By John Greenwald, Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory Communications

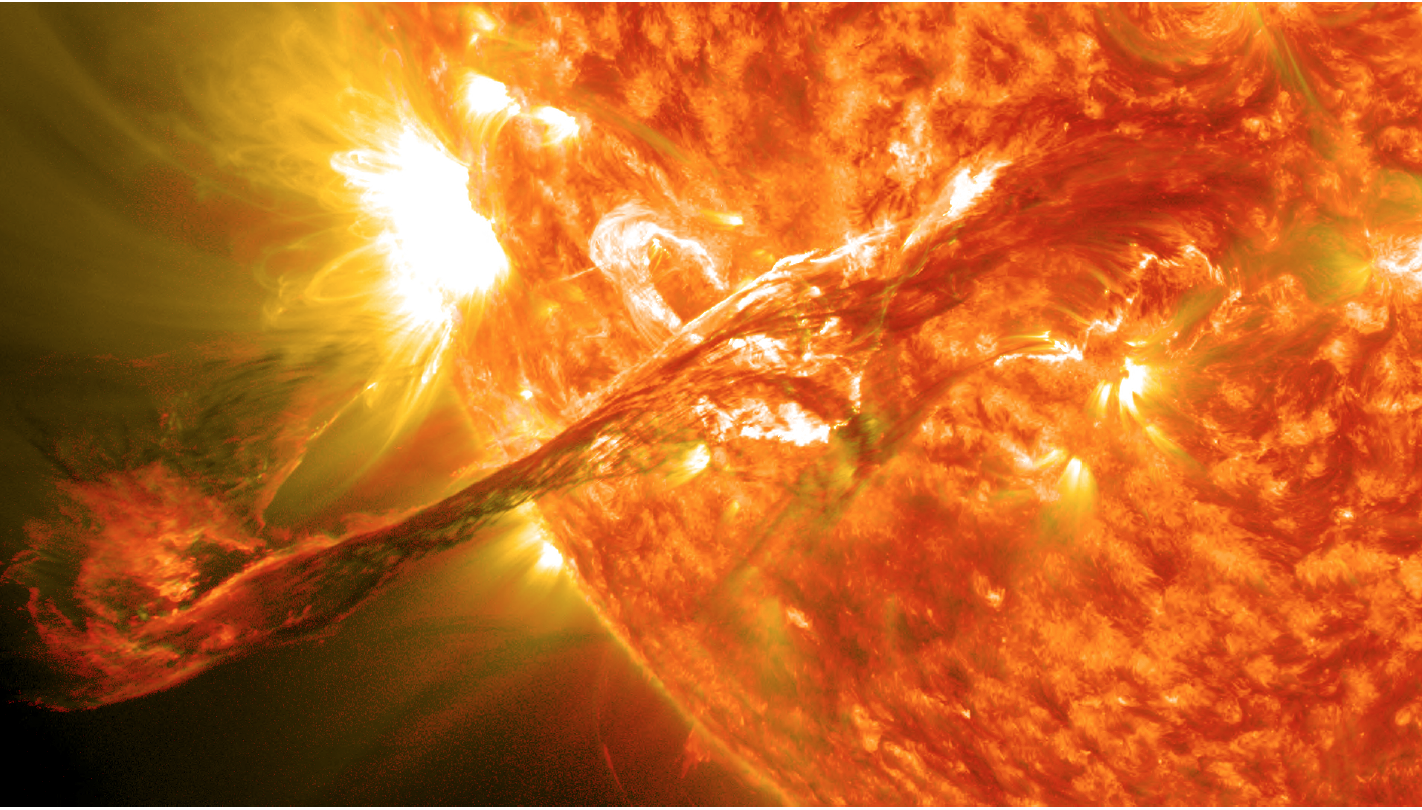

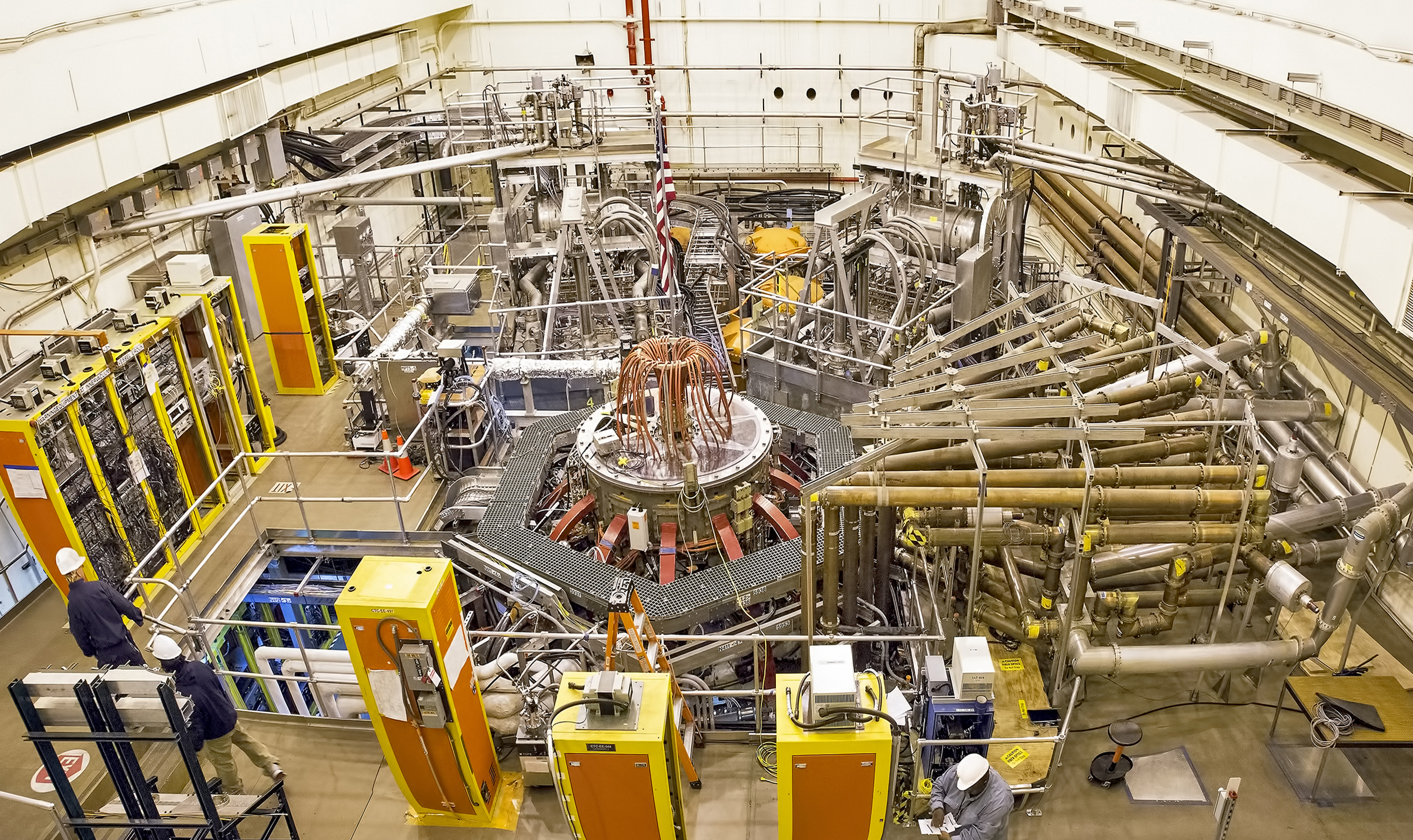

Scientists have proposed a groundbreaking solution to a mystery that has puzzled physicists for decades. At issue is how magnetic reconnection, a universal process that sets off solar flares, northern lights and cosmic gamma-ray bursts, occurs so much faster than theory says should be possible. The answer, proposed by researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) and Princeton University, could aid forecasts of space storms, explain several high-energy astrophysical phenomena, and improve plasma confinement in doughnut-shaped magnetic devices called tokamaks designed to obtain energy from nuclear fusion.

