1872 • Printers’ Sheet of Miscellaneous Trade Receipts

(“Be gone you pesky old annotations!”)

Might you be curious as to how they had their maps varnished? Or prints cleaned? Or books preserved? Here’s some answers:

For a transcription, go to this link

http://infoshare1.princeton.edu/rbsc2/misc/Bib_4982494.pdf

Call number for:

Crisp, William Finch.

The Printers’ Sheet of Miscellaneous Trade Receipts. Great Yarmouth, [England], [1872.] is

(Ex) Broadside 390.

For other “trade receipts” and “how-to” advice from W. F. Crisp, see the

Internet Archive.

Settle bindings reconsidered

Arms of Morrison impaling Webb covering 1709 Eusebia Triumphans Call number: RHT 17th-773 |

Illustrated here are Settle bindings. Howard Nixon (1909-1983), in his Five Centuries of English Bookbinding, describes these, with some disdain:

“Elkanah settle, who was born in 1640 and had been hailed as a rising playwright in the 1670’s, had dwindled by the end of the century into a hack versifier holding the unremunerative post of ‘City Poet.’ In 1700 he started to work what can only be described as a successful racket, which he carried on for the rest of his life. He composed topical poems, at first on political events and later on more personal subjects such as births, deaths and marriages in the families of the great and wealthy. They were put into leather bindings with elaborate (if not very good) gold tooling embellished with the arms of the likely patron, to whom they were dispatched in hopes of a suitable reward. Should the reward not be forthcoming and the book be returned to Settle, he had the original recipient’s arms covered with a leather only on which were then tooled those of a suitable candidate.”

Settle’s letter of presentation once pinned into a copy of his 1707 Carmen Irenicum inscribed on the title page: “Ex Libris Edwardi Haistwell xvto Cal. Martis 1710.”

“Sir: Be pleased to give me Leave to make you once mre an humble present, on this great subject, the Union of the Two Kingdoms; hoping it may find Your Acceptance from Your most obliged and most humble Servant. E: Settle.”

Call number: RHT 17th-785.

Gathered within them, there is much to analyze, be it social, cultural, or design history. Created as objects for presentation to nobility, they raise many questions surrounding such objects. Recipients range from earls down through the ranks to knights and wealthy merchants. So, why was a particular recipient chosen? Was the present planned to initiate a connection or to sustain one already formed? Did the present result in an exchange for Settle? Did he obtain any remuneration for his art?

One exception to this corner ornament pattern has been found. Covering a 1703 poem, the binding consists of the typical perimeter frame and inner frame ornamented at corners. Rather than the expected flower tool, the corner tool is the thistle. In addition, no arms are present. What can be made of these incongruities? Rather than being a binding made contemporaneous with the imprint it covers, perhaps this is a ‘blank’ prepared ca. 1707 as a trial effort for the new thistle tool.

Why this elimination occurs is only a matter of speculation: perhaps the sparer layout was regarded as more chaste or perhaps removal of the inner frame was intended to focus keener attention on arms of such high rank.

Gallery of images available at

http://www.flickr.com/photos/08544-sf/sets

New acquistion: Vesalius

Special funds available at the end of the fiscal year made possible two major acquisitions: the first and second editions of De humani corporis fabrica by Andreas Vesalius, published 1543 and 1555 respectively. This towering monument in the history of science has long been lacking in the Library’s collections. If Princeton had a medical school, there might have been an early organizational imperative to obtain this work marking the beginning of modern anatomical studies, but the University has no medical school. Growing campus interest in the history of science during the past several decades has involved classroom presentations of original editions of important landmarks of science already held by the Library, such as the De revolutionibus of Copernicus (1543). Those presentations well demonstrated our wealth of such key books in the mathematical and physical sciences, but they also showed up that we lacked the some equally revolutionary work in medicine. These two new acquisitions unquestionably strengthen our ability to bring into the classroom virtually all the monumental works marking the beginning of the modern science during the Renaissance.

