In 1956, a year before Thomas R. Adams became librarian of the John Carter Brown Library, he queried the university librarian at Princeton about the administration of the rare book collections in the library. The questionnaire was part of a larger survey project resulting in Adams’s article in Library Trends, entitled “Rare Books: Their Influence on the Library World.” (April 1957). Adams’s first five questions were headed “Origins of the Collection.”

Tom Adams was always interested in fundamental questions, such as how and why a collection began. I learned this fact when I worked for him between 1969 and 1974. I was reminded again of this characteristic as I listened to several of his closest personal friends in the profession speak at his memorial this past Saturday.

His last publication appears in the Winter 2008 issue of The Book Collector. It is a valedictory entitled “Defining Americana: The Evolution of the John Carter Brown Library.”

He begins with a remarkable sentence: “The emergence of a rare book library as a research centre had its origins in a reaction to the growth of the tax-supported free public library.” In one swoop, Tom Adams has told us how began the enterprise in which he made his career. His reason fits a larger theme common in collecting – that all collecting is reparative. Thus, one aspect of the ‘rare book library as reseach centre’ was to provide a locus apart from the leveling, ‘best books’ approach provided by an agency of the modern, democratic state. On the other hand, his genesis story can also be considered in terms of changing public policy. Indeed, Adams moves in this direction on page three in his summary story of American libraries. Their roots, he says, lay in the reading publics associated with colleges, churches, or subscriptions ‘companies.’ But as the reading public enlarged in the 19th century, and, concurrently, as did their voting rights and their popular powers to shape public policy, so did ideas about what a library could be. Tax support enabled possession without ownership — the actuality that readers could have a book in their hands independent of the means needed to control it as property.

Adams’s point then is that owners of precious, rare books found such developments alarming because they disabled a system for the future public life of a collector’s books. For these collectors – Adams gives the names on page one: … Peter Force, Thomas Aspinwall, George Brinley, James Lenox, Henry C. Murphy, James Carson Brevoort, Samuel Latham Mitchill Barlow and John Carter Brown — in the days of their youth, the college, church, and company model was in place. There was a certain wholeness in this model. But, by their latter years, and certainly by the early years of their children, a new, mixed, more democratic model was in place. To recover ‘the place of grace’ tracing back to earlier times, it made sense to set up a future apart and anew. In this context, then, we come to the words of John Carter Brown’s son who declared in his will “that this library … shall preserve its identity as a whole” (p. 5)

Although it makes sense to conclude that for Carter Brown’s son, John Nicholas, the phrase “to preserve its individual identity as a whole” meant disunion with the merging democratic tendencies of a Boston Public or a New York Public, there is still the question as to what was meant positively by this phrase. What is a library’s “individual identity”? Can its identity really be independent of the community that shaped it?

I suggest that the John Carter Brown represents an idea comparable to the the idea of the States United. It represents the hope that a singular act will preserve an abstraction — just as it was hoped that a particular declaration made in Philadelphia one past July would bring liberty.

Therein lies the positive meaning of ‘to preserve its individual identity’ — namely, the point of the library was to define, to describe, to help us understand an idea rather than mass-commodify it. ‘The rare book library as a research centre’ is about questions, rather than answers.

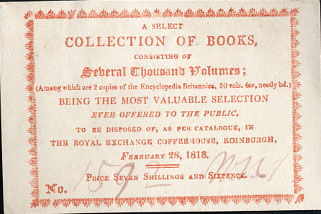

Note: Page citations above are from the reprint of the article whose front cover is pictured above.