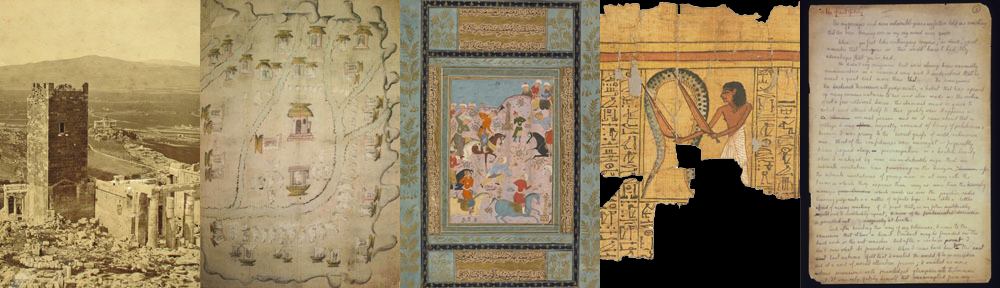

The historic bequest by William H. Scheide (1914-2014), Class of 1936, of the Scheide Library to Princeton has been praised by President Christopher L. Eisgruber as “a defining collection for Firestone Library and Princeton University.” The bequest, including some 2,500 rare books and manuscripts, was the largest single gift to Princeton University in appraised value. But as most people know, Bill Scheide was a generous supporter of libraries beyond his own. We can see this in his gifts to the Manuscripts Division, which are briefly described below. Like the Scheide Library itself, Bill Scheide’s gifts will continue to provide research and instructional opportunities for generations of Princeton faculty and students, as well as visiting researchers.

The John Hinsdale Scheide Collection (C0704). This collection of 7,935 items was amassed in the years 1890-1941 by William T. Scheide (1847-1907) and later by his son John Hinsdale Scheide (1875-1942), Class of 1896–Bill Scheide’s grandfather and father–and originally housed at the family home in Titusville, Pennsylvania. The collection was put on deposit at the Princeton Univesity Library in 1938 and donated by Bill Scheide in 1947. More than half of the items are medieval and Renaissance Italian notarial documents. William T. Scheide acquired most of the contents of the Italian materials in boxes 1-155 from the Florentine publisher and antiquarian book dealer Leo S. Olschki. The collection includes most of the archives of the Benedictine (later Silvestrine) Abbey of S. Vittore delle Chiuse, founded in the late 10th century in the hills overlooking the Italian city of Fabriano, in what is now the province of Marche. John Hinsdale Scheide was far more interested in French and English documents, and bought a great deal from the London dealer Maggs Bros. and at auction. The principal part was acquired at a 1938 auction at Parke-Bernet Galleries, New York. The Slade Collection was described at the time as “about 2500 Chirographical Specimens from the XIIth to XIXth Century” from the collection of Lawrence Slade, who was the son-in-law of the eminent collector Robert Hoe, and had purchased most of them from the Parisian dealer Charavay in the 1920s. The largest number of these documents are part of the family paperrs of the D’Olive family of Toulouse from the 16th century until the French Revolution. For more information about the Scheide Collection, consult the finding aid.

John Hinsdale Scheide Collection of Three Centuries of French History (C0710). This collection contains 386 letters and documents of royalty, nobility, statesmen, and other celebrities of France, from the reign of Louis XII to the commencement of the French Revolution. Famous names in French history represented in the collection include Louis XII, François I, Henri II, Catherine de’ Medici, Charles IX, Henri III, the Duc de Guise, Henri IV, Clement VIII, Louis XIII, Cardinal Richelieu, Louis XIV and his wife Marie Thérèse, Marquise de Maintenon, Jean Baptiste Rousseau, Marquise de Sévigné, Cardinal Mazarin, Louis XV and his wife and daughters, Madame de Pompadour, the Comtesse du Barry, Jean Jacques Rousseau, Voltaire, Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette, Louis XVI, Jacques Necker, the Comte de Mirabeau, and the Marquis de Lafayette. For more information, consult the finding aid.

Princeton Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts (C0931). Scheide was the donor of three manuscripts added to this open collection between 1960 and 1964. Princeton MS. 98, Leonardo Frescobaldi (1324-1405), Viaggio del santissimo sepulcro di Christo, 1493; Princeton MS. 102, Kyrie Eleison with Prosulae, 13th century; Princeton MS. 103, Antiphonary leaf, 14th century. For descriptions, see Don C. Skemer, Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts in the Princeton University Library (2013), vol. 2.

Heinrich Nikolaus Gerber (1702-1775), Musical commonplace book (C0199, no. 423). Gerber was a student of Johann Sebastian Bach at Leipzig and court organist at Sondershausen, 1731-75. He composed music for the clavier, organ, and harp. According to the biographical account by his son, Gerber returned to his home in 1727 and set down many of the things he had learned at Leipzig, as well as his own compositions. Scheide donated the manuscript in 1960.

Interested researchers should contact Public Services, at rbsc@princeton.edu

Alfonso I d’Este, duke of Ferrara (1476-1534),

Illuminated commission for Giovanni Antonio Gozadino,

22 January 1507. (Scheide Documents, box 14, no. 252).

You must be logged in to post a comment.