By John Greenwald, Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory

Among the top puzzles in the development of fusion energy is the best shape for the magnetic facility — or “bottle” — that will provide the next steps in the development of fusion reactors. Leading candidates include spherical tokamaks, compact machines that are shaped like cored apples, compared with the doughnut-like shape of conventional tokamaks. The spherical design produces high-pressure plasmas — essential ingredients for fusion reactions — with relatively low and cost-effective magnetic fields.

A possible next step is a device called a Fusion Nuclear Science Facility (FNSF) that could develop the materials and components for a fusion reactor. Such a device could precede a pilot plant that would demonstrate the ability to produce net energy.

Spherical tokamaks as excellent models

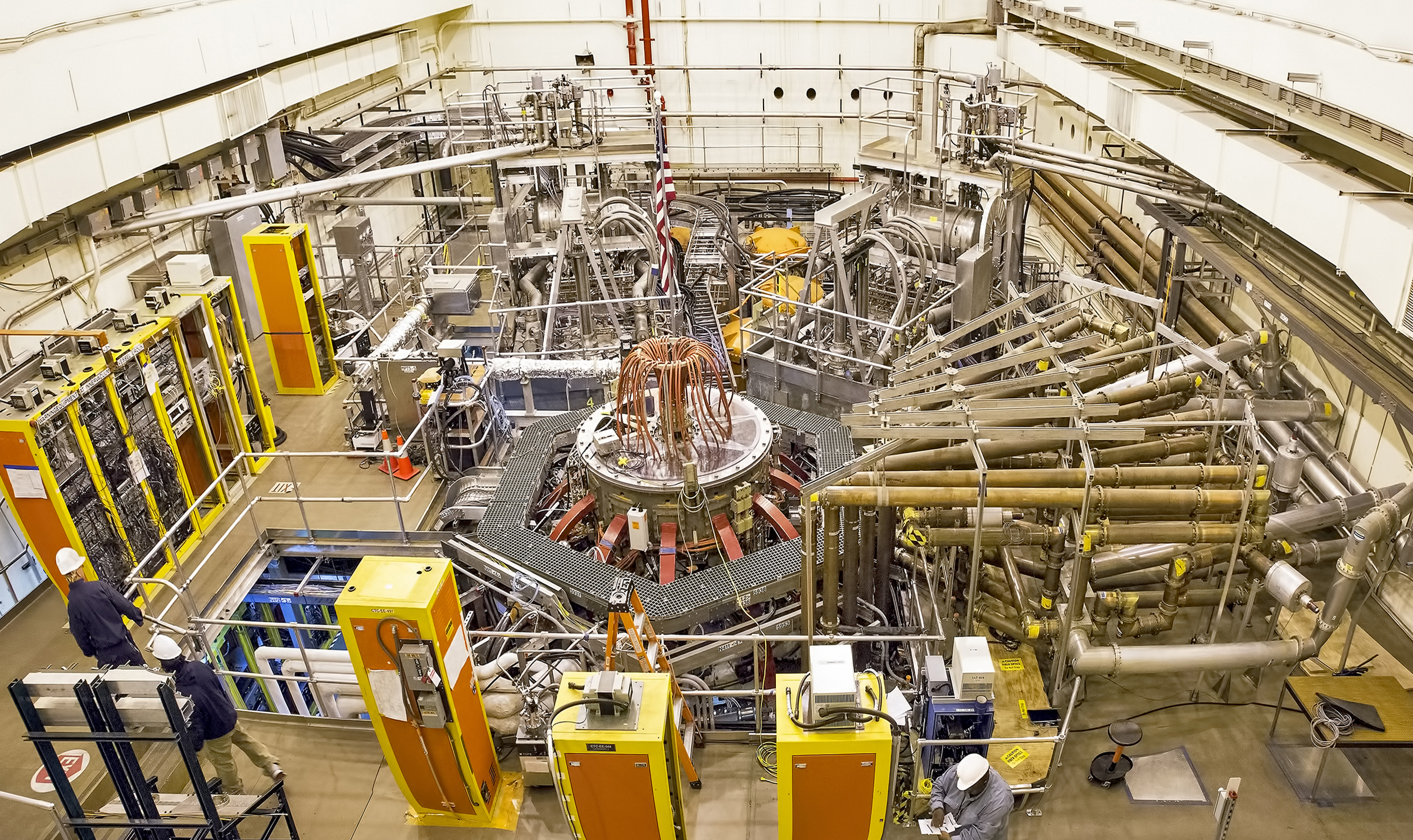

Spherical tokamaks could be excellent models for an FNSF, according to a paper published online in the journal Nuclear Fusion on August 16. The two most advanced spherical tokamaks in the world today are the recently completed National Spherical Torus Experiment-Upgrade (NSTX-U) at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL), which is managed by Princeton University, and the Mega Ampere Spherical Tokamak (MAST), which is being upgraded at the Culham Center for Fusion Energy in the United Kingdom.

“We are opening up new options for future plants,” said Jonathan Menard, program director for the NSTX-U and lead author of the paper, which discusses the fitness of both spherical tokamaks as possible models. Support for this work comes from the DOE Office of Science.