Andreas Vesalius, De humani corporis fabrica(Basle, 1543) [Call number: (Ex) QM21 .V418 1543f]. Some notable aspects of this copy: 1) Leaf M3 (“Venarum, arteriarum, nervorumque omnium integra delineatio”) has eight contemporarily-colored figures of organs mounted on recto and verso, providing a three-dimensional perspective of the human anatomical figure. And, 2) bound in contemporary German calf over wooden boards; spine in six compartments; covers show seven vertical rows with alternating motifs of married couple and of lamp flanked by chalices; outer border shows rosettes and floral motifs; vestiges of catches and clasps at fore-edge.

Andreas Vesalius, De humani corporis fabrica(Basle, 1555) [Call number: (Ex) QM21 .V418 1555f]. Bound in 17th century Dutch paneled vellum. Armorial bookplate of Sir William Sterling-Maxwell (1818-1878) on front pastedown; his “Arts of Design” bookplate on back pastedown.

Bindings from the shop of John Bateman, Royal Binder

|

Front cover: arms of George Stuart, |

Spine |

Back cover: arms of George Abbot, Archbishop of Canterbury |

|

Captain John Smith. The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles (London, 1624) [Call number (ExKa) Americana 1624q Smith copy 3]

|

|

Mirjam M. Foot assigns the above binding to the shop of John Bateman, Royal Binder to James I. Cf. The Henry Davis Gift. A Collection of Bookbindings. Volume 1. Studies in the History of Bookbinding, (London, 1982) p. 35-49. This is number 65 (p. 49). She evidently based her attribution on the illustration of the front cover published in the Sotheby’s auction sale catalogue of the books belonging to the Duke of Leeds on June 2-4, 1930. This book was lot 606 and it was purchased by A.S.W. Rosenbach for £1400 who eventually sold it to Grenville Kane to add to his outstanding collection of Americana. In the late 1940s, Princeton purchased the Kane collection. |

|

Finding John Witherspoon’s books

Witherspoon’s books entered the collections of the Library in 1812. They were comingled with the 706 volumes of his son-in-law Samuel Stanhope Smith, purchased for the sum of $1,500. For decades Witherspoon’s books remained distributed within the working book stock of the Library, which totaled 7,000 volumes by 1816. After the Civil War, the surge of interest in leaders of the American Revolution included a focus on Witherspoon. At the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, the Presbyterians erected a statue of Witherspoon. Like his visage, his books were also of interest.

The hunt for the books began during the tenure of Frederick Vinton, librarian from 1873 until his death in 1890. There was no precise list of such. Evidence of ownership was based on two grounds: 1) Witherspoon’s signature and book number at the top of the title page (his usual practice) and 2) mention in the list of books in his son-in-law’s library. Only examination of the books themselves and comparison with the Smith list could affirm ownership.

Vinton recorded his findings on blank pages of an 1814 catalogue of the library. Varnum Lansing Collins, Class of 1893, served as reference librarian from 1895 to 1906. He regularized Vinton’s findings into an alphabetical list, perhaps in preparation for his biography of Witherspoon published in 1925. In the 1940s, during the tenure of librarian and Jefferson scholar Julian Boyd, curator Julie Hudson physically reassembled the Witherspoon books into a separate special collection with the location designator WIT. The project took years, resulting in a collection of more than 300 volumes. In addition to re-gathering the books, Ms Hudson oversaw repairs and rebinding by “Mrs. Weilder and Mr. [Frank] Chiarella of the PEM Bindery” [in New York.]

