By Catherine Zandonella, Office of the Dean for Research

Just as a global positioning system (GPS) helps find your location, the brain has an internal system for helping determine the body’s location as it moves through its surroundings.

A new study from researchers at Princeton University provides evidence for how the brain performs this feat. The study, published in the journal Nature, indicates that certain position-tracking neurons — called grid cells — ramp their activity up and down by working together in a collective way to determine location, rather than each cell acting on its own as was proposed by a competing theory.

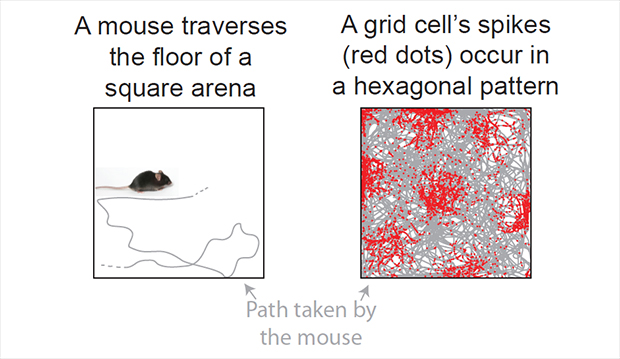

Grid cells are neurons that become electrically active, or “fire,” as animals travel in an environment. First discovered in the mid-2000s, each cell fires when the body moves to specific locations, for example in a room. Amazingly, these locations are arranged in a hexagonal pattern like spaces on a Chinese checker board. (See figure.)

“Together, the grid cells form a representation of space,” said David Tank, Princeton’s Henry L. Hillman Professor in Molecular Biology and leader of the study. “Our research focused on the mechanisms at work in the neural system that forms these hexagonal patterns,” he said. The first author on the paper was graduate student Cristina Domnisoru, who conducted the experiments together with postdoctoral researcher Amina Kinkhabwala.

Domnisoru measured the electrical signals inside individual grid cells in mouse brains while the animals traversed a computer-generated virtual environment, developed previously in the Tank lab. The animals moved on a mouse-sized treadmill while watching a video screen in a set-up that is similar to video-game virtual reality systems used by humans.

She found that the cell’s electrical activity, measured as the difference in voltage between the inside and outside of the cell, started low and then ramped up, growing larger as the mouse reached each point on the hexagonal grid and then falling off as the mouse moved away from that point.

This ramping pattern corresponded with a proposed mechanism of neural computation called an attractor network. The brain is made up of vast numbers of neurons connected together into networks, and the attractor network is a theoretical model of how patterns of connected neurons can give rise to brain activity by collectively working together. The attractor network theory was first proposed 30 years ago by John Hopfield, Princeton’s Howard A. Prior Professor in the Life Sciences, Emeritus.

The team found that their measurements of grid cell activity corresponded with the attractor network model but not a competing theory, the oscillatory interference model. This competing theory proposed that grid cells use rhythmic activity patterns, or oscillations, which can be thought of as many fast clocks ticking in synchrony, to calculate where animals are located. Although the Princeton researchers detected rhythmic activity inside most neurons, the activity patterns did not appear to participate in position calculations.

Domnisoru, Cristina, Amina A. Kinkhabwala & David W. Tank. 2013. Membrane potential dynamics of grid cells. Nature. doi:10.1038/nature11973. Published online Feb. 10, 2013.

This work was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke under award numbers 5RC1NS068148-02 and 1R37NS081242-01, the National Institute of Mental Health under award number 5R01MH083686-04, a National Institutes of Health Postdoctoral Fellowship grant F32NS070514-01A1 (A.A.K.), and a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (C.D.).

You must be logged in to post a comment.