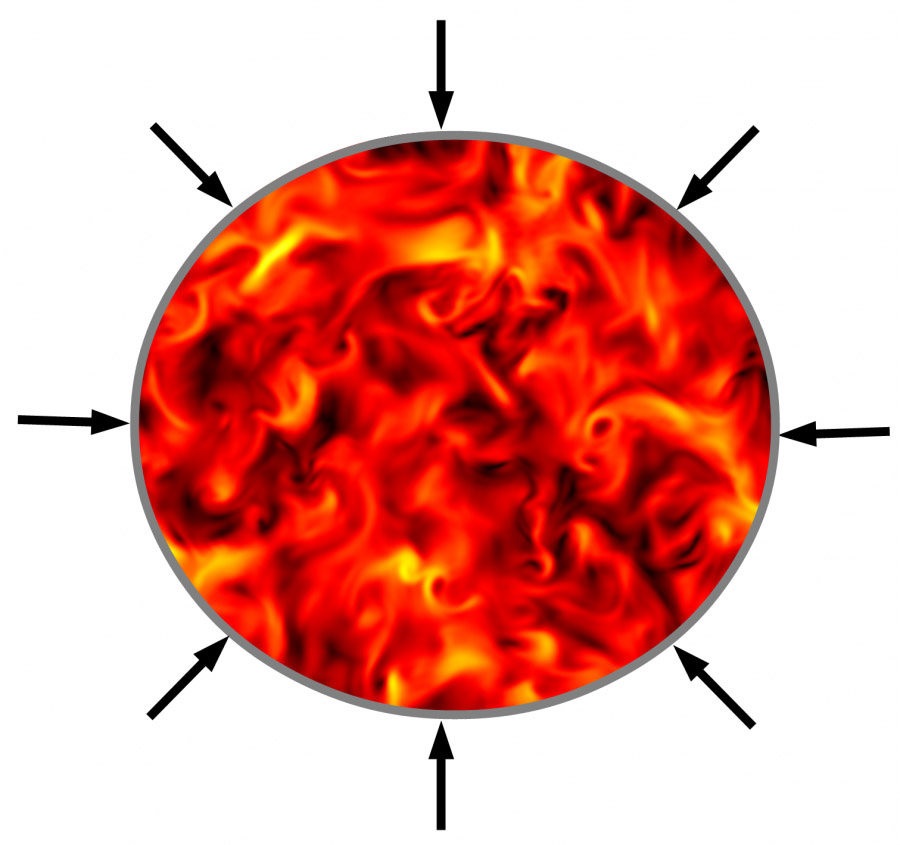

Magnetic reconnection takes place when the magnetic field lines embedded in a plasma — the hot, charged gas that makes up 99 percent of the visible universe — converge, break apart and explosively reconnect. This process takes place in thin sheets in which electric current is strongly concentrated.

According to conventional theory, these sheets can be highly elongated and severely constrain the velocity of the magnetic field lines that join and split apart, making fast reconnection impossible. However, observation shows that rapid reconnection does exist, directly contradicting theoretical predictions.

Detailed theory for rapid reconnection

Now, physicists at PPPL and Princeton University have presented a detailed theory for the mechanism that leads to fast reconnection. Their paper, published in the journal Physics of Plasmas in October, focuses on a phenomenon called “plasmoid instability” to explain the onset of the rapid reconnection process. Support for this research comes from the National Science Foundation and the DOE Office of Science.

Plasmoid instability, which breaks up plasma current sheets into small magnetic islands called plasmoids, has generated considerable interest in recent years as a possible mechanism for fast reconnection. However, correct identification of the properties of the instability has been elusive.

The Physics of Plasmas paper addresses this crucial issue. It presents “a quantitative theory for the development of the plasmoid instability in plasma current sheets that can evolve in time” said Luca Comisso, lead author of the study. Co-authors are Manasvi Lingam and Yi-Min Huang of PPPL and Princeton, and Amitava Bhattacharjee, head of the Theory Department at PPPL and Princeton professor of astrophysical sciences.

Pierre de Fermat’s principle

The paper describes how the plasmoid instability begins in a slow linear phase that goes through a period of quiescence before accelerating into an explosive phase that triggers a dramatic increase in the speed of magnetic reconnection. To determine the most important features of this instability, the researchers adapted a variant of the 17th century “principle of least time” originated by the mathematician Pierre de Fermat.

Use of this principle enabled the researchers to derive equations for the duration of the linear phase, and for computing the growth rate and number of plasmoids created. Hence, this least-time approach led to a quantitative formula for the onset time of fast magnetic reconnection and the physics behind it.

The paper also produced a surprise. The authors found that such relationships do not reflect traditional power laws, in which one quantity varies as a power of another. “It is common in all realms of science to seek the existence of power laws,” the researchers wrote. “In contrast, we find that the scaling relations of the plasmoid instability are not true power laws – a result that has never been derived or predicted before.”

PPPL, on Princeton University’s Forrestal Campus in Plainsboro, N.J., is devoted to creating new knowledge about the physics of plasmas — ultra-hot, charged gases — and to developing practical solutions for the creation of fusion energy. The Laboratory is managed by Princeton University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science, which is the largest single supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Read the abstract here: Comisso, L.; Lingam, M.; Huang, Y.-M.; Bhattacharjee, A. General theory of the plasmoid instability. Physics of Plasmas 23, 2016. DOI: 10.1063/1.4964481

You must be logged in to post a comment.