The Manuscripts Division is pleased to announce the acquisition of a letter book of James Monroe (1758-1831), the most recent addition to its substantial Franco-American holdings. Monroe kept the letter book during the first part of his term as American Minister to France, 1794-96. The volume includes 112 letters, probably in the hand of Monroe’s secretary and fellow Virginian Fulwar Skipwith (1765-1838). Many letters have minor textual differences from published versions, including a dozen with previously unrecorded corrections and revisions in Monroe’s own hand, such as his Circular to Consuls and Agents, 25 September 1794 (see below). Eighteen of the letters are unknown and unpublished, including six about American repayment of a loan from the Dutch financiers Willink, Van Staphorst & Hubbard. Monroe was posted to Paris at the height of the French Revolution, only days after the Reign of Terror had ended with the execution of Maximilien Robespierre, Louis-Antoine de Saint-Just, and others. On Sunday, 10 August 1794, Monroe penned his first official letter as U.S. Minister to France, sending political news to Secretary of State Edmund Randolph, a fellow Virginian.

Monroe served with distinction during the Revolutionary War. He crossed the Delaware River with General George Washington on Christmas Day 1776 and a week later was seriously wounded at the Battle of Trenton (2 January 1777). We remember Monroe today for his lifetime of public service, including a term as Senator from Virginia to the U.S. Congress (1790-94); multiple terms as governor of Virginia; Secretary of State (1811-17) and Secretary of War (1814-15) under President James Madison (Princeton Class of 1771); and finally the fifth American President (1817-25). Although a slaveholder, Monroe supported African colonization for free African Americans in the geographical area that eventually became Liberia, for which reason its capital was named Monrovia in his honor. In the Early Republic, he played a major role in U.S. territorial expansion and foreign policy and is best remembered for his promulgation of the Monroe Doctrine (1823).

The Monroe letter book is a large volume with 324 numbered pages. A stationer’s label on front paste down identifies the shop as “À L’Espérance,” located on Rue Neuve des Petits-Champs, facing the French Ministry of Finance. There one could buy quills, ink, paper, sealing wax, and other writing materials, as well as blank volumes like the present letter book. It was a difficult time for Monroe and for Franco-American relations. He found his own position in France undermined by the American adoption of Jay’s Treaty, which the French Directory viewed with suspicion. Among Monroe’s other challenges were the intrigues of “Citizen” Edmond Charles Genêt (1763-1834), the French minister to the United States. Monroe defended his conduct as Minister to France in A View of the Conduct of the Executive in the Foreign Affairs of the United States, Connected with the Mission to the French Republic, during the years 1794, 5, & 6 (Philadelphia: Printed by and for Benjamin Franklin Bache, 1797).

One of Monroe’s principal diplomatic initiatives was securing freedom for American prisoners, the most famous being Thomas Paine (1737-1809), author of Common Sense and The American Crisis. A letter of 1 November 1794 to the French Committee of General Surety was part of Monroe’s successful effort to secure the Paine’s release from Luxembourg prison in Paris, where he worked on The Age of Reason. American citizenship was presented as a reason for Paine’s release. Indeed, he owned a house in Bordentown, New Jersey, and a farm in New Rochelle, New York. Monroe wrote, “The citizens of the United States can never look back to the era of their own revolution without recollecting among the names of their most distinguished patriots that of Thomas Payne. The services that he rendered them in their struggle for liberty have made an impression of gratitude which will never be erased, whilst they continue to merit the character of a just and generous people.”