Since Ms. Hudson’s efforts, a few more Witherspoon books have come to light. During 1949-50, volume one of the third edition of Miscellanea Curiosa (London, 1726) was acquired by exchange. In 1963, Mrs. Frederic James Dennis gave Witherspoon’s copy of The Constitution of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America containing the Confession of Faith, the Catechisms, the Government and Discipline (Philadelphia, 1789), signed by him on the half title. In 1967, the Library purchased Witherspoon’s copy of Thomas Clap’s The Annals or History of Yale College (New Haven, 1766.) In 1978, the Library purchased Witherspoon’s copy of volume one of Jacques Saurin’s Discours historiques, critiques, theologiques, et moraux, sur les evenemens les plus memorables du Vieux, et du Nouveau Testament . (Amsterdam, 1720.) Lastly, there appeared in a 1998 auction in New Hampshire, Witherspoon’s copy of The Odes of Sir Charles Hanbury Williams, Knight of the Bath (London, 1768), however, this was not acquired and its current whereabouts are not known.

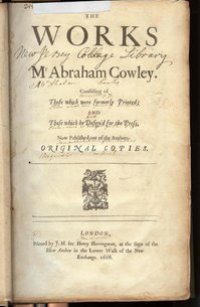

Perhaps if more of Witherspoon’s books are to be found today, then they are to be found in the collections here. This proved the case earlier this week. Now identified as Witherspoon’s is this entry in the Smith catalogue: “Works of Abraham Cowley …. 1 Folio.”

Boss Carnahan [President of Princeton, 1823-1859]Johnny Maclean [Vice-president under Carnahan]Boss Rice [Rev. B. H. Rice, D.D., served in Princeton pulpit, 1833 to 1847], Cooley [Rev. E.F. Cooley], Daniel McCalla, Petin the boot black, Moses Hunter, Albert Ribbenbach [?], Old Quackenboth (Uncle Joe), Buddy Be Dash, Catling Ross [?], Goose Leg.

Cartographies of Time • Exhibition on view, June 25 to September 18, 2011 at the Art Museum of Princeton University

WHAT DOES HISTORY LOOK LIKE? How do you map time? In this exhibition, historians Daniel Rosenberg and Anthony Grafton–drawing from their celebrated book, Cartographies of Time: A History of the Timeline– explore the emergence of modern visions of history through graphic representation. Rarely viewed books, manuscripts, charts, and other ingenious devices– drawn primarily from the Department of Rare Books and Special Collections of the Princeton University Library–illustrate a history of visual innovation that stretches from the manuscripts of late medieval Europe through the rise of modern print technologies.

Cartographies of Time focuses on the mutually influential developments of historical thought and graphics, highlighting the emergence of the timeline as both a graphic and an imaginative tool. The works exhibited follow a kind of timeline of their own, beginning with a medieval scroll listing the kings of France and England. Such genealogical scrolls emphasized the continuity of families, sometimes from the creation of the world. But, as the exhibition demonstrates, by the beginning of the sixteenth century, chronologists were experimenting with new and rediscovered graphic forms.

Among early European forms, the tabular grid– a reinterpretation of the model promoted by the Roman Christian theologian Eusebius–was preeminent. Early modern chronologists also borrowed from theological allegory, as in the illustration to Lorenz Faust’s An Anatomy of Daniel’s Statue (1585), where the rulers of four monarchies are inscribed within the image of the biblical king of Babylon. [Illustrated at right.] In addition, sixteenth- and seventeenth-century chronologists relied on the work of astronomers to provide reliable dating; striking chronological graphics–such as those in the magnificent Astronomicum Caesareum (1540) by Petrus Apianus– integrate astronomical and historical data.

By the eighteenth century, chronologists thought it logical that time, like space, could be measured and mapped in an intuitive visual format, and a powerful new visual vocabulary for history emerged, emphasizing an analogy between historical time and the measured line. In the 1750s and 1760 scholars published timelines rigorously measured to scale.

But while these new linear timelines quickly became ubiquitous, and their productions were often strikingly beautiful, historians continued to experiment with novel systems of reference and mnemonics. Stunning examples include a hand-colored chart designed by the Austrian chronologist Frederich Strass (1804), depicting world history as a series of flowing rivers, and one devised by the American educator Emma Willard in 1846, representing historical time as a Greek temple.

