiery, stench-filled place for men and women guilty of sins ranging from murder, sodomy, and sorcery, to bad administration, perjury, and other crimes against the social order. Punishments meted out in Hell include torture, mutilation, dismemberment, and immolation. Depictions of these punishments can be found in the relatively uncommon Zoroastrian illustrated manuscripts preserved in major research libraries.

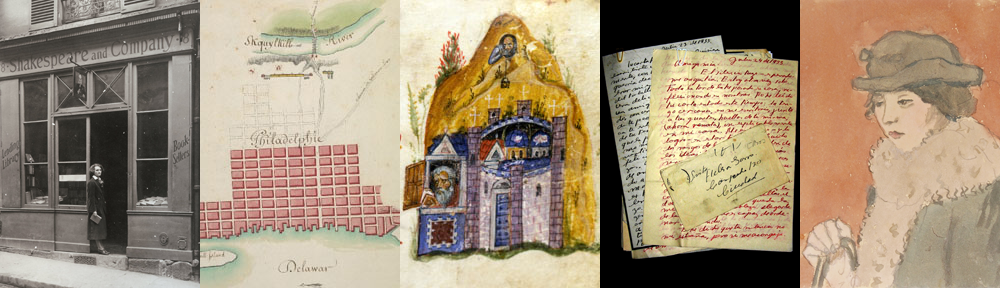

The Manuscripts Division is fortunate to have a particularly attractive example: Islamic Manuscripts, New Series, no. 1744, possibly dating from the year 1589. This manuscript contains Sad dar, Arda Viraf, and other Zoroastrian texts, written in Persian and illustrated with fifty miniatures of Heaven and Hell. See the miniatures below for particularly vivid scenes of armed demons, snakes, and wild beasts attacking the unfortunate souls consigned to Hell. The Library digitized this manuscript for the Digital Princeton University Library (DPUL), where it may be accessed at this URL. It is one of more than 1,600 manuscripts in the growing Princeton Digital Library of Islamic Manuscripts. As one can see online, the manuscript was living in its own kind of Book Hell. When acquired by the Library, perhaps a half century ago, the manuscript was disbound and badly worm-damaged, like many manuscripts of Iranian and Indian origin. In this compromised condition, it was difficult for the manuscript to be handled by researchers or shown to Near Eastern Studies classes without further damaging it. The volume needed full conservation treatment. Over the course of weeks, as time allowed, the manuscript was expertly flattened, mended, and rebound by Mick LeTourneaux, the Library’s Rare Books Conservator. This manuscript has now been saved. But many other seriously damaged and deteriorated manuscripts at Princeton need extensive conservation treatment if they are to survive as well.

You must be logged in to post a comment.