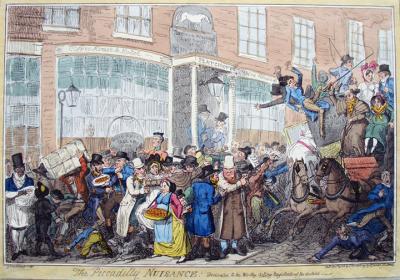

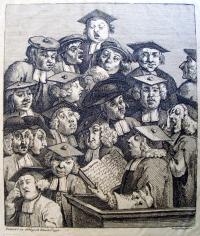

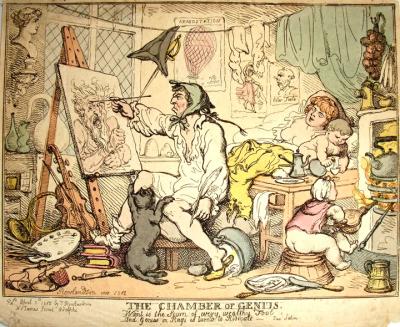

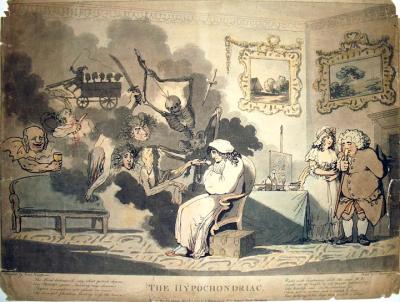

William Hogarth (1697-1764), The Stage-Coach, or The Country Inn Yard, June 1747. Engraving. Graphic Arts Collection Hogarth GC113.

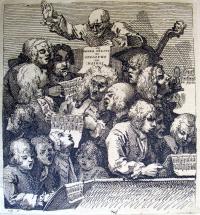

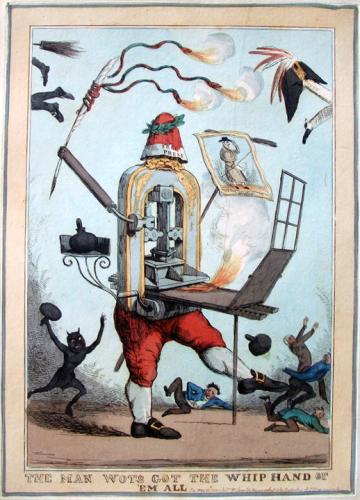

Hogarth’s print, The Stage-Coach, was first advertised on June 26, 1747 as a print representing “a country inn yard at election time.” Since the election had only been announced eight days earlier, Hogarth must have completed the scene with some haste. The only direct reference to the campaign is the crowd in the back, perhaps a comment on the lack of attention the election received from the English people.

The central focus of Hogarth’s print is the woman with her back to us, entering the coach. Ronald Paulson wrote, “whether we think of her as “broadbottom” or as backside, she embodies self-absorption and unawareness of what is going on around her as she prepares to disappear inside the coach. The composition focuses on her back, and creates another verbal pun: she is literally “turning her back” on the urgency of the election… .”

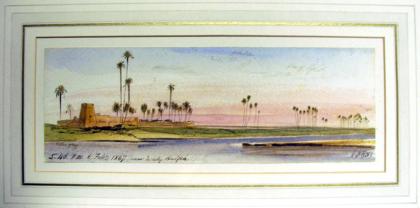

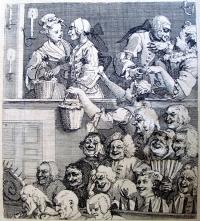

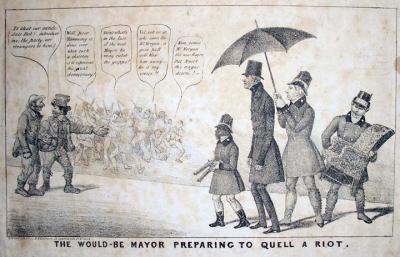

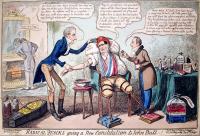

Over seventy years later, George Cruikshank took this image and re-imagined it for contemporary London society. At first only indirectly as The Piccadilly Nuisance, Dedicated to the Worthy Acting Magistrates of the District with the stage coach seen from the side. The followed year, he tried again with Travelling in England, which more directly echoes Hogarth’s print.

George Cruikshank (1792-1878), The Piccadilly Nuisance. Dedicated to the Worthy Acting Magistrates of the District, December 29, 1818. Etching with hand coloring. GC022 Cruikshank Collection. Gift of Richard W. Meirs, Class of 1888.

George Cruikshank (1792-1878), Travelling in England, or A Peep from the White Horse Cellar, August 12, 1819. Etching with hand coloring. GC022 Cruikshank Collection. Gift of Richard W. Meirs, Class of 1888.

Recent Comments