By Catherine Zandonella, Office of the Dean for Research

Sometimes being too focused on a task is not a good thing.

Sometimes being too focused on a task is not a good thing.

During tasks that require our attention, we might become so engrossed in what we are doing that we fail to notice there is a better way to get the job done.

For example, let’s say you are coming out of a New York City subway one late afternoon and you want to find out which way is west. You might begin to scan street signs and then suddenly realize that you could just look for the setting sun.

A new study explored the question of how the brain switches from an ongoing strategy to a new and perhaps more efficient one. The study, conducted by researchers at Princeton University, Humboldt University of Berlin, the Bernstein Center for Computational Neuroscience in Berlin, and the University of Milan-Bicocca, found that activity in a region of the brain known as the medial prefrontal cortex was involved in monitoring what is happening outside one’s current focus of attention and shifting focus from a successful strategy to one that is even better. They published the finding in the journal Neuron.

“The human brain at any moment in time has to process quite a wealth of information,” said Nicolas Schuck, a postdoctoral research associate in the Princeton Neuroscience Institute and first author on the study. “The brain has evolved mechanisms that filter that information in a way that is useful for the task that you are doing. But the filter has a disadvantage: you might miss out on important information that is outside your current focus.”

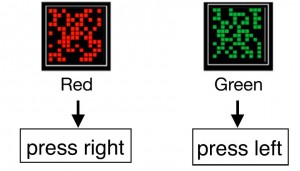

Schuck and his colleagues wanted to study what happens at the moment when people realize there is a different and potentially better way of doing things. They asked volunteers to play a game while their brains were scanned with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The volunteers were instructed to press one of two buttons depending on the location of colored squares on a screen. However, the game contained a hidden pattern that the researchers did not tell the participants about, namely, that if the squares were green, they always appeared in one part of the screen and if the squares were red, they always appeared in another part. The researchers refrained from telling players that they could improve their performance by paying attention to the color instead of the location of the squares.

Not all of the players figured out that there was a more efficient way to play the game. However, among those that did, their brain images revealed specific signals in the medial prefrontal cortex that corresponded to the color of the squares. These signals arose minutes before the participants switched their strategies. This signal was so reliable that the researchers could use it to predict spontaneous strategy shifts ahead of time, Schuck said.

“These findings are important to better understand the role of the medial prefrontal cortex in the cascade of processes leading to the final behavioral change, and more generally, to understand the role of the medial prefrontal cortex in human cognition,” said Carlo Reverberi, a researcher at the University of Milan-Bicocca and senior author on the study. “Our findings suggest that the medial prefrontal cortex is ‘simulating’ in the background an alternative strategy, while the overt behavior is still shaped by the old strategy.”

The study design – specifically, not telling the participants that there was a more effective strategy – enabled the researchers to show that the brain can monitor background information while focused on a task, and choose to act on that background information.

“What was quite special about the study was that the behavior was completely without instruction,” Schuck said. “When the behavior changed, this reflected a spontaneous internal process.”

Before this study, he said, most researchers had focused on the question of switching strategies because you made a mistake or you realized that your current approach isn’t working. “But what we were able to explore,” he said, “is what happens when people switch to a new way of doing things based on information from their surroundings.” In this way, the study sheds light on how learning and attention can interact, he said.

The study has relevance for the question of how the brain balances the need to maintain attention with the need to incorporate new information about the environment, and may eventually help our understanding of disorders that involve attention deficits.

Schuck designed and conducted the experiments while a graduate student at Humboldt University and the International Max Planck Research School on the Life Course (LIFE) together with the other authors, and conducted the analysis at Princeton University in the laboratory of Yael Niv, assistant professor of psychology and the Princeton Neuroscience Institute in close collaboration with Reverberi.

The research was supported through a grant from the U.S. National Institutes of Health, the International Max Planck Research School LIFE, the Italian Ministry of University, the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research, and the German Research Foundation.

Nicolas W. Schuck, Robert Gaschler, Dorit Wenke, Jakob Heinzle, Peter A. Frensch, John-Dylan Haynes, and Carlo Reverberi. Medial Prefrontal Cortex Predicts Internally Driven Strategy Shifts, Neuron (2015) http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2015.03.015.

You must be logged in to post a comment.