Still, this diversity only made clearer the visual force of the measured, linear timeline, which had become embedded in European and American historical consciousness. In the twentieth century it became usual to speak of “timelines” in reference to historical events themselves, not only their graphic representations. The timeline had become a tool of imagination as well as of information graphics.

The “People’s Charter”: a new acquisition

People’s Charter, An Act to provide for the just Representation of the People of Great Britain & Ireland in the Commons’ House of Parliament. London, Whiting (Printer) (1839) [Call number: (Ex) Oversize 2010-0068Q] Broadside, overall 20” x 20”, decorative border and text printed entirely in red, in 6 columns. Broadside has been in scrap album with part of brown guard still attached. In pencil at upper right: “Presented to the Commons by T.W. Attwood”

The “People’s Charter” was of major importance in the attempt to reform Parliament and obtain suffrage for men. Early in 1838 a group of the newly formed Chartists (one of the first working class movements in the world) met and decided to draft a document known as the “People’s Charter” which took the form of a Parliamentary Bill. It’s draughtsmen were William Lovett, secretary of the London Working Men’s Association, and Francis Place, a Charing Cross tailor. The Charter contained 6 demands: 1. Universal suffrage for men over 21. 2. Equal sized electoral distribution. 3. Voting by secret ballot. 4. End of property qualification for Parliament. 5. Payment for M.P’s 6. Annual election of Parliament. It was presented to Parliament by Thomas Attwood but suffered rejection. However the seeds of discontent were sown and after a period of meetings and riots the objects of their demands were mostly met.

Sold in New York in 1838; now on the Library’s shelves

One lot, number 537, “Biblia Germanica, wood cuts, 2 vol. fol. 1490,” eventually found its way to the shelves of the Princeton University Library. Its confirmed year of arrival is 1916. Where was the Bible between 1838 and 1916?

A ten page memorandum accompanying the Bible provides some answers. Minister of Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church in New York, the Rev. Dr. James Waddell Alexander (1804-1859), tells us in “Some Account of an Old Bible in the Hands of William Scott” that in 1856 it was owned by parishioner William Scott, who, other sources tell us, was said to be a friend and cousin of Sir Walter Scott, as well as a trustee of New York’s North Moore Street Public School. It is unclear how and why William Scott came to possess the Bible, but marks of both previous owners and the book trade clearly show that the Bible belonged to George Kloss, appeared as lot 748 in his 1835 London sale, and later appeared as lot 537 in the 1838 New York sale.

The link between William Scott and Princeton is Scott’s grandson, Laurence Hutton, who was a successful New York literary figure. Hutton relocated to Princeton in the 1890s, one of a several like-minded literary men who purposefully settled in town during that decade. Hutton owned this Bible and after he died in 1904, many of his books were shelved in the Exhibition Room of the Library. According to a 1916 account, they were part of “the Hutton Memorial Collection, consisting of several hundred books, autographed portraits, paintings, etc., from the library of the late Laurence Hutton, A.M. This collection was left by Mr. Hutton to trustees to be put in some safe place for a permanent memorial and was presented by them to the University.”

Library markings inside the Bible as well as catalogue records show that it remained part of the Hutton Memorial until about the 1930s, at which time it was re-classified so as to become part of the general collection of incunabula coded ‘ExI.’ It remains in the ‘ExI’ class down to today.

The Rev. Dr. Alexander’s memorandum is a remarkable document in its own right because it gives us a sense of the state of book history knowledge in the 19th century. Such evidence still remains scattered among a number of sources: trade journals, such as Joseph Sabin’s American Bibliopolist; major city newspapers; accounts published in larger works, such as Isaiah Thomas’s paragraphs in his History of Printing in America on an incunable Bible owned by the Mather family; as well as manuscripts in archives and other repositories.

A transcription of the memorandum follows:

Some Account of an Old Bible in hands of Wm Scott.

