By John Greenwald, Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory Communications

Among the intriguing issues in plasma physics are those surrounding X-ray pulsars — collapsed stars that orbit around a cosmic companion and beam light at regular intervals, like lighthouses in the sky. Physicists want to know the strength of the magnetic field and density of the plasma that surrounds these pulsars, which can be millions of times greater than the density of plasma in stars like the sun.

Researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) have developed a theory of plasma waves that can infer these properties in greater detail than in standard approaches. The new research analyzes the plasma surrounding the pulsar by coupling Einstein’s theory of relativity with quantum mechanics, which describes the motion of subatomic particles such as the atomic nuclei — or ions — and electrons in plasma. Supporting this work is the DOE Office of Science.

Quantum field theory

The key insight comes from quantum field theory, which describes charged particles that are relativistic, meaning that they travel at near the speed of light. “Quantum theory can describe certain details of the propagation of waves in plasma,” said Yuan Shi, a graduate student at Princeton University in the Department of Astrophysics’ Princeton Program in Plasma Physics, and lead author of a paper published July 29 in the journal Physical Review A. Understanding the interactions behind the propagation can then reveal the composition of the plasma.

Shi developed the paper with assistance from co-authors Nathaniel Fisch, director of the Princeton Program in Plasma Physics and professor and associate chair of astrophysical sciences at Princeton University, and Hong Qin, a physicist at PPPL and executive dean of the School of Nuclear Science and Technology at the University of Science and Technology of China. “When I worked out the mathematics they showed me how to apply it,” said Shi.

In pulsars, relativistic particles in the magnetosphere, which is the magnetized atmosphere surrounding the pulsar, absorb light waves, and this absorption displays peaks. “The question is, what do these peaks mean?” asks Shi. Analysis of the peaks with equations from special relativity and quantum field theory, he found, can determine the density and field strength of the magnetosphere.

Combining physics techniques

The process combines the techniques of high-energy physics, condensed matter physics, and plasma physics. In high-energy physics, researchers use quantum field theory to describe the interaction of a handful of particles. In condensed matter physics, people use quantum mechanics to describe the states of a large collection of particles. Plasma physics uses model equations to explain the collective movement of millions of particles. The new method utilizes aspects of all three techniques to analyze the plasma waves in pulsars.

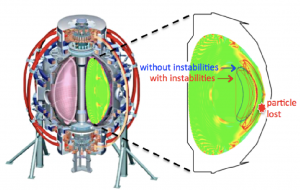

The same technique can be used to infer the density of the plasma and strength of the magnetic field created by inertial confinement fusion experiments. Such experiments use lasers to ablate — or vaporize —a target that contains plasma fuel. The ablation then causes an implosion that compresses the fuel into plasma and produces fusion reactions.

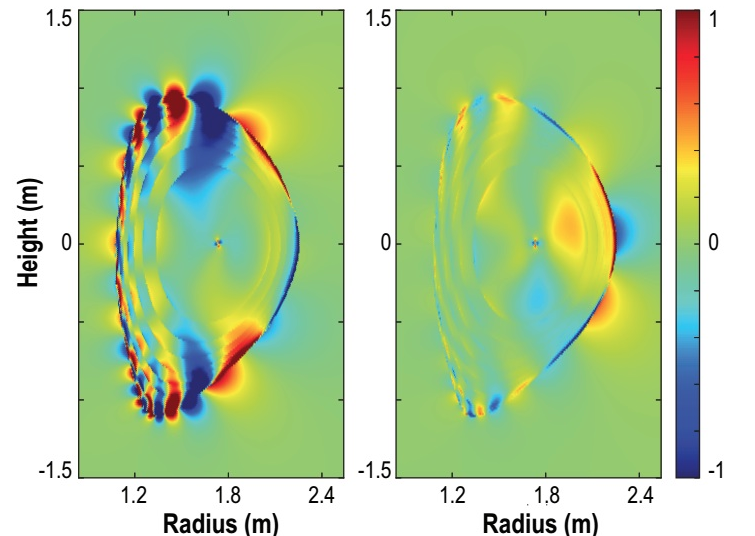

Standard formulas give inconsistent answers

Researchers want to know the precise density, temperature and field strength of the plasma that this process creates. Standard mathematical formulas give inconsistent answers when lasers of different color are used to measure the plasma parameters. This is because the extreme density of the plasma gives rise to quantum effects, while the high energy density of the magnetic field gives rise to relativistic effects, says Shi. So formulations that draw upon both fields are needed to reconcile the results.

For Shi, the new technique shows the benefits of combining physics disciplines that don’t often interact. Says he: “Putting fields together gives tremendous power to explain things that we couldn’t understand before.”

Yuan Shi, Nathaniel J. Fisch, and Hong Qin. Effective-action approach to wave propagation in scalar QED plasmas. Phys. Rev. A 94, 012124 – Published 29 July 2016.

PPPL, on Princeton University’s Forrestal Campus in Plainsboro, N.J., is devoted to creating new knowledge about the physics of plasmas — ultra-hot, charged gases — and to developing practical solutions for the creation of fusion energy. Results of PPPL research have ranged from a portable nuclear materials detector for anti-terrorist use to universally employed computer codes for analyzing and predicting the outcome of fusion experiments. The Laboratory is managed by Princeton University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science, which is the largest single supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit science.energy.gov.

You must be logged in to post a comment.