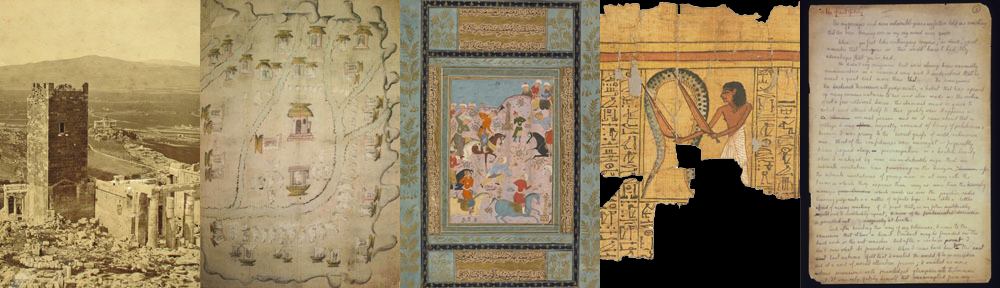

The oldest of the Manuscripts Division’s substantial Franco-American holdings is the correspondence of Raymond de Fourquevaux (1508-1574), French ambassador to Spain, concerning colonization of Florida and the West Indies, 1565-71. This is part of the extensive Americana collection of André De Coppet, Class of 1915 (C0063), who was also the donor of the extensive archives of Eugène de Beauharnais (1781-1824), Napoleon’s step-son and French viceroy in Italy, 1805-14 (C0645). The best-known collection is that of Louis-Alexander Berthier (1753-1815), containing more than a hundred hand-colored, manuscript maps, one of which includes Nassau Hall (C0022). Berthier was an officer on General Rochambeau’s staff and traced the historic overland march of the French and American forces from Philipsburg, New York, to Yorktown, Virginia, in 1781, and then their return march to Boston in 1782. Accompanying these maps is Berthier’s journal in French. Donated by Harry C. Black, Class of 1909, the Berthier maps and journals have been digitized and are available online.

The Manuscripts Division also holds other individual manuscripts and small collections, such as Joachim du Perron, comte de Revel (1756-1814),”Brouillon du journal de ma campagne sur le Languedoc,” 1780-82; Charles Henri d’Estaing (1729-94), “Relation de la compagne navale … en Amérique,” 1778-89; [Comtes de Forbach de Deux-Ponts], “Suite de journal des campagnes 1780, 1781, 1782: dans l’Amérique septentrionale,” 1782; Henri Jean Baptiste de Pontevès-Gien, comte de Pontevès-Gien (1738-90), a journal kept by him as commander of the French naval vessel l’Illustre, 1788-90; Louis-Guillaume Otto, comte de Mosloy, selected correspondence, including a series of letters written to the marquis de Moustier, 1789-91, and two letters received from Michel Guillaume Jean de Crèvecoeur, 1799; and Charles Balthazar Julien Frevret de Saint-Mémin (1770-1852), “Gagne-pain d’un exilé aux États-Unis d’Amérique de 1793 à 1814.” Also dating from this period is a portion of the correspondence of John Lewis [Jean-Louis] Guillemard, 1787-1844, an English aristocrat of French Huguenot ancestry, who lived in Philadelphia in the late 1790s and corresponded with his family and friends about American politics and foreign relations, the British Empire, and the French Revolution (C1492).

Holdings for the nineteenth century include the recently acquired manuscripts of French journalist Frédéric Gaillardet (1808-82), including a partial draft of L’Aristocratie en Amérique and other materials relating to his travels and observations in Louisiana, Mississippi, and other southern states, as well as in Canada and Cuba, 1837-48 (C01519). French interest in the peoples of North America can also be seen in the photographs of Northern Plains Indians in the “Collection Anthropologique” of Prince Roland Bonaparte (C1177). Relevant holdings on Franco-American historical subjects can be found in the Gilbert Chinard Papers (C0671) and Gilbert Chinard Collection of French Historical Material (C0428). The latter includes letters written by the French Consul to Maryland, 1788-1797; and three untitled and undated 18th-century manuscript documents concerning French governance of Louisiana, its cession to Spain in 1762, and subsequent administration by Spain. Chinard was a Franco-American scholar who was Pyne Professor of French at Princeton University, 1937-50, and was also associated with the Institut Français de Washington.

For more information about the James Monroe letter book, contact Don C. Skemer, Curator of Manuscripts, at dcskemer@princeton.edu Concerning manuscript and archival holdings relating to Franco-American historical, diplomatic, and cultural relations, search the Department of Rare Books and Special Collections finding aids website

You must be logged in to post a comment.