By Revd Dr. J.W. Alexander (Copy)

Another Old Bible

From time to time the newspapers give accounts of ancient printed Bibles. Our own columns have contained numerous statements of this kind; and we now add another, in a communication with which the Rev. Dr. Alexander of this city has favoured us at our request.

New York Feb. 1856

Rev. and Dear Sir.

The first part of a German Bible, belonging, to a worthy member of my charge, is probably unique in this country, and, as I observe by the books, is rare even in Europe. As you desire information respecting it, you will allow me to add a few statements concerning similar editions.

The old volume, which belongs to my esteemed friend, WM Scott Esq, has lost three leaves, including the title page, but is otherwise in excellent condition. It is bound in vellum, and has that remarkable brilliancy of ink, and depth of impression, which are matter of wonder in Early printing. The folios, (strictly so called, as that they are leaves, and not pages) are numbered, the last being 503. It contains the first part only that is from Genesis to Psalms, inclusively. The illuminated capitals are imitation of those which adorned manuscripts; the gilding and colours of these are well preserved. The coarse woodcuts are also highly coloured. The second page, or first after the title, begins with a German version of St Jerome’s Epistle to Paulines, introductory to the historical books. In the middle parts the paper is clean, and well kept. The exterior leaves are soiled, but here and there carefully repaired by insertions. The names of three former possessors, are very distinct, viz:

1. 1. In manuscript, “G.A. Michel, V.D.M.”

2. 2. On a ticket, under an engraved coat of arms “Matthias Jacob Adam Steiner.”

3. 3. On a ticket, “Georgius A. Klotz M.D. Francofurt ad Moenum.” Some owners, probably more recent than any of these, but long ago, as the faded ink shows have written the following bibliographical notes on the inside of the first cover, and the opposite fly leaf. From conjecture as to the age of the several entries, I arrange them thus, though their position is different, on the pages. (Translated.) “A defective part of a very uncommon, rare, and extremely, scarce Bible. I bought the same in 1772 from a book peddler for 24 gr. Still it remains a treasure and ornament of the library.”

2. 2. (Same hand.) In margin “I, 1785”, and then, “It appears to be an edition of the Bible, which on a/c of its iluminated figures was named the renowned or princely work (das durchlauchtige work;) and to have been printed in one thousand four hundred and eighty three, or eighty eight. (1483 or 1488.) Compare Hageman on Translations of the SS. page 263. Baumgartens Notices of remarkable books PI pp 97-101. Solgen Bible PI p.9. Schwartz part II p. 199.”

3. 3. (Same hand.) ” Concerning a translation of the Bible near the close of the fifteenth century, see Blaufus, Contributions to an acquatance with rare books, Vol. 1 p. 109.

4. 4. (In another hand.) “It appears to be a part of that rare and uncommon bible, which was printed in small-folio at Strasburg, without the printer’s house in fourteen hundred eighty five (1485.) (In margin, “A mistake, see preceding page.”) Vide Panzer, Literary Notices of the very oldest printed German Bibles, page 71, the X. m (sic)

5. 5, (Probably the same hand as the last.)

“From Panzer’s Extended description of the oldest Augsburg Editions of the Bible, p. 29 XII, it appears that this is certainly the first part of that German Bible which was printed at Augsburg in fourteen hundred and ninety, (1490) by Hans Schönsperger, in small-folios. For all the distinctive marks of this edition of Schönsperger which are there given, correspond most exactly with this copy.”

6. 6. (Another hand partly overrunning the ticket with Steiner’s name and arms.) “Panzers German Annals. T182, 285.

¶1ST Part

¶Twelfth complete German Edition of the Bible, Augsburg, Hans Schönsperger 1490.”

7. 7. (In pencil) “Wanting title page to fol 80 to 107.” (which corresponds with the fact.)