The 43-page paper considers the spherical design for a combined next-step bottle: an FNSF that could become a pilot plant and serve as a forerunner for a commercial fusion reactor. Such a facility could provide a pathway leading from ITER, the international tokamak under construction in France to demonstrate the feasibility of fusion power, to a commercial fusion power plant.

A key issue for this bottle is the size of the hole in the center of the tokamak that holds and shapes the plasma. In spherical tokamaks, this hole can be half the size of the hole in conventional tokamaks. These differences, reflected in the shape of the magnetic field that confines the superhot plasma, have a profound effect on how the plasma behaves.

Designs for the Fusion Nuclear Science Facility

First up for a next-step device would be the FNSF. It would test the materials that must face and withstand the neutron bombardment that fusion reactions produce, while also generating a sufficient amount of its own fusion fuel. According to the paper, recent studies have for the first time identified integrated designs that would be up to the task.

These integrated capabilities include:

- A blanket system able to breed tritium, a rare isotope — or form — of hydrogen that fuses with deuterium, another isotope of the atom, to generate the fusion reactions. The spherical design could breed approximately one isotope of tritium for each isotope consumed in the reaction, producing tritium self-sufficiency.

- A lengthy configuration of the magnetic field that vents exhaust heat from the tokamak. This configuration, called a “divertor,” would reduce the amount of heat that strikes and could damage the interior wall of the tokamak.

- A vertical maintenance scheme in which the central magnet and the blanket structures that breed tritium can be removed independently from the tokamak for installation, maintenance, and repair. Maintenance of these complex nuclear facilities represents a significant design challenge. Once a tokamak operates with fusion fuel, this maintenance must be done with remote-handling robots; the new paper describes how this can be accomplished.

For pilot plant use, superconducting coils that operate at high temperature would replace the copper coils in the FNSF to reduce power loss. The plant would generate a small amount of net electricity in a facility that would be as compact as possible and could more easily scale to a commercial fusion power station.

High-temperature superconductors

High-temperature superconductors could have both positive and negative effects. While they would reduce power loss, they would require additional shielding to protect the magnets from heating and radiation damage. This would make the machine larger and less compact.

Recent advances in high-temperature superconductors could help overcome this problem. The advances enable higher magnetic fields, using much thinner magnets than are presently achievable, leading to reduction in the refrigeration power needed to cool the magnets. Such superconducting magnets open the possibility that all FNSF and associated pilot plants based on the spherical tokamak design could help minimize the mass and cost of the main confinement magnets.

For now, the increased power of the NSTX-U and the soon-to-be-completed MAST facility moves them closer to the capability of a commercial plant that will create safe, clean and virtually limitless energy. “NSTX-U and MAST-U will push the physics frontier, expand our knowledge of high temperature plasmas, and, if successful, lay the scientific foundation for fusion development paths based on more compact designs,” said PPPL Director Stewart Prager.

Twice the power and five times the pulse length

The NSTX-U has twice the power and five times the pulse length of its predecessor and will explore how plasma confinement and sustainment are influenced by higher plasma pressure in the spherical geometry. The MAST upgrade will have comparable prowess and will explore a new, state-of-the art method for exhausting plasmas that are hotter than the core of the sun without damaging the machine.

“The main reason we research spherical tokamaks is to find a way to produce fusion at much less cost than conventional tokamaks require,” said Ian Chapman, the newly appointed chief executive of the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority and leader of the UK’s magnetic confinement fusion research program at the Culham Science Center.

The ability of these machines to create high plasma performance within their compact geometries demonstrates their fitness as possible models for next-step fusion facilities. The wide range of considerations, calculations and figures detailed in this study strongly support the concept of a combined FNSF and pilot plant based on the spherical design. The NSTX-U and MAST-U devices must now successfully prototype the necessary high-performance scenarios.

J.E. Menard, T. Brown, L. El-Guebaly, M. Boyer, J. Canik, B. Colling, R. Raman, Z. Wang, Y. Zhai,P. Buxton, B. Covele, C. D’Angelo, A. Davis, S. Gerhardt, M. Gryaznevich, M. Harb, T.C. Hender,S. Kaye, D. Kingham, M. Kotschenreuther, S. Mahajan, R. Maingi, E. Marriott, E.T. Meier, L. Mynsberge, C. Neumeyer, M. Ono, J.-K. Park, S.A. Sabbagh, V. Soukhanovskii, P. Valanju and R. Woolley. Fusion nuclear science facilities and pilot plants based on the spherical tokamak. Nucl. Fusion 56 (2016) — Published 16 August 2016.

PPPL, on Princeton University’s Forrestal Campus in Plainsboro, N.J., is devoted to creating new knowledge about the physics of plasmas — ultra-hot, charged gases — and to developing practical solutions for the creation of fusion energy. Results of PPPL research have ranged from a portable nuclear materials detector for anti-terrorist use to universally employed computer codes for analyzing and predicting the outcome of fusion experiments. The Laboratory is managed by the University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science, which is the largest single supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

You must be logged in to post a comment.