From the notes it is evident that this fine old volume though but a moiety, was considered highly valuable at least half a century ago. Panzer, who is several times cited above, is the celebrated Bibliographer of Nuremburg, who died in 1804, at a very great age. He devoted himself to the subject of Bible-Editions, and made a costly collection of these, which in 1780 passed into the hands of one of the Dukes of Wurtemburg. He published (1783 and 1791). “Outlines of a complete History of Luther’s version, from, 1517- 1581.” Two, at least, of Panzer’s more general works, are in the Astor Library. The vulgar error that there was no German translation before that of Luther should be corrected. The first that is certainly known, is that of the Vienna Library, and was made about 1466. (Montfaucon, a/c “Bible of Every Land p. 175.) Several authorities concur in staking the number of printed editions of the German Bible before Luther as fourteen in High German, and three in Low German. (Pischon , Einladungs, Schrift, & c. Berlin 1834).

To my friend and co-presbyter, Rev. Fred Steins of this city, I am indebted for the reference to Pischon below, as also for an extract from manuscript notes made by himself on the lectures of Professor Delbrück at the University of Bonn, in 1827, which was thus:

There were German Bibles before Luther, of which Panzer enumerates fourteen. From Panzen himself, we glean the following notice; The twelfth edition Augsburg, 1490, printed by Hans Schönperger, first part ends with Psalms, contains 503 Folios. (Annals, Vol.1.p.182.) Before the year 1578, there were only fourteen complete editions of the Bible in German, (p.9 & 99). Of these the first is the Mentz Bible, 1462, by Fust and Schöffer.

The first, with date on the title, is the sixth edition, fol. Augsburg, 1477. All these editions are described in Panzer’s Annals, a work which is in the Astor Library.

Before closing this dry and tedious letter, which may gratify one or two booksworms and collectors, let me say a word or two about the inside of the volume. It contains more than 70 woodcuts illustrative of the text, and, most significant in respect to the arts. Each of these extends across the page, occupying about one third of the letter press.

The Supreme Being is repeatedly delineated, under the figure of an old man. The cuts are highly colored. The patriarchs and prophets are represented in the garb of the fifteenth century, with tight hose, and pointed shoes. Jacob’s ladder is reared beside a lake or river, with quite a swell of waves, and a boat. Moses has the horns always accorded to him by Catholic and Medieval art. Naaman washes in Jordan, while a German carriage and pair, with pastillion, await him on the bank. Not far from a Gothic Castle, Queen Esther is attended by train-bearers, with middle-age coiffure. The pigment in every instance, is laid on boldly. In a word, the pictorial part is precisely in the manner of a clever child, handling his first paint box. This curious specimen of typography has now passed out of my hands, but I have supposed that as so much is said of volumes a century younger than this, you would have patience with some a/c of a pictorial Bible three hundred and fifty six years old. (In 1856).

I am very truly

Your friend and servant

James W. Alexander

(Copy)

Call number for 1856 memorandum:

C0323 Alexander Family Collection • Box 2, Folder 13

Example of illustrations:

Reform Catechism

Reform Catechism. To which is added the Important Clause in the Reform Act; inasmuch, as it tends to deprive Nine-tenths of the People of their Elective Franchise. [London] T. Birt, 39 Great St. Andrew Street, Seven Dials [1832 / 1833] [Call number: (Ex) Item 5987680]

This broadside evokes the term ‘imprint’ in two senses. On the one hand, there is the inky fingerprint adjacent to the printer’s name. Could this be Thomas Birt’s own?

On the other hand, we are reminded of the fervor of democratic reform, nowadays appearing on the front pages of our newspapers. Even though the Reform Act of 1832 broadened representation in Parliament and enlarged the franchise, there was still discontent because of an exclusion clause. No vote was allowed to the many owning or tenant in properties valued under £10.

According to his other publications, Thomas Birt maintained a “wholesale and retail Song and Ballad Warehouse” and further declared “Country orders punctually attended to. Every description of printing on reasonable terms. Children’s books, battledores, pictures, &c.”